April 19, 1919: Baseball resumes after World War I on Patriots Day in Boston

No matter your perspective, the 1919 Patriots Day opening day doubleheader at Braves Field just didn’t feel the same as those previously played in the twentieth century. Many things swirled in the festive atmosphere that April 19, including the lingering sweet aroma of the January 15 molasses tank explosion/flood tragedy in the North End that killed 21 workers and residents. World War I officially ended five months before (the Treaty of Versailles was not signed until June 1919) but more importantly, the devastating Spanish Flu epidemic was finally beginning to wane in the Hub, once Ground Zero for it. Every day ships entered Boston Harbor with returning troops from Europe, bringing joy and relief to awaiting households, but they docked in the midst of continuing pandemic burials.

No matter your perspective, the 1919 Patriots Day opening day doubleheader at Braves Field just didn’t feel the same as those previously played in the twentieth century. Many things swirled in the festive atmosphere that April 19, including the lingering sweet aroma of the January 15 molasses tank explosion/flood tragedy in the North End that killed 21 workers and residents. World War I officially ended five months before (the Treaty of Versailles was not signed until June 1919) but more importantly, the devastating Spanish Flu epidemic was finally beginning to wane in the Hub, once Ground Zero for it. Every day ships entered Boston Harbor with returning troops from Europe, bringing joy and relief to awaiting households, but they docked in the midst of continuing pandemic burials.

Added to the day’s headline mix was the ongoing New England telephone and telegraph operators strike. That inconvenient chaos was colliding with the traditional Patriots Day (state holiday officially legislated in 1894) celebrations, sandwiched between between solemn Good Friday and Lent-ending Easter.1 Baseball did not take a back-row chair, as there were more than 50 college and high-school games on tap. Dozens of schools vied for attention with various other amateur athletic events including the 22nd Boston Marathon, by then basking in its own national fame.

Baseball normally enjoyed a lofty perch in this carnival of leisure, but in preseason 1919 the moguls were very concerned that fans might still be depressed about the war, the flu carnage, and the shortened 1918 season. They didn’t know how much turnstile enthusiasm to expect. Newly appointed National League President John A. Heydler was there to witness the event at the invitation of George Washington Grant, who had bought the Braves in January.

The NL’s first pitch of 1919 mirrored those tossed in 1897 and 1901, the only opening pitch thrown that day. Baseball’s other combatants, as well as these two teams, would not convene for four more days. Conflicting Boston season openers were in vogue in 1902-03 when the two rival leagues battled over the signing (and stealing) of players. The NL Beaneaters played two games with Brooklyn in 1902 while the upstart American League Bostons hosted Baltimore in a solo tilt. An awkward duel occurred in 1903 when both Boston squads played twin bills with their respective Philadelphia foes. This happened on April 20 because the 19th was a Sunday — no pro ball was allowed.2 A reasonable compromise apparently ended the one-day economic pettiness in 1904 and beyond as the Beaneaters traveled to Brooklyn and the Americans had the city’s cranks all to themselves. After that, the NL Doves/Rustlers/Braves drew the odd years for a lucrative Patriots Day gate and the Americans/Red Sox got the even years.

By 1919 the Braves’ fortunes had fallen from their “Miracle” of 1914 and good times of 1915-16, while the Brooklyn Superbas/Robins/Dodgers’ success had also dropped since their 1916 pennant.3 Meanwhile a mile-plus down Commonwealth Avenue, the Red Sox had captured the 1918 pennant and World Series from the Cubs in the war-curtailed season. Now the Red Sox were also hogging some of April’s sports columns as slugging phenom Babe Ruth hit four straight home runs on Good Friday in an exhibition against Jack Dunn’s International League Orioles in Ruth’s Baltimore hometown. Ruth clouted two more on Saturday, setting Easter’s sports pages ablaze nationwide.

