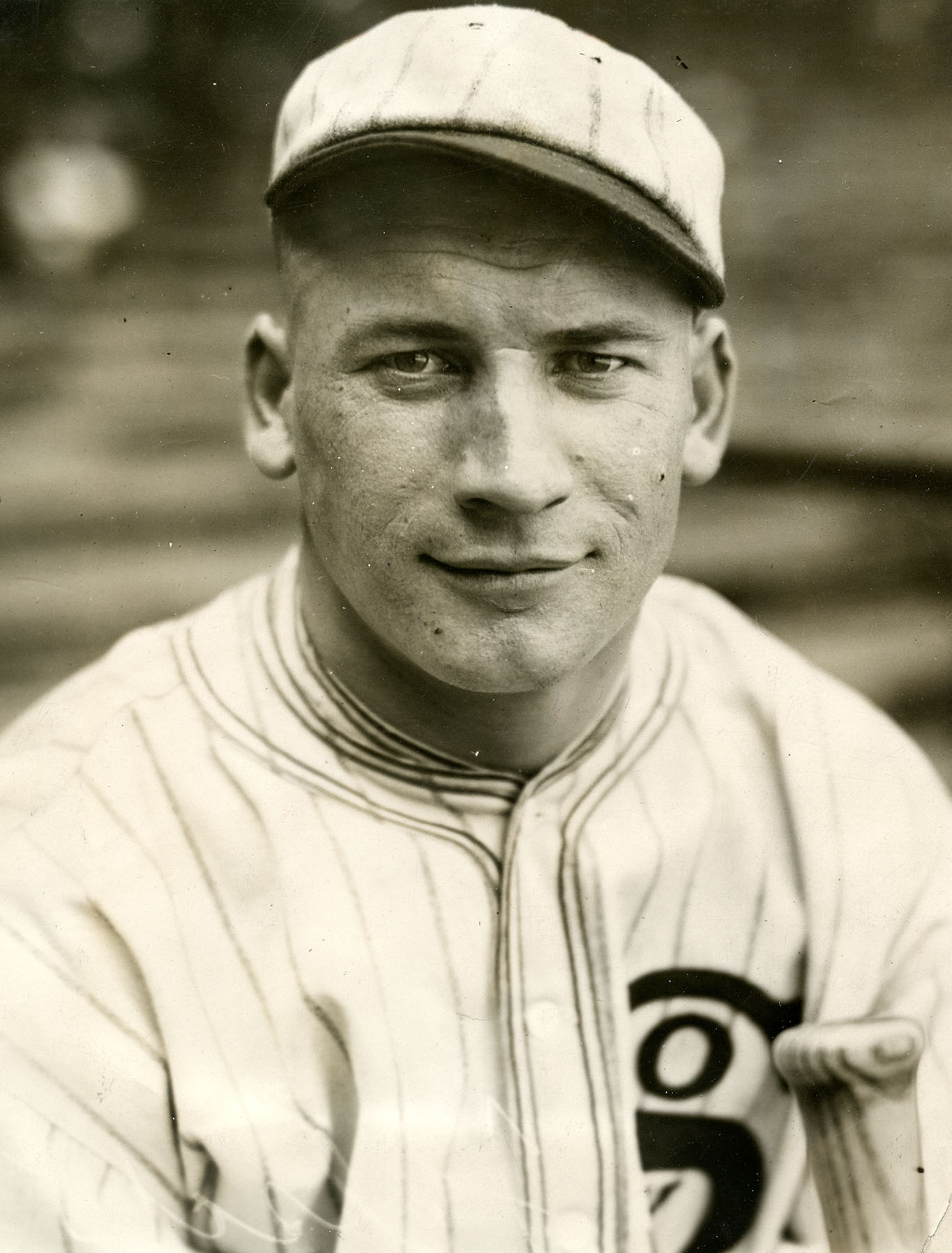

Happy Felsch

The Black Sox Scandal shocked the sporting public and led to fundamental changes in the governance of professional baseball. Central to this astonishing fix were eight Chicago White Sox ballplayers, including star center-fielder Oscar “Happy” Felsch.

The Black Sox Scandal shocked the sporting public and led to fundamental changes in the governance of professional baseball. Central to this astonishing fix were eight Chicago White Sox ballplayers, including star center-fielder Oscar “Happy” Felsch.

An unpretentious Milwaukee native, the “Pride of Teutonia Avenue” only left his hometown to play ball. Felsch, one of 12 children of German immigrants, rose to the pinnacle of the baseball world only to be consigned forever to the sport’s hell.

White Sox left fielder Shoeless Joe Jackson and third baseman George “Buck” Weaver have garnered the most attention of the “Eight Men Out,” becoming mythologized in books and movies. Happy Felsch was just a common Milwaukeean caught up in momentous events of the turbulent 1910s and ’20s. More than 40 years later, his account of those events would be the primary source for Eliot Asinof’s book Eight Men Out and the movie that molded present-day understanding of the fix.

- Learn more: Click here to view SABR’s Eight Myths Out project on common misconceptions about the Black Sox Scandal

Oscar Emil Felsch, who grew up to be arguably the best baseball player ever produced by Milwaukee’s north side, was born in 1891 in a German working-class neighborhood. His birth certificate does not exist because there are no Felsch family public-health records from that era.1 Many baseball historical resources list Felsch’s birth date as August 22, 1891, or unspecified dates in 1893 or 1894. However, his 1943 application for a Social Security number and his 1964 death certificate both state that he was born on April 7, 1891, to Berlin natives Charles and Marie Felsch (née Tietz or Tiegs).2 Charles was a north side carpenter.3

In the census of 1900, young Oscar was one of 10 living Felsch children and one of seven still residing in a mortgaged 26th Street frame house. He did not read or write in 1900 but eventually could after receiving a sixth-grade education. This lack of further formal education proved to haunt Felsch when he had to deal with shrewd baseball executives, underhanded gamblers, lawyers, and college-educated teammates.4 The teenage Oscar went to work as a $10-a-week factory laborer and shoe worker, giving all but 25 cents of his pay to his father.5

Felsch’s rise from the Milwaukee sandlots was due in no small part to his ballplaying dad and brothers. Reputed to be a first baseman of great ability, Charles had three more sons who played on area teams. As typical members of the aspiring working class, the boys hoped to develop their reputations in prominent local leagues in order to gain notice from pro scouts.6 Following the example of many other second-generation German children, the youthful Oscar turned away from individual sports like gymnastics and wrestling and gravitated toward the popular American team game of baseball. A member of the Turnverein (or Turners, a German gymnastics movement that emphasized physical education), the powerfully built wrestling champion eventually gave up grappling for baseball.

The broad-shouldered Felsch, listed at heights between 5-feet-9 and 5-feet-11 and weights of 160 to 190 pounds over his playing career, first appeared on the local baseball scene in 1911.7 Now employed as a shingler, the right-handed throwing and hitting shortstop-third baseman spent his spare time performing for Sisson and Sewell, a semipro club sponsored by a local clothing store. Their Sunday contests allowed Felsch to display his developing skills. The Milwaukee Sentinel noticed the budding star’s four hits and seven successful fielding chances on August 6, declaring, “Felch [sic] played a swell game at third.”8

In 1912 Oscar played with four semipro teams throughout Wisconsin. The star Sewell shortstop left in mid-June to sign with Manitowoc of the higher-level Lake Shore League, then later played with Grand Rapids (now Wisconsin Rapids). Felsch then manned third base behind pitcher Stoney McGlynn, a former St. Louis Cardinal and Milwaukee Brewer. Larger crowds in Lake Shore League towns like Racine and Sheboygan gave an athlete of Felsch’s caliber the opportunity for more lucrative paydays.9 By late August, the Grand Rapids team had disbanded and Felsch signed on with Stevens Point for the rest of the season.

