April 23, 1914: Chicago Feds open Weeghman Park, later known as Wrigley Field

The Federal League Kansas City Packers and Chicago Chi-Feds played the first game ever at Weeghman Park on April 23, 1914, to an overflow crowd of 21,000, much fanfare, and chilly weather. “Chicago took the Federal League to its bosom yesterday,” wrote Sam Weller in the Chicago Tribune, “and claimed it as a mother would claim a long lost child.”1 The ballpark’s capacity was 18,000, but Weller estimated that 3,000 more fans were standing in the back of the grandstand or on the field. Thousands more had to be turned away, but many took residence in windows and on roofs of nearby buildings.2

The Federal League Kansas City Packers and Chicago Chi-Feds played the first game ever at Weeghman Park on April 23, 1914, to an overflow crowd of 21,000, much fanfare, and chilly weather. “Chicago took the Federal League to its bosom yesterday,” wrote Sam Weller in the Chicago Tribune, “and claimed it as a mother would claim a long lost child.”1 The ballpark’s capacity was 18,000, but Weller estimated that 3,000 more fans were standing in the back of the grandstand or on the field. Thousands more had to be turned away, but many took residence in windows and on roofs of nearby buildings.2

“Owners [Charles] Weeghman and [William] Walker of the north side club and President [James] Gilmore of the new league were so overjoyed with the spectacle that they almost wept,” Weller wrote, “and there is little doubt that it was an epochal day in the history of the national game.”3 Weeghman realized early on that his venue wouldn’t be big enough to accommodate the massive crowd, but longtime business manager Charles Williams, who spent 25 years in the Cubs front office, had everything working beautifully, “just as if the whole thing had been rehearsed.”4

All were met by a cold wind blowing in off Lake Michigan, but that didn’t temper the enthusiasm or pomp that followed. More than a thousand members of the North Side Boosters’ Club held a parade; the Bravo El Toro Club attempted to stage a bullfight on the field, but the bull refused to cooperate; members of the Ladies of the Grand Army of the Republic marched around the field with an American flag led by a band while players from both teams followed behind.5

Chi-Feds manager Joe Tinker, who served as the Cubs’ shortstop from 1902 to 1913 and would again briefly in 1916; his wife; and Weeghman were all presented flowers, and the latter was also given a silver loving cup. Corporation Counsel William H. Sexton threw out the first pitch in Mayor Carter H. Harrison’s absence and the game began.6

Taking the mound for the visitors was George Howard “Chief” Johnson, a Native American born on the Winnebago Reservation in Nebraska who attended the Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania with Jim Thorpe, arguably the world’s greatest athlete at the time and a future major leaguer himself. Johnson began his career in the Class-A Western League in 1909 and pitched there until 1912, mostly with the St. Joseph Drummers, for whom he went 56-39 from 1910 to 1912.

Johnson’s 23-10 showing in 1912 caught the attention of the Chicago White Sox, who purchased his contract only to release him before Opening Day 1913, allegedly because White Sox skipper Nixey Callahan learned that Johnson was a Winnebago and members of that tribe were blacklisted because of their supposed affinity for alcohol.7

The Cincinnati Reds cared nothing for that rumor and signed Johnson. He made his major-league debut on April 16, 1913, against the St. Louis Cardinals and tossed seven shutout innings to earn his first win. Johnson went on to pace the Reds in almost every pitching category, including wins with 14. The New York Times described him as “fat” and “wooden,” but one who could “deal out ciphers with as much success as the more illustrious [Walter] Johnson of Washington.”8

The following season, 1914, Johnson made a start for Cincinnati on April 18 and lasted only four innings in an 8-5 loss to Pittsburgh. Then he jumped to the Kansas City Packers of the Federal League for a reported $3,000 bonus and $5,000 salary.9 When Johnson took the mound against the Chi-Feds on April 23, 1914, he did so despite an injunction issued by Judge Charles M. Foell that barred him from pitching for Kansas City.10

The Packers would have been better off had they obeyed the injunction as Johnson proved ineffective through two innings of work before he was served with papers and removed from the game. After setting Chicago down in the first, Johnson ran into trouble in the second. Center fielder Dutch Zwilling hit a double into the crowd, right fielder Al Wickland advanced Zwilling to third on a bounder in front of the plate, and second baseman Jack Farrell plated the first run of the game with a single to left. Catcher Art Wilson knocked in two more runs with a home run over the left-field wall and Chicago was out to a 3-0 lead.

