April 2, 1984: Angels’ Forsch slows down Red Sox in a hurry on Opening Day

When the California Angels captured the American League West championship in 1982 and bolted out to a commanding two-game lead in the best-of-five American League Championship Series against the Milwaukee Brewers, Angels manager Gene Mauch could have been excused for feeling more than a twinge of satisfaction with his team on the brink of appearing in its first World Series. But the fates had other plans: The Brewers regained their footing when the ALCS shifted from Anaheim to County Stadium, and they swept the remaining games to advance to the fall classic. Falling on his sword, Mauch resigned as this latest episode reminded many of the collapse of his 1964 Philadelphia Phillies.

When the California Angels captured the American League West championship in 1982 and bolted out to a commanding two-game lead in the best-of-five American League Championship Series against the Milwaukee Brewers, Angels manager Gene Mauch could have been excused for feeling more than a twinge of satisfaction with his team on the brink of appearing in its first World Series. But the fates had other plans: The Brewers regained their footing when the ALCS shifted from Anaheim to County Stadium, and they swept the remaining games to advance to the fall classic. Falling on his sword, Mauch resigned as this latest episode reminded many of the collapse of his 1964 Philadelphia Phillies.

Smitten again by failure, the Angels followed their playoff swoon by underachieving in 1983 under new manager John McNamara. California appeared to be poised for a repeat of capturing the AL West, and they were only one game off the division lead as late as July 21. But over the next month, the Angels’ deficit had grown to double digits, and the tumble worsened as they fell 15 games off the pace on Labor Day weekend.

Ultimately losing 92 games while posting a mere 70 wins, California found good reason for soul-searching at the conclusion of a dreary campaign. Reliable third baseman Doug DeCinces had a two-month stint on the disabled list, three of the four starting pitchers — Tommy John, Ken Forsch, and Geoff Zahn — were 36 or older, Reggie Jackson seemed to be slowing down as evidenced by his .194 batting average, and center fielder Fred Lynn, still trying to live up to the credentials he established in his days with the Red Sox, had a team-best 74 RBIs, an underwhelmingly modest total. Amazingly, 35-year-old veteran catcher Bob Boone led the team in games played with 142 and batted a respectable .256.

A bit of front-office drama was already in progress during the September debacle: Mauch was named California’s director of player personnel, a move that McNamara found to be disquieting. The Sporting News reported, “At least for now, [Mauch’s] days in uniform are behind him. Now, he is a suit-and-tie man,” and the team was even remodeling an employee lounge into an office for the former skipper.1 Yet, the Angels found it necessary to convene the front-office staff in early October to assure McNamara that his job was safe.

The Angels re-signed their potential free agents, inking DeCinces, Boone, Brian Downing, Ellis Valentine, and Rod Carew to forestall a feared “self-destruction” if so many core players had opted to leave the team.2 For 1984, hope abounded that two key players would be recovered from injuries: DeCinces and shortstop Rick Burleson, who since April 1982 had missed 224 games with rotator cuff problems. The Angels also glimpsed their future with rookie shortstop Dick Schofield awaiting his chance. Lynn was shifted from center field to right in order to make way for another rookie, the fleet-footed Gary Pettis. The team’s overall personnel situation prompted the sage beat writer Peter Gammons to observe that “the Angels are nobody’s patsy.”3

As spring training progressed and veteran players assimilated into the lineup of exhibition games, the status of Burleson became clear in a most unfortunate way. After his fourth appearance, the shortstop was felled by pain in his shoulder, thereby clearing the way for Schofield to step into the void. Meanwhile, Pettis was impressing just as the Angels had hoped, securing his spot by smacking seven hits and scoring as many runs in a pair of games near the end of training camp.

Regardless of expectations, it may be thought that, if anything, there would be less pressure on the Angels entering the 1984 campaign, since the Chicago White Sox were heavy favorites to repeat in the AL West. Gammons opined that other than Chicago, “[t]he injury-prone Angels are the only other [divisional] club capable of winning 90 games — and they’re just as capable of finishing sixth.”4

By Opening Day, McNamara had settled on a mixture of old hands and promising new blood for the season’s debut against the Boston Red Sox. To face Boston’s left-handed starter Bruce Hurst, McNamara pulled a curious switch: The speedy Pettis, who played center and batted leadoff most of the spring, was dropped to ninth, while designated hitter Downing batted leadoff. McNamara defended the change, asserting, “I want to put more pressure on the other team from the beginning,” a move that had a degree of merit given Downing’s proven ability to draw walks and hit for power.5 In the number-two hole was first baseman Carew, followed by left fielder Juan Beniquez, with DeCinces playing third base and batting cleanup. Now in right field, Lynn hit fifth ahead of Bobby Grich, who was at his accustomed place at second base. Grich’s new keystone partner, Schofield, was slotted seventh, Boone hit eighth and was behind the plate, and Pettis roamed center field and anchored the bottom of the order.

