August 21, 1901: Joe McGinnity gives two spits over umpire’s calls

“Game forfeited to the Detroits,” umpire Tommy Connolly shouted as a band of policemen whisked him off the field, away from the angry mob and into his dressing quarters.1

“Game forfeited to the Detroits,” umpire Tommy Connolly shouted as a band of policemen whisked him off the field, away from the angry mob and into his dressing quarters.1

The room had become a familiar place for Connolly in Baltimore, and the yawps of impassioned players and fans a familiar tune.

Connolly, they surmised, missed an easy call in the fourth inning on this Wednesday afternoon when Orioles third baseman Jack Dunn zipped down the first-base line on an infield grounder. Dunn’s foot touched the first-base bag just before the throw arrived, Orioles players and their fans thought. Dunn was safe, they believed, but Connolly called him out.2

“It was the spark that started the blaze,” the Baltimore Sun reported the next day.3

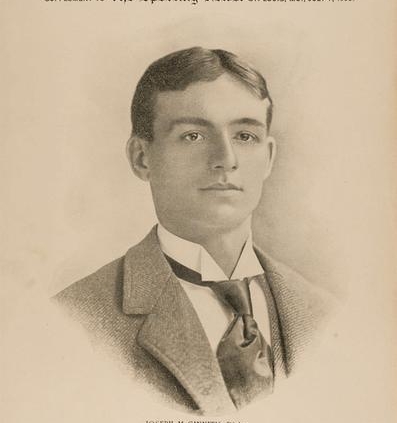

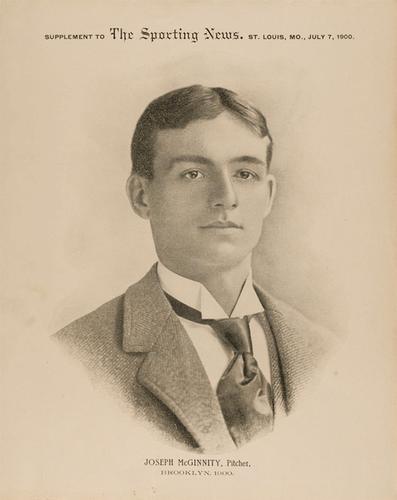

The Baltimore players voiced their frustration to Connolly. Most demonstrative, it turned out, was Orioles star pitcher Joe McGinnity. As players argued with the arbiter, fans poured out of the American League Park grandstand and bleachers wanting – again – a piece of Connolly. His umpiring had been suspect the entire game, and during Monday’s and Tuesday’s contests, and a few other games in the last couple of weeks.

In the heat of the fuss, McGinnity stomped at Connolly’s feet and spewed two shots of tobacco juice directly into Connolly’s face, the umpire claimed.4

Spectators in the new ballpark on the corner of Baltimore’s 29th Street and York Road had grown tired of Connolly’s inconsistencies. They had seen enough, and wanted another word with the ump. The scene soon turned chaotic. Baltimore Police Captain Charles W. Gittings5 and about 40 other officers quickly moved to surround and protect Connolly. They knew the routine. This was the fifth time Connolly needed protection from the Baltimore crowd in six games over a two-week span.6

Most of the attacks on Connolly were verbal, but 25-year-old Frank J.T. Allen, a clerk and loyal Orioles supporter, struck the umpire. Sergeant Max Mauer arrested Allen, who later in the day was fined $20 plus court costs.7

A couple of players – one from each side – also found themselves in police hands. One eager patrolman arrested Orioles shortstop Bill Keister for breach of peace although Keister was merely looking on, the Sun reported.8

Detroit’s Kid Elberfeld, for some unexplained reason, ran toward Connolly as the mess was beginning, but not meaning to get involved. Rushing by him was an Orioles player who nudged the diminutive Tiger into one of the rookie police officers. “The new ‘sleuth’ seemed bent on doing something heroic, and when he rushed up, Elberfeld was the first who came within reach,” the Sun reported. “Grabbing the inoffensive little shortstop by the collar, he trotted him off across the field at double-quick. The prisoner protesting volubly.”