Felsch’s easygoing nature and wonderful smile made the family nickname “Happy” a perfect fit. Newspapers adopted the sobriquet as early as 1912. At times he even preferred practices to games just for the sheer joy of hitting, fielding, and running.10 In 1913 Felsch continually appeared in the dailies as he advanced to minor-league ball with the Milwaukee Creams of the Class C Wisconsin-Illinois League. The youthful shortstop made a powerful first impression on Opening Day at Athletic Park (later called Borchert Field) as he went 5-for-5 with a grand slam in the first inning, drove in seven runs, and made two errors. The Creams defeated Appleton, 12-5, in the April 30 game, played immediately after the American Association Brewers contest.11

Felsch continued his impressive hitting, including a three-homer game in Oshkosh, and sensational but error-prone fielding during his abbreviated stay in his hometown. Meager crowds for this farm team of the higher-level Brewers forced the Creams to move on June 28 to Fond du Lac, where they became the Molls. There Felsch continued to spend time at both shortstop and his new position, right field.12

By early August, the Brewers called up their phenom. This allowed him to vault to Double-A, the top category of the minors, bypassing the B and A levels. Following are Felsch’s impressive Deadball Era statistics with the Cream/Molls, his first professional team: 18 home runs and 16 stolen bases with a .319 batting average in 357 at-bats. The promising youngster’s future was in the outfield as he committed only two errors in 34 games there (.971 fielding percentage) while booting the ball 36 times in 58 games (.868 fielding average) at shortstop.13

Felsch did not play often for the pennant-winning Brewers in 1913, as he needed polishing. He finished with a batting average of .183 with two home runs in only 26 games.14

In 1914 the muscular Felsch showcased his major-league potential both at the plate and in the outfield. He set home-run distance records in Milwaukee (over 500 feet at Athletic Park, by one account) and Kansas City, and led the American Association in round-trippers with 19. Felsch batted a potent .304 with 41 doubles, 11 triples, and 19 stolen bases for the repeat-champion Brewers. He demonstrated his outfield prowess with great range and a rifle arm.15

By early August the Brewers, an independent club, knew they owned a star fit to sell to the highest major-league bidder. The Senators, Cubs, White Sox, Giants, and Reds were scouting the left fielder. On August 8 the White Sox acquired Felsch for $12,000 plus an infielder and an outfielder from their organization. The Brewers were delighted that Chicago allowed their “fence breaker” to remain in Milwaukee for the duration of 1914. Felsch, declared the greatest Brewer ever by their business manager, Lou Nahin, then signed a two-year contract with Chicago at a salary of $2,500 per year.16

The 1915 season developed into an eventful one for the White Sox’ rookie center fielder. Not only did Felsch make his major-league debut on April 14 in St. Louis with a single and a stolen base, but he also got married.17

The 1915 White Sox started their steady ascent toward the top of the American League by rising from sixth place to third with a 93-61 record. This was due to the addition of energetic 33-year-old manager Clarence “Pants” Rowland and five new position players, including future Hall of Fame second baseman Eddie Collins, Shoeless Joe Jackson, and Felsch. The newcomer in center finished with a .248 batting average, three home runs, and 16 stolen bases in 121 games as a semi-regular. Felsch’s numbers could have been stronger except for a nagging leg injury he suffered early in the season.18

After the conclusion of the hotly contested Chicago City Series between the White Sox and Cubs, the handsome, square-jawed 24-year-old major leaguer returned to Milwaukee, where he married Marie Wagner, described on the marriage certificate as a 22-year-old north side homemaker, on October 27.19

Felsch spent what should have been his honeymoon getting his first experience with the judicial system. On October 29 the newlywed was asked to testify in pitcher Cy Slapnicka’s lawsuit against the Brewers for back pay. After the case was postponed until December, Felsch, Slapnicka, and the Philadelphia Phillies’ Fred Luderus, also from Milwaukee, embarked for Little Chute, Wisconsin, for a Sunday exhibition contest.20

The coming 1916 baseball season surely brought hope to Felsch and the White Sox. The promising club advanced to second place, overcoming a slow start to finish only two games behind the Red Sox. Charles Comiskey, the White Sox owner, was spending money to make money. Adding a pitcher of the caliber of Claude “Lefty” Williams to a staff that already included stars Eddie Cicotte, Red Faber, and Reb Russell helped the White Sox break their attendance record with 679,923 fans, 140,462 more than in 1915.21

Comiskey Park loyalists enjoyed watching Felsch belt seven home runs, out of a team total of 17. He led the Deadball Era White Sox and tied for third in the American League. Suddenly the sophomore from the sandlots of Milwaukee was in the upper echelon of AL hitters as he batted an even .300 and finished sixth in the league with a slugging average of .427. Under the tutelage of coach William “Kid” Gleason, the sure-handed Hap, an honorable mention member on Baseball Magazine’s AL All-America Baseball Club, topped all AL outfielders with a fielding percentage of .981.22

For Happy Felsch it would never get better than 1917. In only his fifth season of professional baseball, he had become a national hero, thanks to a remarkable regular season and an exceptional World Series. The White Sox center fielder was in a class with future Hall of Fame outfielders Tris Speaker and Ty Cobb thanks to his 1917 statistics: .308 batting average (fifth in American League); 102 RBIs (tied for second with Ty Cobb, first White Sox player ever with 100 RBIs); 440 putouts (first among AL outfielders); and six home runs (tied for fourth in AL).

Comiskey had picked up shortstop Swede Risberg and first baseman Chick Gandil to round out the starting lineup. Although both players were welcome additions on the diamond, they helped form divisive cliques in the clubhouse. Gandil also retained his connections to gamblers. Felsch fraternized with the boisterous, card-playing Risberg/Gandil group that was often in conflict with the higher-educated Ray Schalk/Eddie Collins faction. The seeds of discord that led to the 1919 scandal were sown.23

Climaxing this year of destiny was the 1917 World Series. Game One, played at Comiskey Park on Saturday, October 6, was decided by a “loud and vicious clout from the trusty bludgeon of Felsch.” “Milwaukee’s famous beef and brawn” hit a long home run to deep left field, giving the White Sox a 2-0 lead in a game they eventually won 2-1 over the New York Giants. The center fielder also made a sensational one-handed cutoff play of a Giant double, preventing a round-tripper.

