August 19, 1951: Eddie Gaedel pinch-hits for St. Louis Browns as smallest batter in baseball

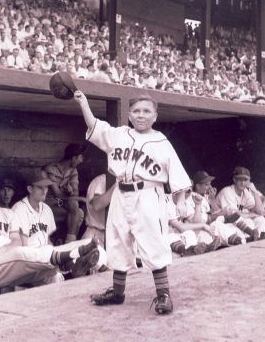

Bob Swift of the Detroit Tigers catches a pitch as St. Louis Browns pinch-hitter Eddie Gaedel stands at the plate on August 19, 1951. (SABR-Rucker Archive)

Search online for a definition of the word incongruous and among several provided on the Merriam-Webster website is “inconsistent within itself.” Well, that’s perfectly clear. In other words, something that just seems out of place.

Now, consider this: In one of baseball’s most iconic photographs, a batter, a catcher, and the home-plate umpire, each frozen in time in their customary positions, fill the frame: the umpire, at the left of the photo, standing with knees bent behind the catcher, peers over the kneeling catcher’s head; in the catcher’s upraised mitt, held slightly higher than the batter’s head, the ball is clearly visible, indicating that a pitch has just been delivered; and, crouching in the right-hand batter’s box, the batter, apparently having let the pitch go by, remains stationary in his stance, in anticipation of the pitcher’s next offering. It’s the classic triumvirate of contestants in America’s national pastime.

There is, however, one thing dramatically out of place in the photo. It is the “inconsistency,” the incongruity. The batter is very small; so small, in fact, the catcher, despite kneeling, nevertheless appears to tower over him. Though clearly short of stature, the batter is made even smaller as he leans slightly back over his flexed right leg. Although the faces and expressions of the fans in the background are blurred and difficult to make out, they undoubtedly share with the viewer the same shocked realization: The batter is, in the parlance of the day, a midget.

The idea for such an audacious stunt had been percolating in the mind of one man practically his whole life. St. Louis Browns owner, Bill Veeck Jr., for whose team the lilliputian had gone to the plate, was 4 years old when his father became president of the Chicago Cubs. As a teenager, the younger Veeck learned about team management during various stints as a vendor, ticket salesman and junior groundskeeper. He also got to know many of baseball’s most famous personalities, including New York Giants manager John McGraw, whom Veeck later credited with inspiring what would come to be his masterpiece as a baseball showman.

“McGraw,” Veeck recalled, “had been a great friend of my father’s. … Once or twice a season McGraw would come to the house, and one of my greatest thrills would be to sit quietly at the table after dinner and listen to them tell their lies.

“McGraw had a little hunchback he kept around the club as sort of a good-luck charm,” Veeck said. “He wasn’t a midget but was sort of a gnome. By the time McGraw got to the stub of his last cigar, he would swear to my father that one day before he retired he was going to send his gnome up to bat.”1 While McGraw never did, Veeck eventually sent his own diminutive batter to the plate.

It happened August 19, 1951. By then, Veeck had already firmly established a reputation for grandiose promotion that would, 40 years later, earn him enshrinement in the baseball Hall of Fame. In 1946, after five years as owner of the Double-A Milwaukee Brewers, during which time Veeck scheduled morning games for night-shift workers and staged weddings at home plate, he purchased a minority stake in the Cleveland Indians, which he held for three years, until a divorce in 1949 forced him to sell his share of the team. There, in addition to a World Series championship in 1948, Veeck expanded on his creativity by hiring a clown as coach, and also burying the Indians’ pennant when they couldn’t repeat as champions.

Veeck arrived in St. Louis in 1951 when he purchased the Browns. who shared Sportsman’s Park with the Cardinals. The Browns were an abysmal team. Despite recording their 36th win of the season during an impressive 20-9 thumping of the visiting Detroit Tigers the previous afternoon, the Browns had nonetheless lost an astounding 77 games, and Veeck was desperate to boost attendance. ”What can I do,” he pondered, “that is so spectacular that no one will be able to say he had seen it before? The answer was completely obvious: I would send a midget up to bat.”2 And so, he did.