Later that day, Justice White at the Northern Police Station fined Keister $1 and court costs for his charge of disturbing the peace. The judge dismissed Elberfeld’s case.9

Despite minor disturbances – if you can call getting tobacco juice in your face minor – Connolly escaped unharmed as police rushed him to his dressing area. As he left the field, he yelled the forfeit announcement, giving Detroit, which was already winning the contest 7-4, the victory.

Connolly stayed in the dressing room, with a policeman guarding its door, recovering from the ruckus and likely wiping tobacco juice from his mug. Police guarded Connolly for more than an hour, waiting for the offended to disperse.

They didn’t budge.

So Gittings and his crew cleared the ballpark. As the crowd walked away, police officers ushered Connolly to a carriage, which had been ordered by Orioles President Sidney Frank. The carriage, flanked by mounted policemen, hurried away carrying Connolly, Frank, and club director Miles Brinckley. Connolly’s carriage could not, however, escape the hisses and hollers from fans still in the streets.

The Baltimore Sun reporter covering the game suggested that Connolly’s delusions extended beyond the baseball field and that he, perhaps, had a greater impression of himself than was deserved. He wrote: “Some wag suggested that in his coach with outriders Connolly would more than ever imagine himself a czar and the crowd outside a band of nihilists.”10

Orioles players, fans, and even the press felt they had legitimate gripes with Connolly. The umpiring throughout the season, the Sun surmised, had been “remarkably good.”

“But in these last two series, Connolly’s work has been so flagrant as to incense the spectators beyond control,” the newspaper wrote. “Whether right or wrong, players and spectators believe that Connolly has intentionally given Baltimore the ‘worst of it,’ and every close decision against Baltimore lately, whether right or wrong, has added fuel to the flame.”11

Earlier in the August 21 contest, with Baltimore leading 3-2, Detroit loaded the bases. Doc Casey smacked a long fly ball off Orioles pitcher Harry Howell. Everyone in the park, it seemed, saw the ball fly foul. Tigers baserunners stopped running, thinking they needed to retreat to their bases and await the next pitch to the switch-hitting Casey.12

Connolly, however, saw the ball’s flight differently and barked, “Fair ball.”13 His judgment gave Casey a grand slam and it boosted Detroit to a 6-3 advantage. The call made the crowd furious and added another spark that soon ignited the blaze.14

Some criticism of the umpire came, too, from the Detroit players. The Baltimore Sun’s game stories of the previous two days were littered with details of ways Connolly blew calls.15

A day before Wednesday’s game, Orioles Secretary Harry Goldman suggested to Connolly that he ask American League President Ban Johnson to move him out of Baltimore for his safety. Connolly refused. That same day, Baltimore player-manager John McGraw, who suffered a season-ending knee injury that same day,16 wired a letter to Johnson. If Connolly stays, the letter read, he could cause tremendous tumult.17

Johnson stuck up for his umps, and that included suspending McGinnity indefinitely for his actions against Connolly.18 “His alleged offense,” the Baltimore Sun reported, “expectorating in Umpire Connolly’s face.” The Sun fearfully speculated that the suspension, which was thought then to possibly be for the remainder of the season, would drive McGinnity, who the paper said was “never a ‘rowdy,’” out of Baltimore and back to Brooklyn’s National League team, where he had played the year before. It would kill what small chances the “Orioles had to win the pennant.”19

Johnson, meanwhile, had plenty to say to the press regarding players’ and fans’ treatment of umpires, claiming arbiters could benefit from words of encouragement and less criticism.

