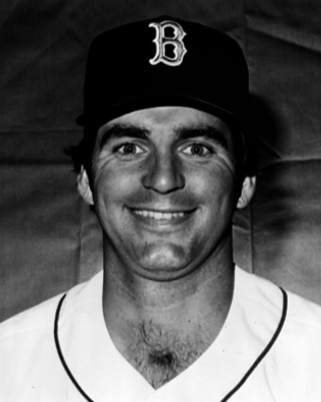

Bruce Hurst

“I loved Fenway. I loved playing there,” said southpaw Bruce Hurst, who hurled for the Boston Red Sox from 1980 to 1988 before signing as a free agent with the San Diego Padres.1 Best known for his command performance in the 1986 World Series against the New York Mets, which included two impressive victories and a Game Seven start on three days’ rest, Hurst was one of the most consistent and underrated pitchers of his era. During a 10-year stretch from 1983 to 1992, he was the only big leaguer to notch at least 10 wins in each season, averaging almost 14 victories and 220 innings per campaign.

“I loved Fenway. I loved playing there,” said southpaw Bruce Hurst, who hurled for the Boston Red Sox from 1980 to 1988 before signing as a free agent with the San Diego Padres.1 Best known for his command performance in the 1986 World Series against the New York Mets, which included two impressive victories and a Game Seven start on three days’ rest, Hurst was one of the most consistent and underrated pitchers of his era. During a 10-year stretch from 1983 to 1992, he was the only big leaguer to notch at least 10 wins in each season, averaging almost 14 victories and 220 innings per campaign.

To understand Bruce Hurst, one needs to know his roots, and they begin in St. George, Utah, a small Mojave Desert town of about 4,000 people in the southwest corner of the state, 120 miles from Las Vegas. Called Dixie by the locals, St. George was founded by Mormon missionaries in the nineteenth century to develop a cotton-farming industry. Mormon culture still permeates the picturesque town, enveloped by jagged rock formations. Bruce Vee Hurst was born there on March 24, 1958, the fifth and final child of John and Beth (Bruhn) Hurst, who divorced when he was 5 years old. Raised in a tight-knit Mormon community, Bruce had plenty of father figures, including his two other brothers, Ross and Buck, and uncles, and a nurturing family. His mother owned and operated the Hurst Variety department store, which provided the family a solid middle-class lifestyle.

Bruce’s adolescent years were filled with sports, fishing, and a fondness for music, but were also marked by an early challenge. By the time he was 2, his legs were so badly bowed that doctors put on plaster casts that eventually corrected the malady. A tall, gangly kid, Bruce played Little League baseball, learned how to throw a curveball, and enjoyed opportunities to travel, but didn’t take the sport too seriously. His favorite pastime was basketball, and as he matured he fancied himself as a future NBA star. Athletics enabled Bruce, a shy, sensitive, and self-conscious youngster, to get out of his shell.

By his teenage years, Bruce began to take baseball more seriously, owing to the tireless and selfless mentoring of Kent Garrett, a former baseball player at Brigham Young University who coached a local team. “For some reason Garrett saw something in me,” Hurst told the author. “He was a stickler for fundamentals and detail. We’d get baseball magazines and cut out pictures of pitchers … and look at the positions they were in. I’d get in front of the three-way mirror and practice my windup. He gave me confidence.” Garrett spent countless hours teaching Bruce the mechanics of pitching. “[Bruce] had the uncanny ability to interpret what you were saying and convert it into what he was doing,” said Garrett.2 Nonetheless, Bruce, who stood 6-foot-3 as a 16-year-old, still dreamed of a basketball career. Called “Rooster” by his teammates at Dixie High School, Bruce led his team to the state tournament in his junior and senior seasons, and overcame a scare – a cracked vertebra – his senior year.

Hurst’s first serious encounter with big-league scouts was after his junior year while participating in an American Legion state tournament. “It all happened really fast, in a year,” said Hurst with an air of incredulity about his rapid and unexpected rise as a serious prospect. “It went from seeing if I was good enough to make a college team to the major-league draft. We weren’t even thinking about the big leagues.” By the end of his prep career he owned a 24-2 record and averaged 14 strikeouts per game as a senior. Hurst admitted that he felt overwhelmed at times by the attention of baseball scouts, scholarships to play college basketball, and a two-year religious mission, a requirement of all Mormons. The Boston Red Sox, on the advice of scout Don Lee, made Hurst the first Utah native chosen in the first round of the baseball draft when they selected him with the 22nd overall pick on June 8, 1976. Several days later Hurst, just weeks removed from graduation, accepted a $50,000 bonus and signed with Boston.

