April 29, 1934: Sunday professional baseball comes to Pittsburgh

In 1794, the legislature of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania codified a portion of English common law governing observance of the Christian Sabbath, or day of rest. The laws, known as “blue laws,”1 criminalized “any worldly employment or business whatsoever on Sunday (works of necessity, charity, or wholesome recreation excepted.)”2

In 1794, the legislature of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania codified a portion of English common law governing observance of the Christian Sabbath, or day of rest. The laws, known as “blue laws,”1 criminalized “any worldly employment or business whatsoever on Sunday (works of necessity, charity, or wholesome recreation excepted.)”2

Those laws were still very much in effect and being enforced when the Sesqui-Centennial International Exposition celebrating the 150th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence opened on May 31, 1926, in Philadelphia. Emboldened by the fact that the Exposition operated on Sundays with an admission fee, the Philadelphia Athletics sought and obtained an 11th-hour injunction permitting the club to play a paid-admission Sunday home game on August 22, 1926.3

Although the Pennsylvania Supreme Court ruled the following year that the injunction had been improperly issued and held the blue laws still applicable to Sunday baseball,4 the economic pressures of the Depression continued to spur executives of Pennsylvania’s three professional baseball teams to push to legalizing Sunday games through legislation. By late April 1933, they realized success when Governor Gifford Pinchot signed the Schwartz Bill, which “revised the 1794 Blue Laws and made it possible for every city, borough, and township in the state to decide for itself whether it desired baseball and football between 2 p.m. and 6 p.m. Sunday afternoons, effective in 1934.”5

The Schwarz Bill required local referendums on the issue across the state in the next general election on November 7, 1933. On Election Day, Pittsburgh and Philadelphia overwhelmingly voted for Sunday baseball and football.6

Because the Pirates opened the 1934 season at St. Louis on Tuesday, April 17, and the club didn’t return to Pittsburgh for the home opener until the following Tuesday, the quirks of the schedule gave the distinction of the first legally-authorized regular season7 Sunday home game in Pennsylvania to the A’s on April 22.8 But on the other side of the state, the fervor wasn’t dampened: “Next Sunday, April 29, will be a momentous day for the baseball loving fans of Western Pennsylvania for on that day the Pittsburgh Pirates will meet the rejuvenated Cincinnati Reds in the first Sunday professional ball game in the history of Pittsburgh.”9

Twelve days into the new season, Pirate manager George Gibson had the team at 4-4 after guiding the Bucs to a second-place NL finish, five games behind the Giants, in 1933. The visiting Reds needed rejuvenation—they’d finished in the 1933 cellar but had a new player-manager, catcher Bob O’Farrell. They were 3-6 and riding a modest two-game win streak, having mastered the Pirates 7-4 on Saturday. The Pirates’ Sunday starter, right-hander Red Lucas, had come over to Pittsburgh in a four-player deal the prior November after eight seasons and 109 wins with Cincinnati. O’Farrell sent Joe Shaute, a southpaw, out against the Bucs.

Shaute, conveniently nicknamed “Lefty,” had quite a row to hoe. The first four hitters in the Pittsburgh lineup would all end up in the Hall of Fame—center fielder Lloyd “Little Poison” Waner; his brother, right fielder Paul “Big Poison” Waner; shortstop Arky Vaughan; and left fielder Freddie Lindstrom. Another future Hall of Famer, third baseman Pie Traynor, wasn’t starting that day,10 Yet another, pitcher Waite “Schoolboy” Hoyt, in his 17th major league season but still only 34, was a Pittsburgh swingman.

Cincinnati brought four Cooperstown-bound players of its own to Forbes Field. First baseman Jim Bottomley and center fielder Chick Hafey both started; catcher Ernie Lombardi and pitcher Dazzy Vance would also see action in the game.