“The vaporings of a partisan press, and the wild utterances of a disgruntled manager or player should not be taken seriously,” Johnson told the Chicago Record-Herald. “The best means to secure good umpiring is to keep the players away from the official. … The way to secure the best results from an umpire is to encourage him in his work rather that abuse him.”20

Heeding the suspension, the Orioles played on without McGinnity. And on a trip west to Chicago, the star pitcher and McGraw, newly fitted into his leg cast, paid a humble visit to Johnson at his office. “McGinnity confessed that he violated the rules and had also been guilty of conduct hurtful to the game, but he pleaded that his offense was not so serious as to warrant his expulsions,” the Baltimore Sun reported.21

After now having heard both sides of the argument, Johnson said, “I expect McGinnity to be pitching next week,” the article said.

Days later, Johnson stuck to his word and reinstated McGinnity on the condition that the pitcher pay a fine to the American League office and give an apology to Connolly. McGinnity agreed and pitched the same day, tossing a shutout against Milwaukee.22

“That is all there is to it,” Johnson said of his decision. “Circumstances, I find, were not all against the pitcher, and as he shows a disposition to rectify his wrong, I am glad to put him back in the game.”23

The Detroit Free Press disagreed, and advocated for a longer suspension for McGinnity. “A man who will spit in another man’s face is not fit for any society,” the paper wrote. “If a ballplayer can’t be a gentleman he should not be allowed to play, but should be sent back to carry the hod.”24

A newspaper reporter caught up with Connolly days after McGinnity’s suspension was overturned. He was umpiring the Orioles’ latest series in Cleveland, but had yet to hear from the pitcher. “And I don’t care to see him,” Connolly said. He would be willing to overlook a player, in the heat of the moment, punching him in the face or hitting him with a “rib roaster,” he said.

“My hand would go out to him in forgiveness in a moment,” Connolly said. “But when, as in McGinnity’s case, a man leaves the bench, rushes up to me and deliberately spikes me and spits in my face, as he did, twice in succession, I do not care for his apology.”25

Sources

The author used Baseball-Reference.com in addition to sources cited in Notes.

Notes

1 “Ends in Small Riot,” Baltimore Sun, August 22, 1901: 6.

2 “Ends in Small Riot.”

3 “Ends in Small Riot.”

4 “Connolly Still Angry,” Topeka State Journal, September 6, 1901: 2.

5 The Baltimore Sun Almanac, 1910, 14. The Sun article from August 21, 1910 mentions Gittings only by his rank and surname. The Almanac lists him as Charles W. Gittings, a captain in the Northeastern district.

6 “Ends in Small Riot.”

7 “Ends in Small Riot.”

8 “Ends in Small Riot.”

9 “Ends in Small Riot.”

10 “Ends in Small Riot.”

11 “Ends in Small Riot.”

12 “Ends in Small Riot.”

13 “Ends in Small Riot.”

14 “Ends in Small Riot.”

15 “One from Detroit,” Baltimore Sun, August 20, 1901: 6; “They Could Not Hit,” Baltimore Sun, August 21, 1901: 6.

16 “McGraw Out for the Season,” Baltimore Sun, August 23, 1901: 6. Doctors told McGraw “he would have to have his knee incased in a plaster cast and lie in bed for three weeks,” the Sun reported, “and that he could not play again this year.”

17 “Ends in Small Riot.”

18 “McGraw Out for the Season.”

19 “M’Ginnity Is Driven Out,” Baltimore Sun, August 23, 1901: 6.

20 “Discipline in Baseball,” Detroit Free Press, August 26, 1901: 8.

21 “M’Graw and Johnson Meet,” Baltimore Sun, August 31, 1901: 6.

22 “M’Ginnity Is Reinstated,” Baltimore Sun, September 4, 1901: 6.

23 “M’Ginnity Is Reinstated.”

24 “Timely Sporting Gossip,” Detroit Free Press, September 8, 1901: 9.

25 “Connolly Still Angry.”

Additional Stats

Detroit Tigers 9

Baltimore Orioles 0

*Game forfeited to visitors

American League Park

Baltimore, MD

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.