Hurst’s transition to professional baseball was anything but easy. “My insecurities,” he said when asked about his biggest challenge. “I was a small-town boy who had never seen high-caliber baseball before. Now I’m playing against them. I’m a Mormon guy, so the baseball lifestyle was different. The fear of what I’d do in certain situations. That was the way I was raised in the church.” As an 18-year-old with the Elmira Pioneers in the short-season Class-A New York-Pennsylvania League in 1976, he went 3-2 in nine starts and participated in the Florida Instructional League that fall. “Most of the guys couldn’t understand why I didn’t go out and drink with them after games,” said Hurst, who was homesick and concerned about his mother, who lived alone. “That was the first time in my life I had been outside the sheltered Mormon environment.”3 Injuries ended his next two seasons prematurely. He suffered a torn elbow muscle with Winter Haven (Class-A Florida State League) after an impressive start (5-4, 2.08 ERA in 91 innings). Promoted to Bristol in the Double-A Eastern League in 1978, Hurst logged only 33 innings before succumbing to shoulder pain. “I was so worried about hurting my elbow again that I altered my pitching motion.”4 When he left the team to get medical treatment back home in Utah, teammates and the organization wondered if he had quit. In fact, Hurst openly questioned whether a career in baseball was the right career choice for him.

In 1979 Hurst enjoyed a breakout season, going 17-6, splitting his time between Winter Haven and Bristol. More importantly, wrote Boston sportswriter Peter Gammons, “[He] grew out of the head case classification and became the best prospect in the Red Sox organization.”5

“I am amazed that I’m even on the big league roster,” Hurst told Gammons prior to his first spring training, in 1980. “Last spring they had serious reservations about my future.”6 Described as an “early sensation” in camp and touted for his live arm and good control, Hurst jumped from Double-A to prime time, but was rocked in his debut, giving up four hits and five runs in an inning of relief on April 12 against the Brewers in Milwaukee.7 After two rough starts (surrendering nine runs in 3⅔ innings), Hurst was shaky again in his third start (two hits and three runs in the first inning) before firing five no-hit innings to earn his first win on April 26, against the Detroit Tigers.8 With 27 earned runs in 23 innings, it was no surprise when Hurst was optioned to Triple-A Pawtucket on May 14.

Recalled in September, Hurst had a confidence-destroying encounter with his gruff manager, Don Zimmer, notoriously hard on pitchers, “Go home and grow up,” said Zimmer, when he grabbed the ball from Hurst in a first-inning meltdown in a relief outing against Baltimore on September 23. “I was lost and confused,” recounted Hurst in his 1986 biography, Flood Street to Fenway. The Bruce Hurst Story, written by Lyman Hafen.9 The headline-grabbing episode contributed to the perception that Boston had wasted its first-round pick on Hurst.

“I honestly didn’t know if my stuff was good enough to play in the big leagues and the episode with Zim didn’t help,” said Hurst candidly. Assigned to Pawtucket to start the 1981 season, Hurst abruptly jumped the team on May 2. “I wasn’t enjoying the game anymore,” he said. “I couldn’t see any reason to stay.”10 Three days later, he returned, tied lefty Bob Ojeda for the team lead with 12 wins, and posted a robust 2.87 ERA in 157 innings.11 Called up to Boston in September, Hurst made five starts, winning two of them.

In 1982 Hurst overcame a seriously sprained rib-cage muscle in spring training to earn a spot on Boston’s staff and remained with the team the entire season. He made 19 starts, but was plagued by elbow pain most of the season and underwent surgery in the offseason to remove bone chips. Though Hurst’s numbers were unimpressive (3-7, 5.77 ERA in 117 innings), Peter Gammons recognized the southpaw’s potential: “[Hurst’s] curveball, fastball and change-up constitute the best combination of pitches on the staff.”12