In two innings of work Johnson allowed three runs on five hits and a walk while fanning one.11 Fellow Nebraska native Dwight Stone took the hill for the Packers in the third and issued a walk to Tinker and a single to first baseman Fred Beck. Zwilling poled another double to score the fourth run of the game and send Beck to third, but Stone escaped without further damage when Beck and Zwilling were both thrown out at the plate on subsequent plays.

The Chi-Feds struck again in the fourth when Wilson belted his second homer of the game, this one clearing the scoreboard in left and landing on Waveland Avenue. Max Flack slapped a one-out double into the crowd and Tinker followed a free pass to Rollie Zeider with a base hit that plated Flack to push the score to 6-0.

Then they added two more tallies in the sixth when Wilson drew a one-out walk, moved to second on pitcher Claude Hendrix’s single, and advanced to third on second baseman Duke Kenworthy’s error on a Flack grounder that filled the bases. Zeider drove in Wilson and Hendrix with a single to increase Chicago’s lead to 8-0, but Flack was caught in a rundown and Tinker grounded out to end the inning.

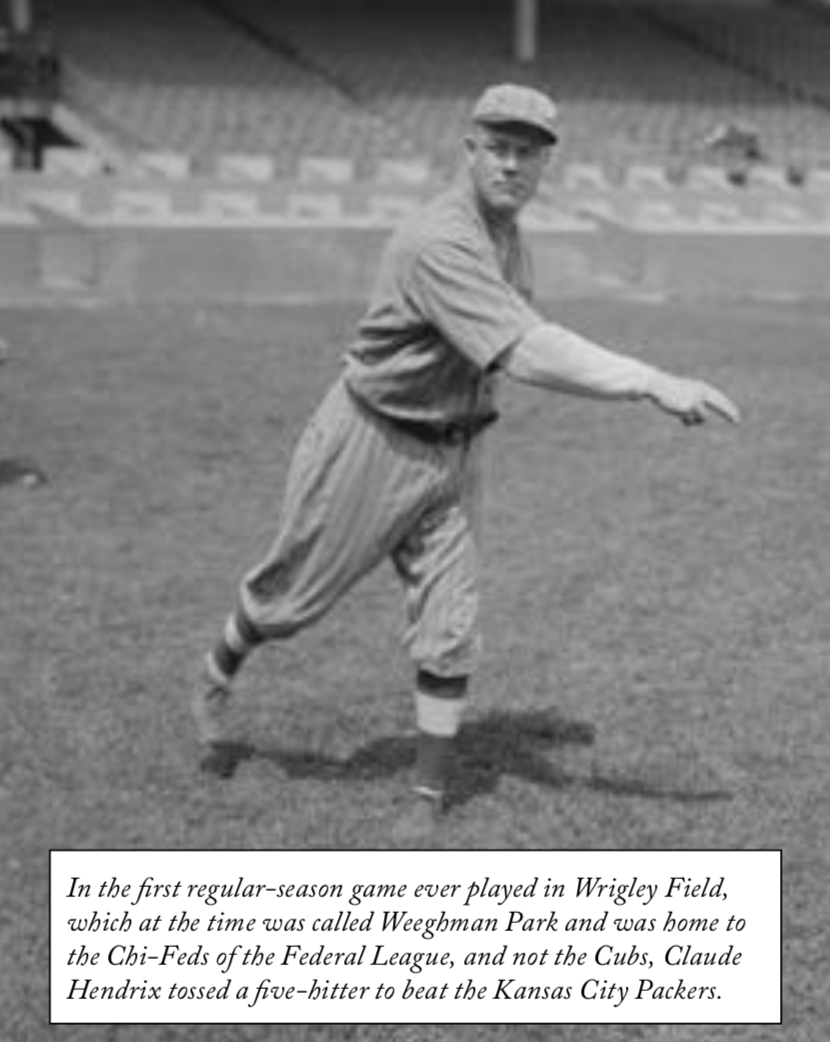

Meanwhile Hendrix, a 6-foot-tall spitball artist from Kansas, who made his major-league debut with the Pirates in 1911, then won 24 games for them in his sophomore season, was mowing down Kansas City batters with relative ease. Weller wrote that Hendrix “simply breezed through the combat without being in danger at any time.”12 Indeed, Hendrix surrendered only two hits through seven innings before allowing his only run in the eighth.

With an eight-run lead in the eighth Hendrix either got careless or started grooving pitches to try to put a quick end to the game. Catcher Ted Easterly led off the frame with a home run to left, and pinch-hitter Grover Gilmore and right fielder John Potts both singled. But a double play erased the threat and Hendrix was off the hook with only one run on his ledger.

Not to be outdone, the Chi-Feds added one more run to their total in the bottom of the eighth on a potentially dangerous play. Farrell singled, advanced to second on an out, and went to third on a passed ball. With Hendrix, a solid hitter, at the plate, Farrell broke for home in an attempted steal. Hendrix didn’t know it was coming and swung at the pitch. “Johnny tried to steal home, but just when he was about to hit the dirt Hendrix singled to center, so Johnny came in straight up,” wrote Weller.13