Felsch, who drove his new Packard from Milwaukee to Chicago the day before, was rewarded with two $50 Liberty Bonds, including one from entertainer Al Jolson. He also accepted a new suit, hat, shoes, and other clothing articles from Chicago merchants. Milwaukeeans, thrilled over Felsch’s success, presented him with a baseball-shaped diamond stickpin before Game One and jokingly threatened to take it away if he did not hit a home run. Felsch proceeded to earn the pin and much adulation by slugging the only Sox homer in that fall classic. A thousand Milwaukee fans, including Felsch’s father and a brother, were at Comiskey Park that day. Back home, 20,000 more flocked to local electric scoreboards in theaters or to tickers and blackboards in restaurants and businesses. Fans were just as loud as if they were at the game and remained in a frenzy for 15 minutes after the home run.24

In Game Two, Chicago continued its winning ways as the “pride of the Cream city” contributed to the 7-2 victory with a hit-and-run single and several outstanding fielding plays. In Milwaukee, Felsch fans went wild again as 35-cent tickets to the electric-scoreboard venues were scalped for $1. That Sunday evening the White Sox and Giants left for New York, arriving on Monday afternoon. Game Three, scheduled for Tuesday at the Polo Grounds, was rained out. Off-the-field news included a flattering invitation for Felsch, Eddie Cicotte, and outfielder John Collins to appear in New York vaudeville. The three did not say whether they accepted.25

The Giants recovered to tie the Series at two games each with back-to-back shutouts of the hard-hitting White Sox. Comiskey Park hosted Game Five on Saturday, October 13. Chicago came back from a 5-2 deficit to win 8-5 with Felsch going 3-for-5. The teams traveled again to New York where, on Monday in Game Six, the White Sox captured the Series with a 4-2 victory.26

The White Sox were the toast of the Windy City as they returned to thousands of exultant fans, orators, and two big brass bands. The ballplayer that “made Milwaukee famous” was welcomed back with numerous parties, receptions, banquets, and dances throughout his proud hometown. Friends, local clubs, and city officials helped to arrange the celebrations that honored the man New York sportswriters believed made the difference in the Series, with both his bat and his glove. The smiling ballplayer enjoyed the attention, but insisted that he not speak in front of throngs of his clamoring fans.

In addition to his World Series check of $3,669 (almost matching his salary of $3,750), the popular star received presents including a gold watch, a set of silverware, and $100 worth of shares in American Aircraft. The papers glorified Felsch by claiming that he made $10,000 a year and accepted enough complimentary drinks to start his own brewery. After all the honors and gifts were bestowed upon Felsch, “the greatest citizen the north side has ever produced,” he left for the solitude of a three-week fishing and hunting trip in the northern woods.27

Major-league baseball, the White Sox, and Felsch experienced tough times in the intensified war year of 1918. The season was shortened so that baseball could comply with the “work or fight” edict of May 18. This decreed that any male between 21 and 31 years old in a nonessential job must enlist, secure a war-related job, or be reclassified with a lower draft number. Players who did not enlist hurried to take exempt jobs in shipyards, steel mills, war-production factories, and farms. Many of them, now subject to criticism as slackers, then played ball in industrial leagues.28

The defending champion White Sox got off to a rocky start as the train taking them to spring training derailed March 18 in Texas. No one was hurt. Then Felsch missed the beginning of camp because of a sudden illness. The season continued downhill as the White Sox lost many key players to the war effort. The club finished in sixth place with a 57-67 record before only 195,081 Comiskey Park customers. This was a significant decline from the 684,521 who watched the 100-54 pennant winners of 1917.29

The glory of 1917 must have seemed like a distant memory to Happy Felsch as he struggled both on and off the field in 1918. The star outfielder left the White Sox for 12 days in May as he visited a seriously injured brother in a Texas Army camp. Alarming his family and manager Rowland, the distraught Felsch remained incommunicado during the entire trip.30 The “mighty Happy” departed for good on July 1, leaving Rowland with a punchless, spiritless shell of a team. Surprising the defending champs with his sudden resignation, Felsch announced that he was taking a war-effort job at the Milwaukee Gas Company for $125 a month plus earnings from weekend semipro ball. This paled in comparison to the $3,750 contract he walked away from. In an effort to boost attendance, the Kosciuskos of the Lake Shore League quickly signed the former World Series star.31

Normally a modest man, Felsch kept quiet about the dispute until July 18. That day, the Milwaukee Sentinel reported the disgruntled star’s desire to return to the American League with any team other than the White Sox.32 The Sporting News reported that Felsch had left because of disputes with Comiskey over pay, abstinence from drinking, and the Texas journey, plus a personal conflict with Eddie Collins.33

“Milwaukee’s most famous diamond gladiator” was welcomed home by his many local admirers. The Koskys now played before packed houses both on the road as well as at Milwaukee’s South Side Park and Athletic Park. As expected, Felsch hit very well and showed his versatility by handling all three outfield positions, first base, and catcher. Not only did he remain a Kosky through early October but he also participated in several “All-Star” games in Milwaukee and Chicago. These contests included major leaguers Braggo Roth, Dickey Kerr, Jack Quinn, Fred Luderus, and others.34

After the 1918 season, Comiskey replaced manager Rowland with popular longtime White Sox coach Kid Gleason, stating that Pants had lost control of the team. Even though the war ended on November 11, heading off the expected shutdown of the 1919 season, 1918 had a profound impact on the White Sox. The club was torn by dissension over wage disparities and disputes between players who enlisted in the military versus those who took exempt war-effort jobs.35 Owners and the press resented athletes who avoided military service by working for companies with baseball teams. A disgusted Comiskey, alluding to Felsch, Joe Jackson, and Lefty Williams, went so far as to say, “There is no room on my club for players who wish to evade the army draft by entering the employ of ship owners.”36

Comiskey conveniently set aside his anger in order to rebuild his remarkable team. With Gleason serving as a capable conciliator, the White Sox promptly brought back stateside war workers Felsch, Jackson, and Williams. Felsch quickly regained his form in 1919, leading the American League with 32 outfield assists and 14 double plays.37 Four of the assists came on August 14, tying a major-league record. Accepting 12 chances on June 23 let the gifted ball hawk tie another American League record. His 14 double plays are still tied for the single-season record as of 2014.38

Felsch batted a solid .275 for the top run-producing team in the majors and slugged seven home runs, tying Jackson for the club lead. His 24 homers that decade were more than any other White Sox player hit.

Many of these statistics could have been more impressive had the owners not shortened the 1919 campaign. Anticipating lower attendance as the public recovered from the war, the baseball moguls cut the regular season from 154 to 140 games. In addition, American League rosters were reduced from 25 to 21, and salaries were depressed in anticipation of lower gate receipts. These concerns proved to be unfounded as war-weary fans flocked back to the national pastime. Attendance rose to 627,186 from 195,081 for the AL champion White Sox and to 6.5 million from 3 million in the majors. In an effort to recoup some revenue lost to the ill-advised shortened season, the owners extended the World Series between the Cincinnati Reds and the Sox from seven to nine games.39

Felsch’s banishment from Organized Baseball was a result of the 1919 fall classic, his second and last. Some of the White Sox, playing in an atmosphere poisoned by unchecked wagering and lower-than-market salaries, were eager to cash in. Owners and league executives generally ignored betting as they encouraged any interest in their sport. Baseball was revered as upright and patriotic. Charles Comiskey stated in an authorized 1919 biography, “To me baseball is as honorable as any other business. … It has to be or it could not last a season out. Crookedness and baseball do not mix.” At the very same time, his own players were mixing the two.40

In this era long before free agency, many players received wages far below their market value. Bound to their teams by the reserve clause, they could sign for what the owners offered or go home. Black Sox Felsch, Jackson, and fix organizer Gandil were rightly upset that their three salaries combined were less than the $15,000 made by college-educated Eddie Collins. The eight Black Sox averaged $4,300 in 1919.41 Certainly, Felsch’s $3,750 annual 1917-19 contracts (plus the potential for $5,000 in World Series pay) compared favorably with the average blue-collar pay range of $1,000 to $2,400, cited by Steven Reiss in his 1999 book, Touching Base: Professional Baseball and American Culture in the Progressive Era.42

It is still unclear exactly how the Series was fixed and who the principals were. However, many of the favored White Sox did play poorly, whether it was because they took money from gamblers, feared retribution from gangsters, or endured an ordinary slump. Felsch himself was full of contradictions, both in his on-field performance as well as in interviews in later years.