Described by Red Sox beat writer Joe Giuliotti as “the best pitcher on the staff most of the year” in 1983, Hurst enjoyed a breakout season, going 12-12, logging 211⅓ innings and posting a 4.09 ERA for a sixth-place club.13 Pain-free, he made 32 starts (completing six of them) and tossed his first two big-league shutouts. Asked what contributed to his success, Hurst replied unequivocally, “Houk and Roarke.” Hurst credited Ralph Houk, Boston’s skipper from 1981 to 1984, for giving him confidence and a chance to learn to pitch. “Mike Roarke, my pitching coach in Pawtucket, had a profound impact on my career and helped with my delivery,” said Hurst. “[Hurst] was more compact with his delivery and seemed to have much better command with his pitches,” said Houk. “He used to pitch with his arms flailing and his high leg kick.”14

Fenway Park can be a nightmare for left-handed pitchers. With the Green Monster looming just about 315 feet away in left field, right-handed batters salivate when a southpaw is on the mound. “I’ll be honest with you, Fenway was intimidating, the size, the history, the fans and their intensity,” responded Hurst when asked about pitching in the historic park. A cerebral and reflective player, Hurst learned to adjust. “It didn’t take me long to realize that Fenway giveth and taketh away,” he continued. “There were cheap balls that went out, but there were some rockets that were singles. I knew I was going to give up a lot of hits in that ballpark, but I also knew that I had places to pitch to – a big right-center field, a big right field. I had to use that to my advantage. I had to learn to make guys hit the other way.” During his nine years as a member of the Red Sox, Hurst won 57 games at Fenway Park, a total that trails only Mel Parnell’s 71 (1947-1956), and exceeds Lefty Grove’s 55 (1934-1941) and Jon Lester’s 51 (2006-2014). With a chuckle, Hurst was quick to point out he enjoyed an advantage Lester didn’t. “Back then, they didn’t block out the center-field bleachers [at Fenway Park]. My curve came out of those white shirts and a lot of guys complained.”

Named Opening Day starter in 1984, Hurst got off to a strong start, completing eight of his first 13 starts with a sparkling 1.98 ERA in 95⅔ innings. Gammons opined that Hurst might “have the best curveball in the American League.”15 After tossing 382 pitches over a three-start stretch in June, he missed 12 days with tightness in his arm. Eventually he developed back spasms which worsened as the season progressed, and landed in traction.16 Hurst improved his record to 10-5 with a complete-game victory over the California Angels on July 21, but was running on fumes. He struggled in his last 13 starts (6.50 ERA in 72 innings) to finish a once-promising campaign with another 12-12 record, while pacing the team in starts (33) and innings (218).

Hurst’s season-ending struggles from the previous campaign continued in 1985. By the end of May he was 1-4 with a 6.36 ERA and soon lost his spot in the rotation. The Boston media and fans, as well as the Red Sox front office, vented their frustration over an underachieving club at Hurst. “[Hurst’s] actions off the field have contributed to the milque toast image,” wrote Dan Shaughnessy.17 He was described as an enigma, mystery, different, fragile, and not tough enough to be a front-end starter.18 “The press labeled me as too shy, too timid, too Mormon,” said Hurst matter-of-factly. “There’s a competitive part of me and I’ve always had an edge. I knew I was insecure and unsure, but I was not timid.” He demanded a trade, and Boston openly shopped him. Defying expectations, Hurst tuned his season around. From June 28 through the end of the season, he was a completely different pitcher. He won 9 of 15 decisions and suddenly transformed into a strikeout pitcher, whiffing 10 or more batters for the first five times of his career. He established a new Red Sox record for lefties with 189 strikeouts to go along with his 11 wins (13 losses) and logged 229⅓ innings.

Hurst had a clear explanation for his success. “I had learned a straight change from Johnny Podres, one of my pitching coaches in the minor leagues, but I lost my feel for it in the big leagues,” he explained to the author. “I knew I needed another pitch, something soft. Everybody was talking about the forkball at that time.” Roger Craig, pitching coach for the Detroit Tigers (1980-1984), helped revive the pitch, most often associated with relievers Elroy Face and Lindy McDaniel of the 1950s and 1960s. Starters Jack Morris of the Tigers and Mike Boddicker of the Baltimore Orioles were successful practitioners of the pitch in the early 1980s. “Craig showed me the grip one day at Fenway in ’84 and I also talked to Bods about it,” said Hurst. “I started to throw it ’85, but I didn’t want to give up on my changeup. I was stuck between the two. About halfway through the year I decided to go for it.”