Hendrix was forced at second and Zeider tapped back to pitcher George Hogan to end the inning, then Hendrix shut the Packers down in the ninth to seal an easy 9-1 victory.

Postscript

Because of numerous injunctions in 1914, Chief Johnson didn’t start pitching regularly for Kansas City until late July. He went 9-10 with a 3.26 ERA and followed that up with a 17-17 showing in 1915 and a 2.75 ERA. He spent another three years in the Pacific Coast League before calling it a career. Concerns about alcoholism proved to be founded as he had several run-ins with the law and abandoned his wife. On June 12, a “drunk and belligerent” Johnson was shot to death in Des Moines, Iowa, over a gambling dispute.14 He was 36.

This article appears in “Wrigley Field: The Friendly Confines at Clark and Addison” (SABR, 2019), edited by Gregory H. Wolf. To read more stories from this book online, click here.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also accessed Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, and SABR.org.

Notes

1 Sam Weller, “Chicago Welcomes Feds, Who Triumph Over Packers, 9-1,” Chicago Tribune, April 24, 1914: 15.

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid.

5 Ibid.

6 Ibid.

7 Thom Karmik, “ ‘Chief’ Johnson and the ‘Winnebago Ban,’” baseballhistorydaily.com/2012/08/23/chief-johnson-and-the-winnebago-ban/, accessed June 11, 2017.

8 “Giants Picked Off Bases in Fast Plays,” New York Times, May 9, 1913: 9.

9 Thom Karmik, “More ‘Chief’ Johnson,” baseballhistorydaily.com/tag/george-johnson/, accessed June 11, 2017.

10 “Packers Lose Johnson,” Ottawa (Kansas) Daily Republic, April 24, 1914: 6.

11 Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org have Johnson allowing four runs, but based on newspaper reports, that’s impossible. Every report found had him being served papers and removed from the game before the third inning, at which time the Chi-Feds had three runs. They scored their fourth run in the third, but Sam Weller of the Chicago Tribune has Dwight Stone starting the third inning and allowing the fourth run, not Johnson. His account includes a play-by-play of every run scored and I have every reason to believe it’s accurate.

12 Weller, “Chicago Welcomes Feds, Who Triumph Over Packers, 9-1,” Chicago Tribune, April 24, 1914: 16.

13 Ibid.

14 “Grand Jury to Probe Death of Chief Johnson,” Des Moines Register, June 16, 1922: 3.

Additional Stats

Chicago Chi-Feds 9

Kansas City Packers 1

Weeghman Park

Chicago, IL

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.