At the plate Felsch produced only a .192 batting average with one extra-base hit, a double, in the eight-game Series loss.43 The hard hitter made satisfactory contact but was robbed several times by superb Cincinnati fielding. In hindsight, some sportswriters looked at his sudden inability to advance runners, as well as several questionable running and fielding misplays, as possible proof of Felsch’s involvement in a fix. After botching catches in Games Five and Six, the normally sure-handed center fielder was demoted to right field for Game Seven.44 The Milwaukee Sentinel believed that the hometown hero hit in bad luck and was just “outshone” by Cincinnati’s Edd Roush. The paper did not hint at a fix, but stated that the White Sox were down and lethargic. After Felsch hit his two-bagger, the Sentinel exclaimed, “Felsch was also on the job, much to everyone’s surprise, and walloped a double.”45

After dropping the World Series, the defeated Sox returned home with promised losers’ shares of $3,254 and without their normal triumphant attitude and the $5,207 winners’ portions, up to then the largest in baseball history. Comiskey, responding to what he called “nasty rumors,” even publicly offered a $20,000 reward to anyone with evidence of a fix, but added, “I believe my boys fought the battles of the recent World Series on the level, as they have always done.” Later he announced that he was withholding the losers’ shares from eight of his players “pending further investigations.” Despite his protestations of ignorance, Comiskey chose the correct eight.

The Sentinel sarcastically reported, “Felsch is back home and will amuse himself on the bowling alleys this winter. If he makes as many strikes as he did in the world’s series he ought to be good for a couple of 300-scores.”46

Rumors of a fix were flying even before the first game. Many sportswriters heard them, but they never appeared in print. The day after the Series ended, one of the most prominent writers, Hugh Fullerton, urged his readers to “forget the suspicious and evil-minded yarns that may be circulated.” However, he added, “There are seven men on the [White Sox] team who will not be there when the gong sounds next Spring. …” Later Fullerton wrote that he had been present when manager Gleason told Comiskey that the rumors were fact.47

The offseason proved disturbing for Happy Felsch. In November he and other Black Sox were the subjects of a private investigation. Comiskey hired detectives to check if his players were making suspiciously large purchases or lifestyle changes.48 Operative number 11 of Hunter’s Secret Service conducted the Felsch surveillance only to uncover contradictory information. After culling tips from many north side taverns, the investigator discovered that Felsch had recently moved from his father’s home on North 26th Street back to his in-laws’ neighborhood on Teutonia Avenue. While the slugger was on a duck-hunting trip, number 11 gained access to the Felsch apartment under the pretense of renting a furnished room. The eight-room, no-bath living quarters above a grocery were crowded as the Felsch family lived with Marie’s parents, sister, and the sister’s two small children. The private eye believed the neighborhood to be poor. He found Hap’s recent purchase of a new $1,800 Hupmobile — a solid automobile bought by those rising from the working class — inconsistent with living in a cramped $22-a-month apartment.49

After the secret investigation, Comiskey was left with no choice but to mail the $3,254 checks. He could find no evidence that anyone but Gandil went on a spending spree.50

Felsch then received an unexpectedly generous contract from the White Sox. Comiskey’s top assistant, Harry Grabiner, made a special trip to Teutonia Avenue in late 1919 to ink the center fielder to a 1920 contract that included a surprising $3,000 raise. Felsch, taken aback by Comiskey’s sudden largesse, signed even as Grabiner reminded him that he could not play with anyone but the White Sox. In addition, Grabiner mentioned the swirling scandal rumors and called for Felsch’s silence, both with the press and with American League inquisitors.51 It was apparent that Comiskey desired his stars back and was finally willing to invest in salaries commensurate with their talents in order to purchase their silence. Further investigations could result in ruinous player punishments.52

Felsch’s finest year on the diamond was to be his last. He established career highs of 14 home runs (first on the White Sox and fourth in the AL behind Babe Ruth’s unbelievable 54), 188 hits, 88 runs, 40 doubles, 15 triples, 115 RBIs, and a .338 batting average.53 Batters in 1920 enjoyed a livelier ball, the new requirement that umpires keep only fresh, unmarred spheres in play, and the outlawing of trick pitches (except for the grandfathered spitball pitchers).54 The 29-year-old, now in his prime, was considered one of the American League’s top players, pacing the circuit’s outfielders with 10 double plays.55

After the defending American League champs trained in Waco, Texas, they arrived at Milwaukee’s Athletic Park for several preseason exhibitions with the Brewers. Felsch, the hometown idol, responded to a rousing ovation from the 5,000 fans on April 10 with a 2-for-4 day.56 The White Sox proceeded to stay in the 1920 pennant race until the events of a turbulent September caused them to succumb to the Cleveland Indians.

September of 1920 proved to be the final month of Happy Felsch’s brilliant career. On the 7th a grand jury was impaneled in Chicago to investigate the possible fix of an August 31 Cubs-Phillies game. After the hearings began on September 22, the focus quickly shifted to the tainted 1919 World Series. On Monday, September 26, Felsch suited up for the last time in an 8-1 win over the Detroit Tigers. Two days later, Cicotte and Jackson, counseled by Comiskey’s attorney, confessed to the grand jury. Immediately after the indictments, Comiskey suspended the seven implicated players. The Sox were only a half-game behind the Indians.57

By now, the fix story was front-page national news. Reporter Harry Reutlinger of the Chicago Evening American was looking to secure his scandal facts first-hand from one of the players. He was advised to visit Felsch, who was uneducated but considered affable enough to talk. Armed with a bottle of scotch, Reutlinger quickly got Felsch, who was in a bathrobe soaking his swollen big toe, to open up.58 In a September 30, 1920, article, Felsch verified Cicotte’s confession:

“Well, the beans are all spilled and I think that I am through with baseball. I got my $5,000 and I suppose the others got theirs too. If you say anything about me, don’t make it appear that I’m trying to put up an alibi. I’m not. I’m as guilty as the rest of them. We were in it alike. I don’t know what I’m going to do now. … I’m going to hell, I guess. … I wish that I hadn’t gone into it. I guess we all do. … I never knew where my $5,000 came from. It was left in my locker at the clubhouse and there was always a good deal of mystery about the way it was dealt out. That was one of the reasons why we never knew who double crossed us on the split of the $100,000. It was to have been an even split. But we never got it. … But when they let me in on the idea too many men were involved. I didn’t like to be a squealer and I knew that if I stayed out of the deal and said nothing about it they would go ahead without me and I’d be that much money out without accomplishing anything. I’m not saying this to pass the buck to the others. I suppose that if I had refused to enter the plot and had stood my ground I might have stopped the whole deal. We all share the blame equally. I’m not saying that I double crossed the gamblers, but I had nothing to do with the loss of the world’s series. The breaks just came so that I was not given a chance to do anything toward throwing the game. The records show that I played a pretty good game. I know I missed one terrible fly but, you can believe me or not, I was trying to catch that ball. … I got $5,000. I could have got just about that much by being on the level if the Sox had won the series. And now I’m out of baseball — the only profession I know anything about, and a lot of gamblers have gotten rich. The joke seems to be on us.”59

Some historians view this acknowledgment of bad intentions as an attempt to placate shadowy gamblers.60 Felsch did admit to receiving the $5,000, but not to contributing to the Series loss.

