August 1, 1932: The Beards versus the Braves: House of David visits Boston

“You shall not round off the hair on your temples or mar the edges of your beard” — Leviticus 19:27 1

The House of David touring baseball team let their beards and long hair grow, because of biblical stricture and just because it made them look more like the way many have imagined Jesus and the disciples to look.

The House of David touring baseball team let their beards and long hair grow, because of biblical stricture and just because it made them look more like the way many have imagined Jesus and the disciples to look.

What has been described as “a minor apocalyptic cult,” the House of David was a Christian commune founded in Michigan in 1903 which “sought to reunite the 12 tribes of Israel in preparation for the return of Jesus Christ at the onset of the new millennium. Members gave all their worldly possessions to the commune and were required to refrain from sex, alcohol, tobacco, and meat.” Its founder, Benjamin Franklin Purnell, a “self-proclaimed messenger of God,” also realized that a traveling baseball team would help spread the Word as he saw it.2 The team barnstormed around the country into the 1940s, and proved quite successful. They even carried portable lighting with them, enabling them to play night baseball in the years well before any major-league team played under lights.

The House of David team set up their lights at Braves Field on August 1, 1932, to play an exhibition game against the Boston Braves.

The first night baseball game ever played had in fact been more than 50 years earlier – in Hull, Massachusetts, on September 2, 1880, on the grounds of the Sea Foam House at Nantasket Beach. That newfangled invention of the day, the Weston light bulb, was but three years old at the time. (Edison’s first incandescent bulb was invented in 1879.) Three 100-foot-tall wooden towers were built, supporting 12 Weston lamps.3

By the 1930s, the House of David team would also retain advertised “ringers” such as future Hall of Famers Grover Cleveland “Pete” Alexander and Satchel Paige (years before the major leagues were desegregated). Alexander pitched for the visitors in this game at Braves Field.4 Game time was 8:30 P.M. on August 1. It was to be, noted the Boston Globe in advance, “the first game ever played in artificial light at a Boston big league park.”5

Some 2,500 came out to see Pete Alexander pitch for the House of David nine (he was the only beardless member of the team, and was quite unlikely to have abjured alcohol) against Braves right-hander Fred Frankhouse. It was about the same size crowd as had turned out for the day’s afternoon regulation National League game, which had seen the St. Louis Cardinals beat the Braves, 4-2.

The lighting came from several locations – two big trucks in foul territory near first and third bases to illuminate the infield, and 80-foot poles farther down both foul lines as well as in deep right and deep center. There were 36 lights in all, in clusters, which “made things almost as bright as some days.”

Umpiring were first baseman Art Shires of the Braves and a man named Lewis.