Cavernous Braves Field hosted this combined Patriots Day, Opening Day throng for the first time in 1919. In 1915 the Braves celebrated Patriots Day at Fenway Park by whipping Brooklyn 7-2, 6-4. NL Boston beat Philadelphia 7-3, 4-2 in 1917, but it was not Opening Day; that had come on April 12. Brooklyn was on Boston’s opening menu several times (1890, 1894, and 1919 on Patriots Day), having an overall 4-10 record by day’s end.4

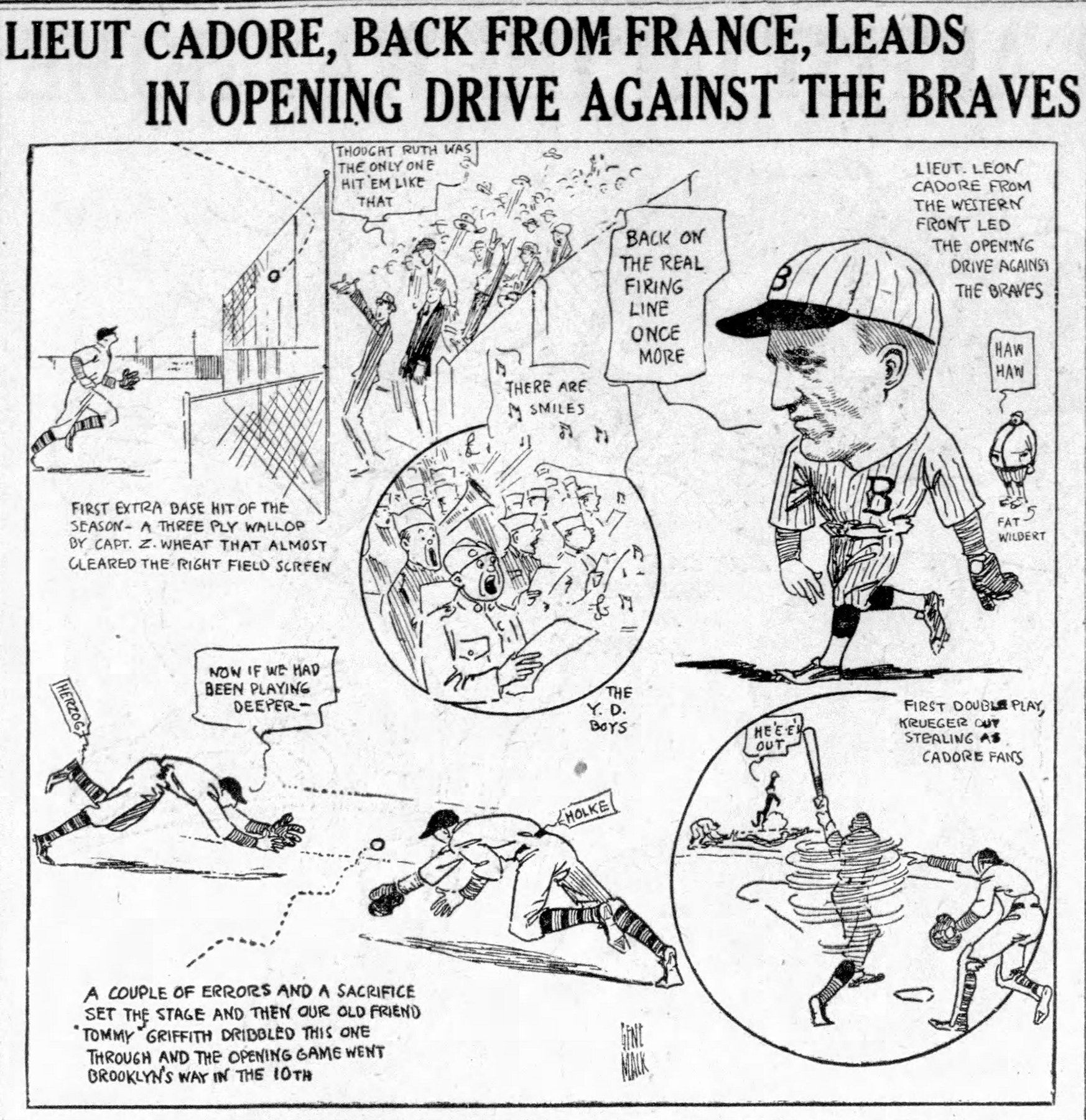

Saturday morning dawned chilly but clear in the Hub. Brooklyn had not faced the Braves since July 2, 1918, and both second-division teams were eager to show improvement. Lt. Leon Cadore, back from rugged Army duty in France, pitched the 10:30 morning game for the visiting Dodgers. He was 2-1 lifetime at Braves Field, really pitching only one season, 1917, recording a 13-13 mark. Cadore’s future baseball fame came a year and two weeks later when he and Joe Oeschger endured a record 26-inning, 1-1 tie in Braves Field. New York native and Miracle Braves ace Dick Rudolph was the host hurler. He dipped to 9-10 in 1918, but was 4-2 at Braves Field in his career against the Superbas. Careerwise, Rudolph was 103-79, Cadore 14-15 as 1919 began.

Six-year Boston manager George Stallings was missing some crucial offense. Baseball’s first World War I enlistee, Hank Gowdy (.279), could not report for action until May 24 (Hank Gowdy Day) and Native American Olympic star Jim Thorpe (.327) would not be traded from New York to the Braves for another month. Walter “Rabbit” Maranville (.267) was only a week back himself from his Navy duties and had practiced just once. He played for his USS Pennsylvania team and while he was in Cuba in March, but was not yet big league-tuned. Through a New York Giants deal, via Cincinnati, newcomer Walter Holke provided some needed punch (.292) along with journeyman Charlie “Buck” Herzog (.280). Reports had the Braves returning from their Georgia training camp in very good condition.5 On the visiting bench, Brooklyn’s five-year field boss Wilbert “Uncle Robbie” Robinson had his veteran roster ready. Zack Wheat’s lethal bat (.297; .335 NL title in 1918) was set, as was his pasture sidekick, Henry “Hi” Myers (.307, NL top 73 RBIs in 1919, 14 triples).6 Ivan “Ivy” Olson (.278, 164 hits in 1919) embarked on his best season. Missing was newly acquired first baseman Ed Konetchy (.298), a Boston contract holdout. His being dealt to Brooklyn was announced in that morning’s papers.

