August 29, 1915: Jim Scott tosses shutout in 68 minutes, shortest game in White Sox history

The White Sox had good reason to want to get this day’s game over with as quickly as possible. The weary team had played eight games over the last six days, with five, including the last four, going into extra innings, as well as back-to-back doubleheaders on August 21 and 22. The 89 innings they’d labored in six days were believed to be a record.1

The White Sox had good reason to want to get this day’s game over with as quickly as possible. The weary team had played eight games over the last six days, with five, including the last four, going into extra innings, as well as back-to-back doubleheaders on August 21 and 22. The 89 innings they’d labored in six days were believed to be a record.1

Then, too, there was the weather. A band of cold rain had settled across the upper portion of the country, shortening or washing out four major-league games on the 28th and threatening more contests on the 29th. But it was the last scheduled game at Comiskey Park this season for Connie Mack’s Athletics and both hosts and visitors were eager to get the game in before the skies opened up. It had been prearranged that, to permit both clubs to catch eastbound trains, the game would be called, regardless of the score, at 3:00 P.M.2

Twenty-one-year-old rookie right-hander Tom Sheehan, with three wins and three losses, was Mack’s pick to start for the Athletics. Choosing not to compete financially with the free-spending Federal League, Mack had conducted a fire sale of his best players. The defending league champion A’s had collapsed to a last-place club; except for aging second baseman Nap Lajoie, first baseman Stuffy McInnis, and first baseman-outfielder Amos Strunk, Mack’s current roster was stocked primarily with rookies, castoffs, and players of less than major-league caliber. A July call-up from Peoria of the Three-I League, Sheehan was one of 24 pitchers to take a start on the mound for the Athletics in 1915.

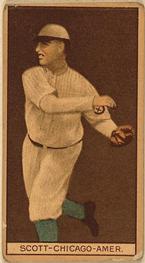

Some of the credit for Chicago’s rise was also owed to their 27-year-old ace, right-hander Jim Scott, who entered the game with a 20-7 record. If anyone on the White Sox might have been pleased at the prospect of playing in wet weather, it likely would have been Scott, known to sportswriters as “the curve ball wizard of the White Sox,”5 and “the best curve ball pitcher in baseball,”6 but to American League hitters as a purveyor of the mudball.7

Sources disagree on who introduced the mudball, although many credit Ed Reulbach8 as far back as 1905; others said Irvin “Kaiser” Wilhelm9 of the Federal League’s Baltimore Terrapins or Jack Ryan of the Pacific Coast League’s Los Angeles Angels10 popularized the pitch after the emery ball was banned following the 1914 season. Scott reportedly adopted the pitch during the White Sox’ spring training in Paso Robles, California,11 in 1915.

In throwing the mudball, Scott would moisten a portion of the surface of the ball — a squirt of tobacco juice in the glove worked quite nicely — then rub a little dirt on the spot. Pitching the ball so that the muddy side remained in the same relative position to the ground as it sailed to the plate, an able practitioner could make the ball break up, down, to either side, or in a combination of any two. Scott’s mudball, delivered with his trademark side-arm “clockspring” delivery,12 had confounded opposing batters all season, and helped Scott compile 20 victories, six by shutout, against seven losses through August 28. His top victims? The lowly Athletics, against whom Scott had won five decisions without loss, two of them by shutout.

Although the mudball was legal (except in the Federal League, where it was banned on August 9, 191513), the pitch had an ugly reputation. “[The mudball] is the most dangerous ball that has ever been introduced in the game,” said Doc White, a former major leaguer now pitching for the Vernon Tigers of the Pacific Coast League. “You can’t hit it, because it breaks four ways. I don’t know who discovered the mudball, but we found out about it through Jim Scott, the White Sox hurler, when the Sox were here on their spring training trip. … Somebody will get killed. It is far more dangerous than the emery ball because a pitcher can do far more with it. It breaks so fast that it will get some player sooner or later.”14

Although contemporary accounts fail to comment on whether Scott was relying heavily on the mudball against the Athletics on August 29, it’s a fair conclusion that, considering his success with the pitch all year and the conditions under which the game was played, the Athletics saw more than a few sudden drops and swerves at the plate that day. The hapless A’s flailed away at Scott’s deliveries, managing but three hits, singles by Lajoie and Rube Oldring and a double by Jack Lapp, spaced so far apart as to be “not even second cousins.”15 Scott struck out six and walked one. No Philadelphia baserunner but Lapp reached as far as second base.