Hurst explained that a new mental approach to the game accompanied his trust in his forkball. He recalled a game against the Brewers (July 3, 1985), when leadoff hitter Paul Molitor nonchalantly reached out over the plate and casually fouled off a pitch. “That guy had no fear of me. I thought he could do whatever he wants. I said, ‘No more. That’s it.’ And I threw a fastball up and in [and struck him out]. That was the point that turned me from a 12-12, really unsure pitcher to a much better big-league pitcher.” Hurst shut out the Brewers on five hits and registered 10 strikeouts in that career-altering game.

With new-found sense of self-confidence, Hurst got off to a strong start in 1986. He whiffed at least 10 in four of his first nine starts, including 11 in a career-long 10-inning complete-game victory, and a career-high 14 in a complete-game loss in consecutive starts. On May 31 he heard something pop while pushing off the mound and landed awkwardly. Carried off the field, Hurst, who was leading the AL in strikeouts at the time (89), was diagnosed with a severely pulled groin muscle and missed seven weeks. Sportswriter Moss Klein’s prediction that Hurst “can’t be expected to be at top form” once he returned appeared accurate as the southpaw was pummeled in his two starts in July while Boston’s eight-game lead in the AL East had dwindled to just three.19 Proving his critics wrong and that he was a big-game hurler, Hurst won a team-high eight times in August-September, and posted a 2.66 ERA in his final 12 starts of the season. Hurst (13-8, 2.99 ERA in 174⅓ innings), Roger Clemens (24-4, 2.48 ERA), and Dennis “Oil Can” Boyd (16-10, 3.78 ERA) propelled Boston to its first division crown since 1975.

The ever modest Hurst was quick to give credit to his teammates for his success and maturity. “Clemens was the epitome of teammate. We talked a lot about pitching. And Oil Can Boyd, too,” he said. “In 1986 we had Tom Seaver, and it was like the University of Seaver. [Pitching coach] Bill Fischer kept me on task.” Mentioning players – catcher Rich Gedman, second baseman Marty Barrett, and outfielder Dwight Evans, among others, Hurst said, “I saw what it looked like to be a pro and tried to emulate them on the pitching side.”

The Red Sox march to the World Series appeared derailed in the ALCS against the California Angels. Down three games to one (Hurst tossed a complete game to win Game Two), Boston won three consecutive games to advance to the fall classic to face the seemingly invincible and heavily favored New York Mets, winners of 108 games. Given that Clemens had started the final game against the Angels, skipper John McNamara chose Hurst to start Game One. “I prepared the same way, but I was keenly aware that it was the World Series,” said Hurst. “It was crazy at Shea. I knew what to expect from the fans and how they react. Once I took my first warm-up toss, I looked around at my infield. ‘Hey, these are my boys. Let’s go to work.’ It felt so comfortable. You just create the environment in your mind.” Hurstie, as his teammates called him, tossed eight scoreless innings, yielding just four hits to win the game. In Game Five he outdueled Dwight Gooden, hurling a complete-game 10-hitter to push the Red Sox to within one game of their first championship since 1918. “We were not overly excited,” said Hurst about the mood in the clubhouse after his victory. “We knew that things could change on a dime after our experiences in the playoffs against California. After we lost Game Six, we all said we now know how the Angels felt.”

“I wasn’t surprised about getting the start in Game Seven,” said Hurst. “Actually, I was ready for it.” His teammate, Oil Can Boyd, who had been pummeled in Game Three, was livid and charged his skipper and the entire Red Sox organization with racism for skipping him. “Dennis’s reaction still bothers me today,” said Hurst honestly. “In a roundabout way, it didn’t show a lot of confidence in me.” Hurst tossed five scoreless innings, before yielding three runs in the sixth and leaving with the game tied, 3-3. The Mets tacked on three more runs in the seventh off reliever Calvin Schiraldi en route to the championship. Years later McNamara, widely panned for going to Schiraldi, who picked up a record-setting third loss in the series, confirmed reports that Boyd was too drunk to pitch in relief in Game Seven.20

While Boston slumped to a fifth-place finish in 1987, Hurst picked up where he left off in the postseason. Named to his first and only All-Star squad (he did not play), Hurst possessed a stellar record (14-6) in mid-August before a severe virus (typically reported as mononucleosis) sapped his energy. He lost seven of his last eight starts to finish with a 15-13 record and set career highs with 15 complete games and 190 strikeouts.