Although Traynor wasn’t taking any chances with the elements, “nice spring weather” with “bright sunshine” and “moderate temperatures”11 greeted an officially-noted 20,000 fans anxious to experience Sunday baseball. Baseball commissioner Kenesaw Landis was there as a guest of Pirate president William E. Benswanger, as was former Pennsylvania governor John K. Tener, who had also served as president of the National League. The Sporting News was complimentary, noting that Landis and Tener “thoroughly enjoyed” the game and “[i]t is apparent that Pittsburghers like the Sunday diversion and that they will patronize it liberally.”12

Lucas was a bit shaky in his Pittsburgh debut. After Gordon Slade singled to open the game, Lucas walked Adam Comorosky, a former Pirate involved in the November 1933 trade. But the righty settled down and left the two runners stranded, retiring Bottomley, Hafey and Mark Koenig.

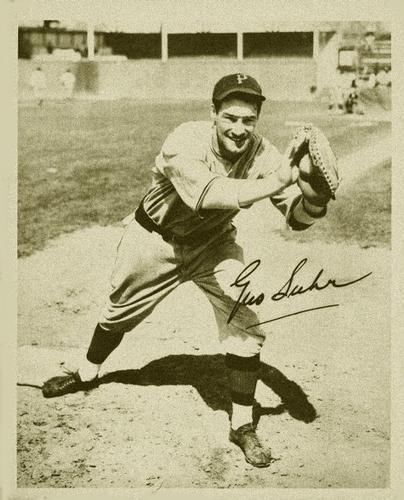

Shaute got both Waners in the bottom of the first inning before consecutive singles by Lindstrom, Vaughan, and Gus Suhr notched a run. Cincinnati tied the game in the top of the second on Ivey Shiver’s home run.

The Reds stranded two more runners in the third, then Pittsburgh broke the tie in its half of the inning. After Paul Waner grounded out, Lindstrom reached base on catcher’s interference by O’Farrell and Vaughan singled. Suhr, a durable and steady-hitting first baseman from California who had come up with the Pirates in 1930, then drove them both in with a triple to center. Rookie Cookie Lavagetto, playing in just his ninth major league game, tidied up the bases with a single, making it 4-1 Pittsburgh.

Shaute, whose “offerings seemed to strike no terror into the Pirates,”13 was gone in favor of Syl Johnson when Suhr batted again in the fifth inning, but Johnson fared no better. With two outs, Suhr lofted “an unusually long clout, the ball sailing into the distant part of the grandstand which extends back of right-center.”14 It was Suhr’s fourth RBI of the afternoon and it made the score 5-1.

With that apparently comfortable lead in the sixth, Lucas’s concentration slipped somewhat as he allowed a two-out single to O’Farrell and a home run to Johnson, one of four the pitcher hit in his 19-year major league career. The Pirates got those two runs back in their half of the seventh on a brother act by the Waners. Lloyd singled and advanced to second on an error by Hafey, and then Paul plated them both with a home run to make it 7-3. To keep things interesting, Cincinnati touched Lucas for two runs in their eighth on a walk sandwiched between a pair of singles — including a run-scoring single by O’Farrell—and an RBI groundout by Lombardi, pinch-hitting for Johnson. The Pittsburgh lead was down to 7-5.

Vance came on to pitch for Cincinnati in the eighth and the Pirates, to the delight of the Forbes Field faithful, kept the two-run carousel going against the former National League MVP.15 Lavagetto walked, and then Tommy Thevenow, Traynor’s early-season caddy at third, singled. A pair of infield outs moved Pirate runners to second and third, before Lloyd Waner delivered a single to restore the four-run margin.

Still chugging along in the ninth, Lucas finished what he started with a one-two-three shutdown inning to cap a 9-5 Pittsburgh win.

The win moved the Pirates to 5-4, but by June 17, following another Sunday home game16, this one a loss to the Giants that marked Pittsburgh’s seventh loss in eight games and left the club at 27-24, Gibson stepped down as manager. Traynor, wildly popular with the fans, replaced him “by mutual agreement.”17 The Pirates bounced their way to a 47-52 record the rest of the way, finishing fifth at 74-76 overall.