The game was effectively over in the White Sox’ half of the third inning. Catcher Ray Schalk singled and Scott bunted him to second. Murphy singled to score Schalk, and first sacker Shano Collins followed with another single, putting runners on first and second. Eddie Collins walked, loading the bases, and a long single by Jackson drove Murphy and Shano Collins home. Left fielder Happy Felsch followed with the White Sox’ fifth base-hit in the span of seven batters, scoring Eddie Collins and Jackson.

With a five-run lead, the White Sox hustled to get the game in the books. “Every batter took a good healthy swing at nearly everything that could come over the pan and hit it if he could.”16 Sheehan scattered three more hits over the remainder of the game, all singles, and walked three more White Sox, but none figured in any scoring. No Chicago batter struck out, and aside from stolen bases by Murphy and Schalk, there were no accounts of daring play on the basepaths or overt attempts to get another rally going.

When the final out was recorded, the game was officially clocked at 68 minutes.17 The elapsed time set a major-league record for the shortest regulation nine-inning game,18 eclipsing a 70-minute contest between St. Louis and Brooklyn on September 29, 1904.19

The record would stand but 65 days. On October 4, 1915, the Brooklyn Superbas required only 63 minutes to dispatch the Philadelphia Phillies, 3-2, at Brooklyn.20

Today, the major-league record stands at 51 minutes, set by the Giants and Phillies on September 28, 1919. The Brown and Yankees surpassed the White Sox’ and Athletics’ record for brevity in the AL with a 55-minute game in 1926.

Sources

In addition to the sources listed in the notes, the author also consulted:

Atlanta Constitution.

Ithaca (New York) Journal.

Los Angeles Times.

The Sporting News.

Topeka Daily Capital.

Notes

1 “All Around the Texas League,” Houston Post, August 29, 1915: 17.

2 “Comiskey Park,” Chicago Tribune, August 29, 1915: 46.

3 Rick Huhn, Eddie Collins: A Baseball Biography (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2008), 116.

4 Kelly Boyer Sagert, Joe Jackson: A Biography (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Publishing Group, 2004), 58.

5 “Frank Isbell Sold Jim Scott to the Chicago White Sox,” St. Louis Star and Times, November 3, 1915: 11.

6 “How the Curve Became Baseball’s Greatest Discovery,” Ogden (Utah) Standard, September 25, 1915: 14.

7 “Scott First to Use Mud Ball,” Salt Lake Telegram, August 29, 1915, 5.

8 “ ‘Mud Ball’ Dances Right Up to Batter,” Philadelphia Evening Public Ledger, August 11, 1915: 11.

9 “’Mud Ball’ Is Banned by Federal League,” Bridgewater (New Jersey) Courier-News, August 14, 1915: 10.

10 “ ‘Tobacco Ball’ Newest from Coast,” Elmira (New York) Star-Gazette, August 25, 1916: 8.

11 “ ‘Mud Ball’ Dances.”

12 Jim Scott biography, sabr.org/bioproj/person/c679f80c [accessed March 6, 2018].

13 “Reulbach’s ‘Mud Ball’ Banned by Fed League,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 9, 1915: 12.

14 “The ‘Mud’ Ball Controversy,” Sporting Life, September 11, 1915: 11.

15 Ibid.

16 “Baseball,” The (Chicago) Day Book, August 30, 1915: 22.

17 Ibid.

18 Ibid.

19 “Superbas Will Soon Be in Last Place,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, September 30, 1904: 12.

20 “Phillies on Edge for Start of World Series,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, October 5, 1915: 24.

Additional Stats

Chicago White Sox 5

Philadelphia Athletics 0

Comiskey Park

Chicago, IL

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.