With his free agency looming in the offseason, Hurst celebrated his 30th birthday in March 1988 by winning a career-best 18 games and finishing fifth in the Cy Young Award balloting. He was named AL pitcher of the month in August when he won five consecutive starts (and extended his personal winning streak to a career-best seven). Included were a 10-inning shutout and an 11-strikeout performance which pushed him over the 1,000 mark in career whiffs, only the third Red Sox player to reach the milestone.21

Despite personal milestones or accolades (he was named the Red Sox player of the year by Boston chapter of the Baseball Writers Association of America), Hurst’s season was anything but enjoyable. “I was an emotional wreck during free agency,” he explained. “I didn’t want to negotiate publicly. I told my agent [Nick Lampros], ‘Let’s go and hammer this out quickly during the season.’ But collusion was going on. It turned into a media circus in Boston and became everything I didn’t want it to become.” When the two sides could not agree on terms early in the season, Boston GM Lou Gorman played hardball and suggested that Hurst test the market. “I felt challenged [by Boston] and never felt their [negotiations] were authentic.”

One of the most sought-after free-agent pitchers, Hurst was wooed by a dozen teams. He ultimately signed a three-year deal with the San Diego Padres, crediting team president Dick Freeman’s honestly and integrity as a deciding factor. More than 25 years after that decision, Hurst took a serious tone when talking about the fateful night when he accepted the Padres’ offer. “I remember hanging up the phone and just sobbing,” he said solemnly. “I thought, ‘What have I done to all the people I care about, that I’d been in the trenches with, and that had been so important to me?’ And now I’m going to a new place. It was a weird feeling. It was not what I had intended to do.”

Hurst made a seamless transition to the National League and San Diego, where the sports media and the fans were much less rabid. “I’m not a savior,” he said in words typical of his team-first attitude. “I just want to be a cog in the machine.”22 In his first four seasons (1989-1992) with the Padres, Hurst continued his solid, consistent performances, posting records of 15-11, 11-9, 15-8, and 14-9 while averaging 227 innings for middle-of-pack teams (save for the second-place finish in 1989). En route to a career-high 244⅔ innings in 1989, Hurst enjoyed revenge of sorts when he tossed one of his NL-high 10 complete games to defeat the Mets on August 17 at Shea Stadium to notch his 100th career victory. “Back in the early ’80s,” he said, “there weren’t many people in Boston who expected me to do it. Maybe in slow-pitch softball.”23 The following season he tied for the NL lead with four shutouts and tossed a career-best 27⅓ consecutive scoreless innings.

After battling a number of injuries in 17 years in professional baseball, Hurst saw his career derailed by a torn rotator cuff suffered near the end of the 1992 season. “I started to feel the injury after a start in St. Louis,” he said. “The next day we were in Chicago and I could not even pull out my golf clubs from my bag.” He underwent surgery in the offseason, but made only 13 more starts in his career. He had a brief stint with the Colorado Rockies in 1993 and signed with the Texas Rangers as a free agent in 1994. “I had a few good games [with Texas], but I knew I was never going to be what I was before, said Hurst. “Maybe a fourth or fifth starter and squeeze out a few more years. But quite honestly, I didn’t know what I was going through.” On June 19, 1994, he announced his retirement, bringing an end to a 15-year big-league career during which he compiled a 145-113 record and posted a 3.92 ERA in 2,417⅓ innings.

Called “crafty” by Vin Scully, “marvelous” by Sparky Anderson, and a “deceptively good pitcher” by Lou Piniella, Hurst developed into a master tactician during his career.24 “I think pitching is a lost art. In today’s world we only see things in relation to the radar gun,” he said. “Young guys never learn pitch sequencing, separation of speeds, and location. I wasn’t overpowering, but wasn’t soft either. In hindsight, I probably would use my fastball more often. I had a really good hook, then my split-finger change became a really good pitch. Learning how to command those pitches and add and subtract speed and [alter] location helped me. I also learned how to expand the strike zone.” Hurst also transformed into an unlikely strikeout pitcher, whiffing 10 or more in a game 17 times and twice ranking second in the AL in strikeouts per nine innings (1985-1986). “Pitching is a lot of psychology,” he said. “I learned how to create doubt in the batters.”