Felsch’s last big-league campaign was much less gratifying than his statistics might indicate. He told Reutlinger, “It’s been hell for me” in dealing with his injured toe and the grand-jury investigation. In addition, the White Sox clubhouse was more divided than ever as some of the “Clean Sox” believed that the Black Sox were accepting money to throw 1920 regular-season games. Felsch denied this in the Evening American interview, but the adverse impact of gamblers on the White Sox could not be disputed.61

The indicted man the Milwaukee Sentinel considered “the best ball player ever produced in Milwaukee” was the object of considerable consternation from his loyal local fans. Some recalled that three days before the 1919 World Series, Felsch instructed his Milwaukee friends to bet on the White Sox. Even after losing three games to the Reds, he still advised his father-in-law to continue wagering on Chicago.62

As 1920 ended, Felsch, Swede Risberg, Buck Weaver, and utility infielder Fred McMullin hired an attorney, Thomas Nash, as they began their fight for reinstatement. Felsch returned to Wisconsin to fish and ponder his future.63 Meanwhile, the owners set the tone for baseball’s future by hiring their first commissioner, stern federal Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis.

Two strikingly different versions of justice were meted out to Happy Felsch and the Black Sox in 1921. Acquitted in court, the players were nevertheless banned forever from Organized Baseball by the newly omnipotent Landis.

Attorney Nash desired a speedy, open trial for his clients and asked Felsch to travel to Chicago on January 31 to file a $10,000 bond to guarantee his appearance.64 Arraignment took place on February 14; due to poorly worded indictments and missing evidence, the initial case was dismissed. At this point, just before spring training, Comiskey hoped to get his talented players back. However, Landis — in his endeavor to clean up baseball and rescue its public image — declared the eight players ineligible. The commissioner knew that his decisions to protect the game would not always favor an individual owner’s interest.65 The decimated 1921 Sox proceeded to finish a dismal seventh.

Through the work of American League President Ban Johnson, enough fresh evidence was secured to support new indictments. Jury trial proceedings began in Chicago on June 27. Judge Hugo Friend decreed that the players could only be convicted for conspiring to defraud the public and injuring the businesses of Comiskey and the American League because there was no law against fixing baseball games. This made the trial of little historical use in determining the truth.66

Felsch’s interview with Reutlinger was disallowed as evidence. Judge Friend said there was so little evidence against Felsch and Weaver that he doubted he could let a guilty jury verdict stand. The trial took place from July 18 to August 2 before packed galleries that supported the encouraged players as slandered heroes rather than wrongdoers.67 Even the accused Felsch appeared jovial as he surprisingly exclaimed, “Hope you win the pennant, boys!” to the Clean Sox clique visiting the courtroom.68 At the end of the trial, the state asked for five-year jail sentences and $2,000 fines. After less than three hours of deliberation, the jury acquitted the players as no state law prohibited throwing games. The Black Sox and the jurors celebrated together at a restaurant.69

The following day, August 3, the party ended as Judge Landis, in his relentless effort to redeem baseball’s credibility, gave this famous edict:

“Regardless of the verdict of juries, no player that throws a ball game; no player that undertakes or promises to throw a ball game; no player that sits in a conference with a bunch of crooked players and gamblers where the ways and means of throwing games are planned and discussed and does not promptly tell his club about it, will ever play professional baseball.”70

The press portrayed the devastated Comiskey as a tragic victim and the Black Sox as aberrant, evil men who betrayed baseball’s purity. In reality, the fix was the culmination of many years of whitewashed baseball corruption.71 It can be claimed that Comiskey self-inflicted his enormous losses with his tight-fisted treatment of players.

Felsch, now 30, was a free and innocent man in the eyes of the law; however, he was forever exiled from the game he loved so much and played so well. Landis’s autocracy held a long reach as he threatened to blacklist anyone who competed with or against the Black Sox. The ban forced the former stars to go vast distances to play baseball.72

In attempts to make money in 1921, Felsch and the seven others formed barnstorming teams in Chicago, northern Indiana, and Wisconsin. Their efforts generally went for naught as ballpark operators and opposing teams were afraid of the consequences of any association with the contaminated Black Sox.73

Felsch endured the death of his father on July 28, adding more unwanted stress during the trial. The 68-year-old carpenter died at home from a cerebral hemorrhage.74 His son was allowed to return to Milwaukee for the funeral; however, Judge Friend demanded Happy’s appearance in court on Monday morning, August 1. Another defense attorney, Ray Cannon, successfully objected, stating that Felsch should be permitted to attend his father’s burial on Monday afternoon.75

Even though his professional career was prematurely over, the tenacious Felsch refused to give up on the diamond or in the legal system in 1922. With a new son, Oscar Ray, born in July, the north-sider set out with the “Ex-Major Leaguers.” This team, which booked nearly 20 games, could boast of athletes including attorney/pitcher Cannon (a former semipro teammate of Felsch) and Black Sox Weaver, Risberg, Cicotte, and Williams. Playing in mostly small towns, the club drew enthusiastic gatherings reaching 3,000 to witness the big-name stars.76

At the same time, Felsch and Risberg sued the White Sox for $100,000 each, declaring that they were ousted from baseball through a conspiracy. Felsch also sought $1,120 in back pay from 1920 and $1,500 for the remainder of a promised 1917 pennant bonus.77 In July Comiskey moved to dismiss the suits for lack of evidence and because of the players’ conspiracy to throw games. He claimed that he paid them in full up until the September 1920 suspensions and denied the 1917 bonus claim.78

The legal proceedings dragged into 1923, when Felsch sued for another $100,000 in damages. He claimed that his “name and reputation has been permanently impaired and destroyed” and that he had “been barred from playing base ball with any professional base ball team in any of the leagues of organized base ball of the United States.” Again, Comiskey requested dismissal of the suits. On June 16 Judge John Gregory dismissed the original $100,000 conspiracy complaint. After much judicial tussling, it was not until 1924 that the case finally went to trial.79

During the protracted battle over his baseball career, Felsch opened a grocery in 1923. Marie and Oscar lived on site for about a year as they attempted to proceed with the stark reality of their new lives.80

In 1924 Milwaukee’s most famous grocer became an accused perjurer and outlaw ballplayer. That January in Milwaukee, Joe Jackson’s suit against Comiskey commenced. Jackson accepted Ray Cannon’s offer of representation in an action similar to Felsch’s and Risberg’s. After turning down a White Sox settlement offer of $2,500, Cannon proceeded in this first Black Sox civil trial. He promised Jackson that Felsch and Risberg would “go the limit for you” in their testimony.81