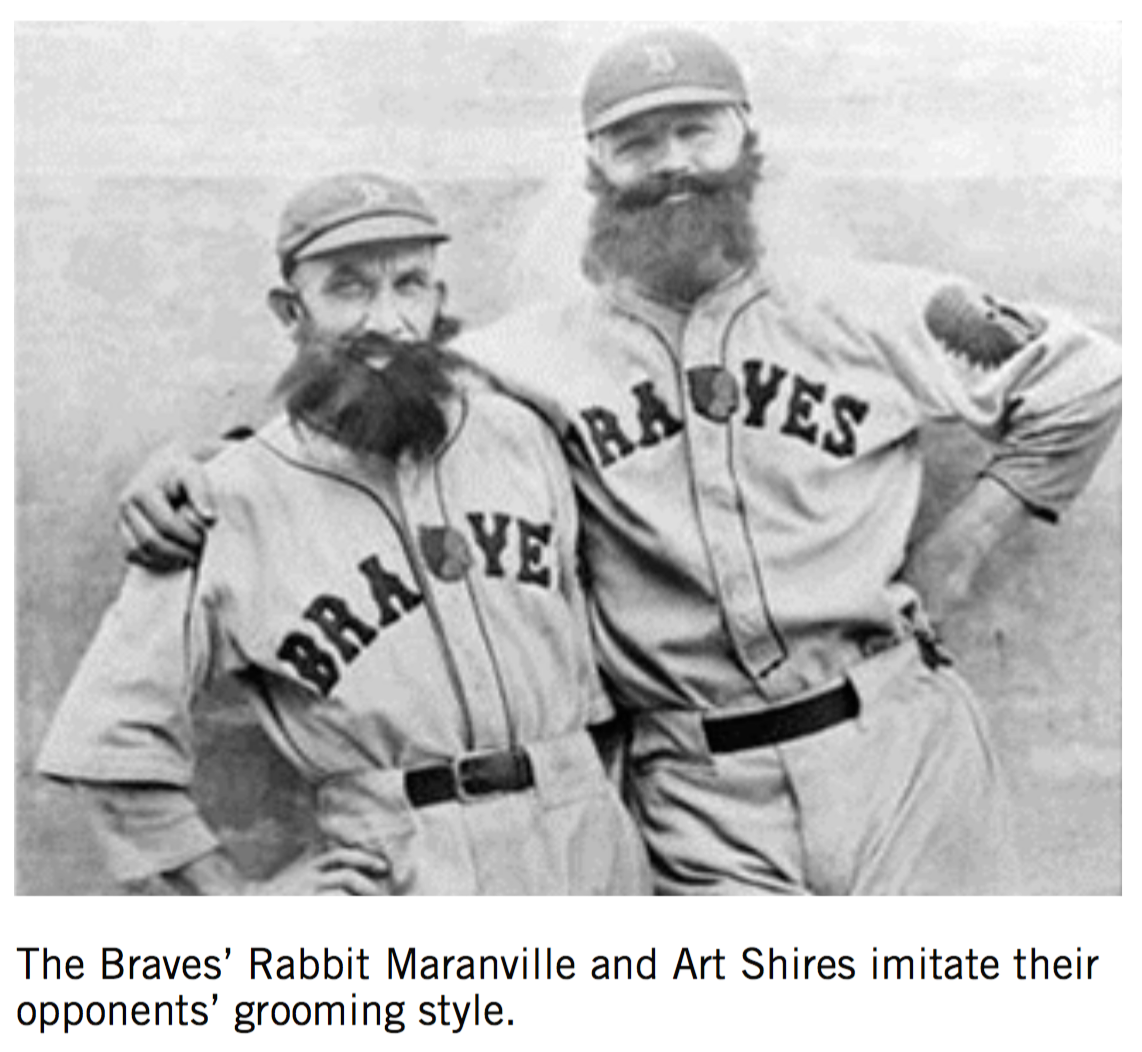

The game was one that ended with drama, though, all in all, the Boston Herald allowed that the game was “listless and eventless, except for the bits of comedy.” The House of David team specialized in pregame Harlem Globetrotter-style stunts and acrobatics with ball, bat, and glove. The Braves’ Rabbit Maranville wasn’t without some vaudevillian flair of his own.6 Predictably, the comedy centered on the Rabbit as well. Before the game, he’d put on an exhibition of infielding with an imaginary ball, performing all manner of tricks. And in the third inning, Braves Wally Berger and Wes Schulmerich both came out of the dugout sporting “big, luxurious beards” while Maranville “had a towel hanging down from the side of his cap, like an Arab of the desert.”

The Braves put the first run on the board, in the bottom of the first. Maranville led off and doubled to right field. With one out, he scampered to third base when Billy Urbanski hit into a fielder’s choice, and then scored on Berger’s fly to center.

The House of David team tied it up with one in the top of the third, when Alexander doubled and center fielder Henry LaFleur walked. An attempted sacrifice by second baseman Ralph Williams backfired and the 45-year-old Alexander was erased at third, but Frankhouse then walked the bases loaded. He struck out the next two batters, but not before LaFleur scored on a wild pitch.

A reliever named Grant (and dubbed “General” Grant or “Ulysses S.” by the Boston papers for his resemblance to the former US president) took over from “Old Pete” Alexander in the bottom of the third and held the Braves hitless until the seventh, though he’d doled out three bases on balls in the fifth, spared a run thanks to a caught stealing and a subsequent double play. Bruce Cunningham took over pitching from Frankhouse after six full. The Braves starter had given up four hits; Cunningham allowed only one hit in the final three frames.