A crisp 50 degrees greeted 4,000 to 8,000 fans (depending on your news source). Respected umpires Bill Klem and Bob Emslie were the Opening Day arbiters. In the first inning, Wheat, newly appointed Superbas captain, wasted no time getting into his dangerous groove. After Lew Malone (Army) singled, Zack stroked a triple knocking home baseball’s first run of the year. Olson singled in the next frame and was brought home by Ernie Krueger’s (Army) safety. Cadore sailed along until the seventh when three Braves singles and Maranville’s sacrifice fly plated the equalizers. With the score still 2-2 in the 10th, Rudolph’s defense went AWOL and Brooklyn executed excellent small-ball strategy. Cadore reached on Maranville’s error and a sacrifice attempt was botched by catcher Art Wilson’s bad throw. Malone’s sacrifice put runners at second and third and newcomer (dealt from Cincinnati) Tommy Griffith singled in both mates. Two batters later, bat-whiz Myers squeezed him home perfectly for a 5-2 lead. Myers’ fine running catch of Joe Riggert’s liner ended the game. Each team made 10 hits but Boston committed five errors and left eight on base.7

Despite his first-game miscues, Maranville was presented with a large floral display from friends of the Morning Glory Club of Charlestown (or his admiring shipmates, depending on which paper you read). Big Jeff Pfeffer (then 79-53) was Brooklyn’s afternoon pitching choice while Stallings dropped his original pick, Art Nehf (44-32), and gave the ball to Don Carlos Pat Ragan (76-102). Like Cadore, Pfeffer had one victory in 1918 as he had enlisted in the Navy.8 The estimated afternoon mob of 20,000 was no big deal to Pfeffer because he had seen 42,600 fans packed into Red Sox-borrowed Braves Field for the Game Five finale of the 1916 World Series, which he lost to Ernie Shore, 4-1. Big game, big stadium, big gate.