Acknowledgments

The inspiration for this account comes from fellow SABR member Doug Alden’s fascinating ESPN project “The Diary of Myles Thomas,” a day-by-day web-based account of the 1927 baseball season and urban life in 1927 observed through the genre of “real-time historical fiction” by Myles Thomas, a real-life member of the New York Yankees’ pitching staff. One of the numerous sidebar features complementing the Diary mentions the A’s’ 1926 injunction game and 1927 decision by the Pennsylvania Supreme Court upholding the blue laws. Having grown up as a Pirate fan enjoying Sunday games at Forbes Field in the ‘50s and ‘60s, my curiosity as to the first “legal” Sunday game in Pittsburgh was whetted. When the date of the Pittsburgh game proved elusive, an email to another fellow SABR member and Sunday baseball expert Charlie Bevis promptly produced it. My thanks to Doug, his associates at “The Diary,” and Charlie.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, I utilized the Baseball-Reference.com, Retrosheet.org, and Baseball Alamanc.com websites for box scores, play-by-play, player, team, and season pages, pitching and batting game logs, and other material pertinent to this account. The Newspapers.com website provided access to all of the cited newspaper articles except the item from The Sporting News, accessed through PaperofRecord.com.

Notes

1 The term “blue laws” is probably derived from “bluestocking,” in the sense of “puritanically plain or mean,” rather than the often-advanced theory that the term came from the blue paper on which all laws were written in the late 18th century. “Blue laws” entry, Online Etymology Dictionary, etymonline.com (accessed June 28, 2016).

2 “Pennsylvania ‘blue laws,’” Reading Eagle, April 16, 1977: 4.

3 The A’s defeated the White Sox 3-2. “Sunday Game Attracts Crowd,” Harrisburg Telegraph, August 23, 1926. See also: “The Fight for Sunday Baseball in Philadelphia,” Philadelphia Athletics, com, July 30, 2001 (accessed June 28, 2016).

4 “Supreme Court Decides Against Sunday Baseball,” Philadelphia Evening Bulletin, June 25, 1927, excerpted from The Diary of Myles Thomas.espn.com (accessed June 28, 2016).

5 “Anti-Blue Law Bill Signed By Governor Pinchot,” Pittsburgh Press, April 16, 1933: 1.

6 “Sunday Sports Backers Win Big Victory,” Pittsburgh Press, November 8, 1933: 1.

7 The first-ever post-referendum Sunday professional baseball game in Pennsylvania was a Philadelphia city series exhibition played between the A’s and Phillies on April 8, 1934. Charlie Bevis email, June 26, 2016. The Phillies won, 8-1. Reading Times, April 9, 1934: 17.

8 The A’s lost that game to Washington, 4-3. A week later, on April 29, 1934, as this game was being played in Pittsburgh, the Phillies lost at home to Brooklyn, 8-7.

9 “First Sunday Pirate Game,” Indiana (PA) Gazette, April 26, 1934: 2.

10 Traynor had played in six of the Pirates’ eight games in 1934 and was hitting .579 in 20 plate appearances. His early-season absences were due to a sore throwing arm, aggravated by “cold, damp spring weather.” Chester L. Smith, “The Village Smithy,” Pittsburgh Press, April 23, 1934: 27.

11 Edward F. Balinger, “Pirates Win First Sunday Game,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, April 30, 1934: 12.

12 The Sporting News, May 10, 1934: 3.

13 Balinger, “Pirates Win.”

14 Ibid.

15 Vance, age 43 during the 1934 season, had dominated the NL with Brooklyn and won the MVP in 1924. He was 28-6 with 30 complete games in 34 starts and 262 strikeouts in 308⅓ innings.

16 The Pirates were 7-5 in 12 Sunday home games in 1934.

17 Edward F. Balinger, “Pie Traynor Given Gibson’s Manager Post,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, June 20, 1934: 16-17.

Additional Stats

Pittsburgh Pirates 9

Cincinnati Reds 5

Forbes Field

Pittsburgh, PA

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.