The Braves collected only six hits; getting base hits had apparently not been easy for them in regular-season games at the time. They were robbed of one hit by House of David shortstop Gus “Buster” Blakeney, who “earned a big, generous hand” with his fielding of a ball hit by the Braves’ Earl Clark.

Blakeney later committed two errors, however, which set up the winning run. In the bottom of the ninth (and let’s recall this would not be a game called due to darkness), Schulmerich drove the ball to deep short; Blakeney’s throw was wide of the first-base bag as “Schul” slid in safely. Randy Moore tried to sacrifice, but pitcher Grant pounced quickly and threw to second – whereupon Blakeney dropped the ball. Then it was Fritz Knothe’s turn to put down a bunt. Grant grabbed that one, too, and again tried to cut down the lead runner. There was no error; his throw to third just didn’t arrive in time.

The bases were loaded with nobody out, and “the obscure Johnny Benson of Whitman” came to the plate. He was a “practice catcher” who, as it happens, never did play in the major leagues (and put in only two seasons of minor-league ball, with the Ogdensburg (New York) Colts of the Canadian-American League, in 1936-37). Benson had a big night on August 1, however. Grant delivered a pitch and Benson singled to short center field, driving in the go-ahead run: a walk-off 2-1 win for the Boston Braves.7

The game had lasted less than two hours.

The columnist “Sportsman” of the Boston Globe concluded, “As a novelty, night baseball is all right. As a permanent diet its value is at least doubtful.”8 The Boston Post saw less prospect: “The bright lights may attract in some cases, but not for those used to big league baseball. … (T)he nocturnal sport in this neck of the woods will hardly become popular.”9

This article appeared in “Braves Field: Memorable Moments at Boston’s Lost Diamond” (SABR, 2015), edited by Bill Nowlin and Bob Brady. To read more articles from this book, click here.

Sources

The Boston daily newspapers were the source of game play information. All of the direct quotations come from the Boston Herald of August 2, 1932, except as noted. Thanks also to Bob LeMoine for assistance in preparing materials for this article.

Notes

1 Leviticus, 19:27, The Bible. An illustrated history of the team is presented in Joel Hawkins and Terry Bertolino, The House of David Baseball Team (Columbia, South Carolina: Arcadia, 2000).

2 Boston Globe, October 27, 2013. In 1927 “Purnell stood trial for sexual assault against young girls in the commune, and for embezzlement. Five weeks after being convicted of fraud, the charismatic preacher died.” The religious colony failed, but the baseball team lived on.

3 For a more complete story of this 1880 game, see Bill Nowlin, Red Sox Threads (Burlington, Massachusetts: Rounder Books, 2008), 364.

4 Alexander should have been a major draw. He was a 20-year major-league veteran with a record of 373-208, his wins total tying him with Christy Mathewson for the most in National League history.

5 Boston Globe, August 1, 1932.

6 Indeed, Maranville actually took to the stage on the Keith Circuit at one time. See Walter “Rabbit” Maranville, “Rabbit’s Stage Career,” in Run, Rabbit, Run (Phoenix: Society for American Baseball Research, 2012), 34.

7 Bob Brady of the Boston Braves Historical Association writes, “Johnny Benson was a member of the BBHA and attended a couple of our reunions. He indicated that he spent the entire 1932 season in the bullpen, never getting into a game. A shoulder injury in the minors ended his pro career, although he played semipro ball in the area. One of his semipro teams’ batboys was Rocky Marciano. Benson met Ted Williams while making deliveries to Ted’s baseball camp in Lakeville.” E-mail from Bob Brady, October 22, 2014. Benson himself said, “I’m always embarrassed when I’m introduced as Johnny Benson, a catcher for the Braves, because I never even got into a major league game. All I did was warm up the pitchers.” When he was introduced to Ted Williams as a former Brave, he said, “I was only a bullpen catcher.” “Don’t put yourself down,” Williams said, with that blustery good will he was known for, then turning to the other people in the room he added, “this man was in the big leagues at a time when there were only 16 major league teams. You had to be good to just get there.” The Patriot Ledger (Quincy, Massachusetts), April 29-30, 2000.

8 Boston Globe, August 2, 1932.

9 Boston Post, August 2, 1932.

Additional Stats

Boston Braves 2

House of David 1

Braves Field

Boston, MA

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.