The trial, well-publicized and heavily attended, provided three weeks of emotional drama. While on the witness stand, a nervous and flustered Felsch denied his signatures on, and knowledge of, his 1920 White Sox contract and related correspondence, mistakenly thinking he was protecting himself. Cannon was taken aback by Felsch’s naīveté, saying, “If it’s your signature, Happy, say so.” Even he could not rescue the ballplayer from perjury charges. “The pride of Milwaukee’s baseball history” was led away to jail in front of an impassive Comiskey and an astonished courtroom. Felsch, who normally “had been a magnet of friendship wherever he happened to move,” stoically looked straight ahead as he departed. Several hours of jail time ensued until friends posted $2,000 cash bond. The bewildered slugger, whose 16 signature denials abruptly suspended the trial, faced arraignment with a potential penalty of two years in a state prison. A handwriting expert confirmed that the 1920 inscriptions matched those that Felsch provided in court and said, “Felsch must be mistaken when he denies it.” Comiskey said he was sorry for his former star “for he was a great baseball player.”82

Judge Gregory called the perjury “malicious and vindictive.” Felsch said he misunderstood the questions and did not intend to perjure himself. The case went to the jury at the end of this tumultuous third week. While the jury was deliberating, Gregory sent Jackson to jail for perjury under $5,000 bond. Gregory overturned the verdict of $16,711 (most of his 1921 and 1922 pay) in favor of Jackson. The sudden, unexplained reappearance of the stolen 1920 confessions caused Gregory to say Jackson’s testimony of game-fixing innocence “reeks with perjury.” Eventually, Jackson, frustrated by his inability to clear his name, settled with Comiskey out of court for a fraction of the verdict, eliminating any appeals. The district attorney dropped the Jackson perjury charges due to insufficient evidence.83

Felsch discovered that playing ball — albeit an outlaw version in south-central Wisconsin — was more fitting and profitable than selling groceries. He was again enjoying what he did best with the Twin City (Sauk City and Prairie du Sac) Red Sox. This small-town club competed with black, Native American, House of David, and other Wisconsin teams unconcerned with the threat of blacklisting by Landis. In addition, Felsch played against fellow Black Sox Weaver (Reedsburg) and Risberg (Minnesota). Thanks to their slugger’s star power and .365 batting average, the 33-20 Red Sox drew crowds as large as 5,000.84

Felsch concluded his skirmishes with the legal system in 1925 and discovered more lucrative, yet distant, playing opportunities. In early February, his perjury case encountered delays, as the district attorney was reluctant to try it.85 Then Felsch’s civil suit against the Sox was settled out of court. This occurred only minutes before the trial was to have finally begun. All of his claims netted Felsch only $1,166 plus interest and costs for a total of about $1,500. The club, claiming that Comiskey was in poor health, did not want to endure another three-week ordeal.86 With criminal accusations hanging over his client’s head, Cannon must have been apprehensive about proceeding with another trial. On May 18 Felsch pleaded guilty to false-swearing, charges that were pending for more than 15 months. Judge Gregory dropped the perjury count and sentenced Felsch to one year of probation.87

Now the 33-year-old was free to play ball. In June he joined Risberg in Scobey, Montana.88 Thus began many years of semipro baseball for Felsch in Montana, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba. Out of the reach of Commissioner Landis, the two Black Sox played before crowded ballparks in Canada and North and South Dakota. Scobey fans adored Felsch for his prodigious home runs, willingness to perform at any position, and jocular personality.89 The pair were each paid a healthy $600 a month plus expenses as they guided their club to a 30-3 record in an environment of heavy gambling and drinking. They often endured opponents’ taunts — and responded with brawling — about their descent from the big leagues to a “cow pasture.”90

Felsch returned home to Teutonia Avenue for the winters.91 Montana baseball lured him back to Scobey for 1926. There he toiled in relative obscurity as the local newspapers gave the fallen star very little ink. In 1927 many small Montana towns, including Scobey, dropped semipro ball in favor of less expensive amateur teams consisting of local players.92

Felsch then elected to play for Regina, Saskatchewan. The opportunity to manage the Balmorals and receive greater publicity in a larger community was very appealing. Utilizing their star’s famed name in advertisements, “Hap Felsch’s Regina Balmorals” began the season on May 25. First baseman Felsch led the way with clutch doubles in the first two games. Competing against other independent semipros from Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta, and North Dakota (including Risberg’s Lignite team), the “Felschmen” were most often victorious. Their manager frequently displayed his awesome home-run power and fielding flexibility (first and third base and pitcher).93

Back home, Felsch’s name was in the papers for a new litigious reason. Late in 1926 Risberg charged 20 ballplayers, including Felsch, with fixing games during the 1917 and 1919 seasons. These allegedly thrown games were intended to alter the final American League standings and the resulting first-, second-, and third-place money. After two days of contentious hearings, Judge Landis exonerated the accused in what some observers described as a quick and convenient whitewash.94

In the summer of 1928, the 37-year-old Felsch returned to Montana. Plentywood, Scobey’s rival, secured Felsch’s services as the semipros competed again in small Montana towns. The acclaimed center fielder joined Plentywood in mid-May for a preseason exhibition tour from Minneapolis back home.95 On Opening Day, May 27, the team lived up to its name, the Plentywood All-Stars, as they crushed Scobey, 20-4. In five at-bats, Felsch hit a double, two triples, and a home run.96 Plentywood played black, House of David, Canadian, Dakota, Minnesota, Iowa, and other eastern Montana clubs. The Sioux City Journal reported that Felsch was one of the greatest throwers ever after he unleashed a peg about 10 feet above the ground from center field into the catcher’s mitt. The one-hopper bounced directly over home plate as “Happy Felsch’s All-Stars” swept an August doubleheader.97

Felsch’s last itinerant years were 1929 and 1930 in Virden, Manitoba. This semipro club also performed against Canadian, Dakota, black, and House of David opponents. In an effort to win more games, Virden signed Felsch in early July, well into the 1929 season. The center fielder supplied power and his famous name to this wheat/railroad town with 1,500 residents.98 Once second baseman Swede Risberg joined the club, the local paper could not contain its glee, stating, “Hap Felsch and his merry men are just about the smoothest all-around combination that has invaded Wesley diamond for a long, long time. Hap has slowed some, but his gardening last night left nothing to be desired.”99 This popular team was closely identified with its star, acquiring the nicknames “Hap Felsch’s Virden All-Stars” and “the Felsch troupe.”100

In 1930 Felsch started out as a headliner with the American-Canadian Clown team. These barnstormers, with their star playing second base, competed against Virden on May 24. By June 6, the Manitoba town reacquired its ex-big leaguer. Felsch finished the 1930 season, his last on the road, with Virden. The potent club employed its center fielder’s name in its advertisements and his bat and glove in its many victories.101 One ad exclaimed, “See the great Hap Felsch spear the fast ones off the top of the fence.”102

In 1931 Felsch stayed out of the public eye. He was still listed in city directories as a ballplayer but his diamond career was essentially over.

A slower Felsch, now 40, returned for one last chance at baseball glory on the Milwaukee sandlots in 1932. Shortly after the Brewers prohibited Felsch’s “contaminated” presence at an all-star game at Borchert Field, Triangle Billiards, an amateur club, gained his services. The newspapers claimed that the team had secured Judge Landis’s permission before adding the former White Sox hero to their roster. Triangle drew much press and a capacity crowd of 15,000 on May 15 to see Felsch patrol center field. Fans exulted in the legend’s return as he exhibited his great skills and familiar gestures of pulling his nose and hat while squinting at the pitcher.