Twenty-six-year-old Eddie Gaedel stood 3-feet-7-inches tall and weighed 65 pounds. Veeck had found him through a talent booking agent and had signed him, importantly, to a standard, valid major-league contract worth $15,400, which would amount to $100 for a single game. On this day, the Browns and Tigers were scheduled to play a doubleheader, the final two games of their four-game series. To maximize attendance, Veeck had decided to celebrate two birthdays – the 50th anniversaries of both the American League and the Browns’ sponsor, Falstaff Brewing Company. Veeck’s plan was to unveil Gaedel between the first and second games of the doubleheader. After the first game, won by the Tigers, 5-2, the intermission’s entertainment took the field, a motley crew of performers accompanied by an eight-piece band that featured, on drums, 45-year-old Browns’ pitcher Satchel Paige. Finally, after a parade of old cars and motorcycles circled the field and clown Max Patkin danced crazily on the mound, a seven-foot-tall birthday cake was wheeled to home plate. When Gaedel popped out, little could the fans have guessed the role he was about to play.

After Browns starting pitcher Duane Pillette got out of the first inning by stranding two Tigers runners, Detroit’s starter, right-hander Bob Cain, took the mound. Scheduled to lead off for the Browns was Frank Saucier. He never made it to the plate, however. As the public-address announcer notified the crowd of a Browns pinch-hitter, Gaedel emerged from the dugout wearing a uniform with the number ⅛ on the back and swinging three tiny bats, and strode toward home plate.

“Hey, what’s going on here,” bellowed home plate umpire Ed Hurley, advancing toward Browns’ manager Zach Taylor in the St. Louis dugout.3 Immediately Taylor, who had fully anticipated Hurley’s protest and was fully prepared to defend the move, was on the field. Taylor showed Hurley Gaedel’s contract; a telegram announcing Gaedel’s signing, which had been sent to American League headquarters and was noted with a requisite time stamp; and a copy of the Browns’ active roster, proof that St. Louis had room to add another player. In light of this evidence, Hurley allowed Gaedel to enter the game.

In his autobiography, Veeck later described what happened next. “The place went wild wildsic]. Bob Cain, the Detroit pitcher, and Bob Swift, the catcher, had been standing peaceably for about 15 minutes. … I will never forget the look of utter disbelief that came over Cain’s face when he finally realized that this was for real.”4 Cain could not know that Veeck had given Gaedel instructions not to swing. Regardless, Cain missed the strike zone with his first two pitches, then, continued Veeck, Swift “did just what I hoped he would do. He went to the mound to discuss the intricacies of pitching to a midget with Cain. And when he came back, he did something I had never dreamed of. To complete the sheer incongruity of the scene and make the picture of the event more memorable he got down on his knees to offer his pitcher a target.”5 With Swift on his knees, Cain threw two more fastballs, each missed, and Gaedel trotted to first base with a walk. As Gaedel stepped on first, Jim Delsing came in to run for him, and Gaedel’s major-league career was ended.

For those interested readers, the Tigers won the game, 6-2, behind Cain’s artful pitching. In the bottom of the first, Delsing advanced to third after replacing Gaedel, but Cain stranded two runners to end the inning. With the score tied 2-2, in the top of the seventh inning, the Tigers plated three runs on four hits to break the game open, 5-2. The following inning they scored their sixth run and an inning later handed the Browns their 79th loss of the season. Undoubtedly, though, on their way out of the park, the 18,369 fans in attendance, the largest American League crowd at Sportsman’s Park of the season, could talk about only one thing: the day a midget came to bat.

Sources

espn.com/classic/veeckbill000816.html

Gillespie, Ray. “Short Career for Midget in Brownie Uniform,” The Sporting News, August 29, 1951: 6.

Notes

1 Jerome Holtzman, “Veeck’s Midget Plan Was Picture Perfect,” Chicago Tribune, July 23, 1991.

2 baseballhall.org/hof/veeck-bill.

3 Holtzman.

4 Holtzman.

5 Holtzman.

Additional Stats

Detroit Tigers 6

St. Louis Browns 2

Game 2, DH

Sportsman’s Park

St. Louis, MO

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.