Meanwhile Ragan was tossing some of his last pitches of an eight-year career. Things looked bright when he fanned the first two Brooklyn batters and gave up one hit through four innings. However, with two outs in the fifth, Maranville opened the gates again with a bobble on Ollie O’Mara’s bouncer. Krueger followed with the second Brooklyn hit and Pfeffer drove a solid smash to center fielder Riggert, who ran a long way, made a nice grab, but then dropped the sphere, allowing both runners to score (unearned). In Brooklyn’s sixth, Griffith singled, Holke mishandled Wheat’s grounder and the versatile Myers advanced both runners. Olson drove Griffith home with a single off Ragan’s shin (unearned).

Down 3-0, Boston’s Tom Miller (2-for-8 career) pinch-hit for the unlucky Ragan in the seventh and singled. Maranville walked and Charlie Herzog’s safety tallied Miller. Pfeffer came close to blowing his own game in the eighth when he walked Riggert, hit Holke, plunked Joe Kelly, and, after a force out at home, walked rookie pinch-hitter Jack Scott, scoring Holke. Big Jeff then snuffed out the self-inflicted, no-hit rally. After 105 minutes of lackluster play, Braves fans headed home for dinner, their team having lost 3-2. Pfeffer allowed nine hits, while his Superbas got eight. Most of the Robins’ holiday runs were gift-wrapped by nine Boston errors, plus the Braves stranded 20.9

Sources

Information for this essay was compiled mostly through Retrosheet game and player logs, and next-day newspaper accounts of all of the games mentioned from the Boston Globe, Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Brooklyn Daily Times, Brooklyn Citizen, and Brooklyn Standard Union. The A.J. Reach and A.G. Spalding Baseball Guides for 1918 and 1919 were also consulted.

Notes

1 Starting in 1890 the Patriots Day gate was coveted by the “Gay Nineties” Beaneaters and both the Americans and Nationals in the first 1900s decades. Teams that played that day then exited town for warmer venues, returning in milder May. Patriots Day was an intentionally legislated excuse to cast off winter’s chilly misery and commemorate the historic 1775 impromptu skirmishes for colonial independence out at Lexington Green (“Shot heard ’round the world”) and Concord Bridge, 8 and 12 miles to Boston’s northwest. Colonial garb and musket firing were crowd-pleasing staples. Hub clubs could open their season, their home season or just celebrate the holiday on that big gate occasion.

2 According to the April 20, 1903, Boston Globe, crazed crowds totaling 27,600 supported the Americans’ split decision while the Nationals saw 6,500 patrons in the stands for their combined split. The AL’s Huntington Avenue Grounds home plate was about 800 feet from the NL’s venerable South End Grounds revered dish, separated only by myriad railroad tracks and brick walls. It was estimated that 200,000 witnessed parts of the Marathon.

3 Just as the Boston team changed names (Beaneaters, Doves, Rustlers, and Braves) in this era, the Brooklyn squads were called the Robins, Superbas, and Dodgers, depending on which paper you read and when. In 1919 Brooklyn’s four major papers used all three names; the Eagle preferred “Superbas.”

4 In a sidebar story, the Brooklyn Standard Union went so far as to remind fans in the “City of Churches” that their boys played such an April 19 game in Boston when it was welcomed from the American Association into the NL in 1890. Beaten 15-9 at Boston’s magnificent South End Grounds, it was an inauspicious start for the Bridegrooms, who eventually won the NL pennant. The paper’s historians declined to note that on that same day, only 2.5 miles east, the rebel Players’ League Boston Reds defeated the Brooklyn Wonders, 3-2, at the Congress Street Grounds, the “opening game” for each. They finished one-two in that League’s solo season.