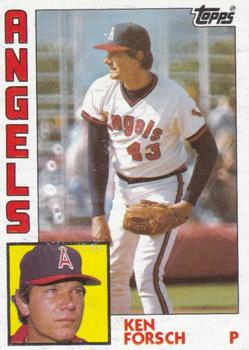

For the visitors, manager Ralph Houk posted a starting lineup of Angels alumnus Jerry Remy at second, Dwight Evans in right, Wade Boggs at third base, left fielder Jim Rice batting cleanup, Mike Easler — another Angel castoff — serving as the DH, Tony Armas manning center field, Rich Gedman the catcher, Dave Stapleton at first base, and shortstop Glenn Hoffman batting ninth. This group would go to the plate against Ken Forsch, one of three 11-game winners on California’s pitching staff the previous year. And for the first time in over two decades, Boston would not have Carl Yastrzemski on the roster, as the venerable old pro began the waiting period for his eventual election to the Baseball Hall of Fame.

When the 7:30 P.M. game commenced, Forsch and Hurst both pitched as if they were going to miss a dinner reservation at the landmark Mr. Stox restaurant, just down the street from Anaheim Stadium. Forsch set the Red Sox down in order in the opening frame, and over the next three innings allowed three harmless singles, to Easler, Remy, and Boggs. Getting Boston three-up-and-three-down in the fifth, sixth, and seventh, Forsch was matched in his stinginess by Hurst, who yielded a single to Carew in the first — and then picked him off — and thereafter retired 11 straight Angels before running into trouble with one out in the bottom of the fifth.

Lynn hit a double, and following a strikeout by Grich, advanced to third on a single by Schofield, but the danger passed when Boone flied out. In the California sixth, Downing drew a one-out walk, went to second on Carew’s second hit, and advanced to third on a fly ball by Beniquez, but DeCinces grounded out to Hurst to end the inning. Grich’s single in the seventh also went by the boards.

With the game scoreless entering the eighth inning, Boston at last drew first blood: Gedman hit a one-out single and was replaced by pinch-runner Reid Nichols, and Stapleton grounded to third base to move Nichols to second. Houk removed Hoffman in favor of Rick Miller, another ex-Angel now in his second tour with the Red Sox, who then doubled home Nichols. When Remy singled to center, Miller was cut down at the plate on a throw by Pettis to avoid further damage. In the bottom half of the frame, Pettis became Hurst’s fourth and final strikeout victim, and Hurst induced both Downing and Carew to ground out.

When Forsch set down all three Red Sox batters in the top of the ninth, it was up to the meat of the California batting order to produce. Hurst surrendered a leadoff base hit to Beniquez, but DeCinces failed to advance him. Hurst walked Lynn, which prompted Houk to bring in Bob Stanley, the Red Sox closer, who saved 33 games in 1983. Stanley got Grich to ground out to third base, but both runners moved up, prompting an intentional walk to pinch-hitter Daryl Sconiers to set up a force play at any base.

This strategy worked in theory when Boone hit a grounder to Jackie Gutierrez, who had taken over at short for Hoffman. But the rookie from Colombia, playing in only his sixth big-league game, threw wildly to first base, enabling Beniquez and Lynn to scoot home with a pair of unearned runs, and the Angels escaped with an ugly win that took only an hour and 54 minutes to complete.

While the Red Sox’ misfortune benefited the Angels, California did not take the opportunity to use Boston’s gift as a true springboard. Over the next week, the Angels lost five of their next six contests — all at home — yet they remained in contention throughout the season, finishing at 81-81, just three games behind the division-winning Kansas City Royals. In the ensuing offseason, managerial “musical chairs” became fashionable: John McNamara was ousted from the Angels and found a new home in Boston, replacing Ralph Houk, while Gene Mauch decamped from his executive suite and again donned a uniform as the Angels’ manager.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Baseball-Reference.com and the 1984 California Angels Media Guide.

https://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/CAL/CAL198404020.shtml

https://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1984/B04020CAL1984.htm

Notes

1 John Strege, “Angels a Bit Hazy in Mauch’s Duties,” The Sporting News, October 3, 1983: 18.

2 John Strege, “Boone Decides to Stay with Angels,” The Sporting News, November 14, 1983: 52.

3 Peter Gammons, “Watch for Chisox-Angels Feud to Erupt,” The Sporting News, January 9, 1984: 34.

4 Peter Gammons, “Orioles, Chisox Have Pitching to Repeat,” The Sporting News, April 2, 1984: 37.

5 McNamara quoted in Tom Singer, “Quiet Schofield Defies His Age,” The Sporting News, April 16, 1984: 15.

Additional Stats

California Angels 2

Boston Red Sox 1

Anaheim Stadium

Anaheim, CA

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.