While on the Triangle bench, Felsch entertained several admiring children and smoked cigarettes, displaying his famous grin. One newspaper noted his quiet way, observing that maybe he was thinking that this was “a hell of a place” to be for so illustrious a ballplayer.103 Even though he was considerably past his prime, Felsch continued to play in the area for several more years, shifting to first base as his weight climbed to 200 pounds.104

The Felsch family moved around Milwaukee’s north side an extraordinary number of times in Happy’s post-baseball years. These were often efforts to obtain a new saloon location. During the Prohibition year of 1932, the family opened a new soft-drink parlor and lived at the site.105 In 1933 the family moved again and lived near their latest tavern as Prohibition ended. The business shifted north in 1936. By 1938, the family had again relocated their tavern and residence further northward.106

The notable former big leaguer did his best to remain cordial with his patrons. The Milwaukee Journal reported:

“In the mid-thirties Felsch’s tavern on W. Center St. became a gathering place for sand lot players and managers. Happy served free peanuts and kept the bowls on the bar full. The crunch of shells underfoot mingled with baseball talk that often lasted far into the night. Occasionally, a customer would try to draw Felsch into a comparison of the top players of the 1930s with those he had served with in the majors. Happy refused to comment. He seldom became angry when questioned — even about the Black Sox scandal — but found that silence was most effective in ending a distasteful subject.”107

The 1940s began with Oscar and Marie operating the Barn Grove Tavern. By 1943, Happy had left the saloon business, relocated closer to town, and worked as an assembler and watchman. The family moved again in 1947, only several blocks north of Borchert Field, the site of Felsch’s successes more than 30 years earlier.

By 1949, Happy had begun his final career as a crane operator. In 1952 he and Marie, parents of three and eventual grandparents of 11, ended their somewhat nomadic existence as they entered their final home on the second floor of a flat at 2460 N. 49th Street. At this location, Eight Men Out author Eliot Asinof and sportswriter Westbrook Pegler conducted their pivotal interviews with Felsch.

In 1962 Felsch, over 70 years old, retired as a crane operator for the George Meyer Company. His family adoringly remembered him as “always in a good mood.” Card playing, bowling, hunting, fishing, smoking, and coffee drinking were his favorite pastimes when he was not listening to the Milwaukee Braves on the radio.108

Judge Terence Evans recalled playing ball as a child in Garfield Park (now Rose Park) at Fifth and Burleigh. During this time in the late 1940s and early 1950s, Felsch would often observe Evans and his friends on the diamond. The children called him “Happy” and would converse with the local legend frequently. Evans did notice that Felsch, in poor physical condition, held one arm in a peculiar fashion, as if he had suffered a slight stroke.109

The north side’s finest ballplayer succumbed to a coronary blood clot due to arteriosclerosis on August 17, 1964, at Milwaukee’s St. Francis Hospital. The 73-year-old suffered from varicose veins and a leg abscess for years, but was not seriously ill until six months before his death. Diabetes, a liver ailment, and a pancreatic tumor also complicated his health.

Felsch was survived by his wife, son, and two daughters. The funeral was held on August 20 at the Franzen, Jung and Kaufmann Funeral Home, with entombment in “The Gardens of the Last Supper” at Wisconsin Memorial Park in the northwestern suburb of Brookfield.110

If not for the Black Sox Scandal, Happy Felsch might be remembered as one of the best all-around center fielders in baseball history. His superb skills induced reporters and managers of his era to compare him favorably with future Hall of Famers. Philadelphia Athletics manager Connie Mack referred to Happy as “the greatest all around fielder in the country today, not barring Tris Speaker and Ty Cobb.”111 Cobb himself proclaimed, “Hap Felsch was a wonder.”112 None other than Babe Ruth ranked the pride of Milwaukee as the best center fielder of his era, asserting, “I would rate Hap Felsch of the old White Sox and Tris Speaker far superior to Cobb on the defense. Felsch was a greater ball hawk than Speaker, and what an arm he had!”113

Happy Felsch gave his side of the story in several interviews. Thanks to groundbreaking conversations with Felsch, writers including Asinof, Pegler, and Reutlinger were able to shed some light on the Black Sox Scandal. Most of the other fix participants were either too ashamed or fearful of gangster retribution to speak on the record. Major-league baseball preferred to keep the embarrassment of 1919 out of the public eye. Even in 1959, Commissioner Ford Frick persuaded a major television network to cancel a dramatization of the Black Sox scandal, stating that it would be bad for baseball and, therefore, bad for America.114

The amiable Felsch, however, did speak his piece in the last years of his life. Asinof was so appreciative of the center fielder’s openness that he dedicated his book, Bleeding Between the Lines, to the memory of Felsch.115 In this 1979 work, Asinof recounts his interview of Felsch for Eight Men Out, his 1963 chronicle of the scandal. The former minor leaguer first started his detailed research in 1960 when only four of the eight Black Sox were still alive. Cicotte, Gandil, and Risberg either refused or stonewalled Asinof’s inquiries.116 Felsch became his primary source.117

During his research, Asinof visited Milwaukee in an attempt to interview the ailing Felsch. Even after receiving repeated phone calls and a letter, the protective Marie continued to turn down the author. Asinof finally mustered enough courage to visit their home only after a man he met in a bar, who had been acquainted with Felsch, described him as a “real good guy” that everybody liked.

Marie relented when the polite yet persistent Asinof appeared at her door with a bottle of scotch to share with Happy, as Reutlinger did in 1920. She led him to the dark upstairs sitting room, asked for kindness in his questioning, and allowed the two men to spend the afternoon in conversation. Asinof detected hurt, guilt, and remorse in Felsch’s voice as he said, “I shoulda knew better. I just didn’t have the sense I was born with. It matters. It still matters.”118

With his heavily bandaged foot resting on an ottoman, the ruddy-faced Felsch opened up to Asinof. He was pleased to talk baseball and recounted his early days as Milwaukee’s baseball prodigy. The 70-year-old vividly recalled his underprivileged childhood, saying, “Seems like all I ever wanted was to hit a new ball with a new bat.”

Asinof described Felsch as a fine storyteller who was humble and amusing. He did express great contempt for the penny-pinching Comiskey and his fawning sportswriters. Regarding the scandal, he told Asinof, “It was a crazy time. I don’t know how it happened, but it did, all right.” He went on to say, “God damn, I was dumb, all right. Old Gandil was smart and the rest of us was dumb.” Felsch also recollected the times he was pressured by menacing gamblers into committing misplays in local leagues, the 1919 World Series, and the 1920 season.119

For his series of Black Sox articles in 1956, writer Westbrook Pegler also called on Felsch at his home, expecting to be refused. Instead, he was warmly received. After telling Pegler that an abscessed varicose vein near his right ankle kept him from sleeping more than four hours a night, Felsch recounted his careers as a tavern owner and crane operator. He explained how argumentative drinkers and a tire-slashing incident prompted the family to finally sell a business as public as a saloon. After quickly spending too much of the tavern’s proceeds, Happy told Pegler, “I gotta cut that out” and began the crane job. The former star went on to assert that Buck Weaver, who played very well in the 1919 Series, was unfairly banned. Felsch did not admit to any guilt and stated that his Series statistics were poor due to fine plays by the Reds.120

Asinof, in a 1999 interview, was convinced that Felsch was willing to talk more openly in the 1960s as his illnesses and impending death made him unafraid of vengeful gamblers. During the three-hour interview in the stale, dingy sickroom, Asinof found the uneducated retiree to be charming and articulate. Felsch actually wanted the author to stay longer as the conversation appeared to be liberating for him.121 Pegler and Reutlinger did not experience this advantageous passing of time. Felsch could finally be forthright about the disastrous influence gambling had upon the Black Sox, baseball, and his own life.