5 The Braves’ Columbus, Georgia, training site was 105 miles south of Atlanta along the Chattahoochee River, adjacent to Fort Benning. Braves players were happy that the last two exhibition games were rained out, giving them more time to relax on the train to Boston. On board they encountered at least a dozen war-weary soldiers, most missing limbs. In awe of that sacrifice, the sympathetic ballplayers cheerfully treated the heroes to upgraded food, drink, and cigars along the homebound route.

6 Myers was the player who smacked a first-inning solo inside-the-park home run off Babe Ruth in Game Two of the 1916 World Series. Boston won 2-1 in 14 innings at Braves Field.

7 Biased Boston and skeptical Brooklyn news outlets differed in crowd size estimates. The Boston Globe boasted 10,000 and 20,000 for the two games, several thousand at each game invited veterans. Brooklyn’s four papers varied from 4,000 to 8,000 for the morning contest, and while the Brooklyn Daily Eagle would accept only 12,000 for the afternoon match, the others leaned toward 15,000 to 20,000. In between games the temperature rose to near 60 and Finland native Carl W. Linder of Quincy, a 30-year-old worker at the nearby Fore River shipyard, won the Marathon in 150 minutes. Two other runners of Finnish descent from the field of 47, William Wick (Quincy) and Otto J. Laakso (Brooklyn) were next to cross the line. The Gaffney Street entrance to Braves Field became mobbed by Marathon watchers now wanting some baseball action. The 3:15 start was postponed to 3:45; few fans seemed to mind the delay.

8 Brooklyn’s Opening Day starters Cadore and Pfeffer were among the 103 NLers who served their country during the war. Cadore volunteered for the Army and went to Officer Candidate School in late 1917. He got a furlough in early June 1918 and pitched on June 5 and 8 at Ebbets Field. He shut out St. Louis 2-0 on four hits (Wheat had two RBIs) and then two-hit Pittsburgh over eight innings in a 1-1 tie before being pinch-hit for. (Myers’ RBI in ninth tied it.) The Dodgers won 2-1 in 12 innings (Myers run). Lt. Cadore gained fame in France by commanding a company in the “colored” 369th Infantry Regiment, “the Harlem Hellfighters,” which captured 1,000 German soldiers the day before the Armistice. Pfeffer volunteered for the Navy and trained at the Great Lakes facility, 27 miles north of Chicago. On a weekend pass, he pitched at Cubs Park (Weeghman Field) on July 19, two-hitting the Cubs, 2-0, behind RBIs by Wheat and Myers (Olson both runs). In all Brooklyn had 18 roster players who were drafted or volunteered and Boston had 14.

9 Brooklyn got off to a nice 9-1 start in 1919, behind 4-0 Pfeffer. Boston headed the opposite way, losing its first nine games. In the end Brooklyn was 69-71 and Boston 57-83, both remaining in the second division. The next time the two teams played on Patriots Day at Braves Field was 1929 (doubleheader host sweep, 6-5, 5-1). The teams had opened the season the day before with a 13-12 slugfest win by Boston, which featured solid swatting by George Sisler and Floyd “Babe” Herman.

While most players looked forward to the new campaign free of war and disease worries, poor error-prone infielder Oliver O’Mara’s (.231) four-year, 411-game Brooklyn career abruptly ended with this 1919 season-opening doubleheader. Malone was moved to third base (.204) and then Chuck Ward (.233) tried his skills there. O’Mara (.202) got into Game Four of the 1916 World Series at Braves Field facing Hubert “Dutch” Leonard as a pinch-hitter. He struck out, Brooklyn lost 6-2.

Additional Stats

Brooklyn Robins 5

Boston Braves 2

10 innings

Brooklyn Robins 3

Boston Braves 2

Braves Field

Boston, MA

Box Score + PBP:

Game 1:

Game 2:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.