After retiring from baseball, the 36-year-old Hurst settled in Utah with his wife, Holly (née Barton), whom he had met in 1979 while studying at Dixie College in St. George. They married in 1981 and raised four children. Hurst wanted to remain connected to baseball; however, experiences coaching at the college level and with an independent team left him unfulfilled. “I wasn’t interested in going to an organization and climbing through the minor leagues,” he explained. In the late 1990s Hurst found the perfect fit when he accepted an offer to coach at a Major League Baseball Academy in Italy, as part of MLB’s attempt to grow the sport internationally. His involvement in the Major League Academies throughout Europe for a dozen years led to additional opportunities to coach internationally, and serve as a tireless advocate of the sport. He served as pitching coach for the Chinese national baseball team in 2005-2006 and again in 2012-13. Praised for his keen evaluation of talent, Hurst also maintained a close connection to big-league ball in the US. Inducted into the Boston Red Sox Hall of Fame in 2004, Hurst served as special assistant for player development for the Red Sox in 2008. In 2015 he worked in the international office for the Los Angeles Dodgers evaluating talent in Latin and South America. When he along with approximately 40 others were let go in the club’s massive reorganization of its baseball operations in August of that same year, Hurst seemed fed up. “I think I’m kind of done with baseball,” he told Dan Shaughnessy of the Boston Globe.25 As of 2015 Hurst resided with his wife in Phoenix.

Last revised: December 1, 2016

This article originally appeared in “The 1986 Boston Red Sox: There Was More Than Game Six” (SABR, 2016), edited by Bill Nowlin and Leslie Heaphy.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the notes, the author consulted:

Baseball-Reference.com

Retrosheet.org

SABR.org

Author’s interview with Bruce Hurst on January 29, 2015.

Notes

1 The author expresses his sincere appreciate to Bruce Hurst, whom he interviewed on January 29, 2015. All quotations from Hurst are from this interview unless otherwise noted.

2 Lyman Hafen, Flood Street to Fenway. The Bruce Hurst Story. (St. George, Utah: Publishers Palace, 1987), 26.

3 Hafen, 48.

4 Hafen, 56.

5 Peter Gammons, “On Baseball. A lefthanded longshot comes of age,” Boston Globe, December 21, 1979.

6 Ibid.

7 The Sporting News, March 29, 1980, 40.

8 “Pudge (catcher Carlton Fisk), I can’t say enough about him. He came to the mound and kept on me, especially after that rough first inning,” AP, “Rookie Bruce Hurst wins first game for Red Sox,” Tuscaloosa (Alabama) News, April 27, 1980, 4B.

9 Hafen, 64

10 Hafen, 98

11 On April 18, 1981, Hurst was involved in the longest professional baseball game. The Pawtucket Red Sox battled the Rochester Red Wings for 32 innings when the game was suspended with the score tied, 2-2. The seventh of eighth Pawtucket pitchers, Hurst tossed five scoreless innings. The game was resumed on June 23, and the Red Sox scored a run in the 33rd inning to win, 3-2.

12 The Sporting News, December 12, 1982, 44.

13 The Sporting News, September 12, 1983, 16.

14 The Sporting News, April 18, 1983, 23.

15 The Sporting News, May 21, 1984, 16.

16 The Sporting News, July 2, 1984, 16.

17 Dan Shaughnessy, “On Baseball. Bad Raps on a Good Guy,” Boston Globe, March 4, 1986, 65.

18 Alan Greenwood, “Fans See Worst in Sox Hurst,” The Telegraph (Nashua, New Hampshire), June 26, 1985, 15; Bill Reynolds, “A great enigma, a mystery – and, now a winner,” Providence (Rhode Island) Journal, July 5, 1985.

19 The Sporting News, July 28, 1986, 26.

20 Tyler Kepner, “For McNamara, A Final Out That Wasn’t Meant To Be,” New York Times, November 7, 2011.

21 The other two are Cy Young (1,341) and Luis Tiant (1,075).

22 The Sporting News, December 19, 1988, 51.

23 The Sporting News, September 4, 1989, 23.

24 Lee Benson, “Bruce Hurst. The seesaw road from St. George to Boston,” The Deseret News (Salt Lake City, Utah), October 21, 1986.

25 Dan Shaughnessy, “Catching up with Bruce Hurst, the Series MVP who wasn’t,” Boston Globe, December 1, 2015.

Full Name

Bruce Vee Hurst

Born

March 24, 1958 at St. George, UT (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.