An updated version of this biography appears in “Scandal on the South Side: The 1919 Chicago White Sox” (SABR, 2015), edited by Jacob Pomrenke.

Notes

1 Telephone interview with Milwaukee historian John Gurda, November 5, 1999.

2 Felsch’s Application for Social Security Account Number, December 3, 1943; Wisconsin Original Certificate of Death #’64 024373; and 1900 and 1930 United States Censuses.

3 1891 Milwaukee City Directory.

4 1900 US Census; The Sporting News, August 29, 1964; Steven A. Reiss, Touching Base: Professional Baseball and American Culture in the Progressive Era (Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1999), 176; Richard Lindberg, The White Sox Encyclopedia (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1997), 149.

5 1907-1909 Milwaukee City Directories; Eliot Asinof, Eight Men Out (New York: Henry Holt, 1963), 53-4.

6 Reiss, 177; Milwaukee Journal, October 7, 1917; Milwaukee Journal, August 18, 1964.

7 Lindberg, 149; Joseph L. Reichler, ed., The Baseball Encyclopedia (New York: Macmillan, 1985), 906; “Felsch Eager …”; David Neft and Richard Cohen, The Sports Encyclopedia: Baseball (New York: St. Martin’s Press), 97.

8 1911 Milwaukee City Directory; Milwaukee Sentinel, July 17, August 7, and September 17, 1911; Milwaukee Journal, April 8 and June 11, 1911.

9 Milwaukee Sentinel, June 12 and July 8 and 21, 1912; Manitowoc (Wisconsin) Daily Herald, June 15 and 17 and July 1 and 8, 1912.

10 Asinof, 53; Milwaukee Sentinel, June 12, 1912; “Felsch Eager . . .” and “Hap Felsch, Idol of Sox, Wanted to Be Wrestler,” unidentified 1917 newspaper articles from the National Baseball Hall of Fame Felsch Clippings File.

11 Milwaukee Sentinel, April 30 and May 1, 1913.

12 Milwaukee Sentinel, June 26-30, 1913, Milwaukee Journal, August 9, 1914; Lloyd Johnson and Miles Wolff, eds., The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, 2nd Edition (Durham, North Carolina: Baseball America, 1997), 189.

13 Milwaukee Journal, August 9, 1914.

14 Milwaukee Journal, August 7-11, 17-19, 1913; Marshall D. Wright, The American Association (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 1997), 67-68.

15 Wright, 73-74; Milwaukee Journal, August 9, 1914.

16 Asinof, 54; Milwaukee Journal, August 7-9, 1914, and February 24, 1941.

17 Milwaukee Sentinel, April 15, 1915.

18 Lindberg, 21-22; “Felsch Eager . . .”

19 1915 Milwaukee City Directory; Eliot Asinof, Bleeding Between the Lines (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston: 1979), 79; Milwaukee County Marriage Records, 1915, vol. 256, 320; Milwaukee Journal and Milwaukee Sentinel, October 1915; telephone interviews with Milwaukee historians John Gurda and Harry Anderson, November 5, 1999.

20 Milwaukee Journal, October 29, 1915; Milwaukee Sentinel, October 29, 1915.

21 Warren Brown, The Chicago White Sox (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1952), 68; Lindberg, 23.

22 Asinof, Eight Men Out, 180; Robert C. Cottrell, Blackball, the Black Sox, and the Babe: Baseball’s Crucial 1920 Season (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2002), 51; John Thorn, Pete Palmer, and Michael Gershman, eds., Total Baseball, Seventh Edition (Kingston, New York: Total Sports Publishing, 2001), 762 and 2117.

23 G.W. Axelson, Commy: The Life Story of Charles A. Comiskey (Chicago: The Reilly & Lee Co., 1919), 204-205; Frommer, 70, 76-77; Lindberg, The White Sox Encyclopedia, 434; Joseph P. Murphy, Jr., “Pants Rowland: The Busher from Dubuque,” Baseball Research Journal #24, 118-119; 1924 Joe Jackson Milwaukee trial transcripts, #64442 Circuit Court Bill of Exceptions, Volume 3, 1566-1588.

24 Milwaukee Journal, October 7, 10, and 25, 1917.

25 Milwaukee Journal, October 8 and 10, 1917.

26 Thorn, Third Edition, 355.

27 Milwaukee Journal, October 14, 16, 17, 18, 23, 24, and 25, 1917; Milwaukee Sentinel, October 21 and 24, 1917; and Felsch/Sox 1917-1919 contract, Chicago White Sox Hall of Fame, Comiskey Park, Chicago.

28 Koppett, 128-129.

29 Milwaukee Sentinel, March 18 and 19, 1918; Frommer, 80-83.

30 Milwaukee Sentinel, May 10-21, 1918.

31 Milwaukee Sentinel, July 2-3, 1918; Felsch/Sox 1917-1919 contract.

32 Milwaukee Sentinel, July 2-4, 14, 18, 1918.

33 Cottrell, 82, 83, 287; The Sporting News, January 9, 1919.

34 Milwaukee Sentinel, July 5 to October 14, 1918.

35 Brown, 82-83, Daniel E. Ginsburg, The Fix Is In: A History of Baseball Gambling and Game Fixing Scandals (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 1995), 110; Koppett, 129 Murphy, 119.

36 Neft, 97; W.A. Phelon, “Closing Events of 1918 Baseball Season,” Baseball Magazine, October 1918, 483, 500, 501; Harold and Dorothy Seymour, Baseball: The Golden Age (New York: Oxford University Press: 1971), 250-251.

37 Lindberg, Sox: The Complete Record . . . , 62; “The Return of the Prodigals,” The Sporting News, January 2 and 23, 1919.

38 Baseball-almanac.com/rb_ofas.shtml; Baseball-almanac.com/rb_ofdp.shtml.

39 Frommer, 85-91, Seymour, 255; Stein, 131 and 142-143.

40 Eliot Asinof, 1919: America’s Loss of Innocence, (New York: Donald I. Fine, 1990), 301 and 325; Ginsburg, 91-93 and 100 Edward G. White, Creating the National Pastime: Baseball Transforms Itself, 1903-1953 (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1996), 86.

41 Bob Hoie, “1919 Baseball Salaries and the Mythically Underpaid Chicago White Sox,” Base Ball: A Journal of the Early Game (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co.), Spring 2012.

42 Asinof, Eight Men Out, 54; Frommer, 86; Reiss, 43, 52, 93, 171-172; Stein, 158.

43 Reichler, 906.

44 Brown, 87-105; Stein, 164-186.

45 Milwaukee Sentinel, October 3-18, 1919.

46 Asinof, Eight Men Out, 129-131; Stein, 194; Milwaukee Sentinel, October 11 and 13, 1919.

47 Asinof, Eight Men Out, 123-124.

48 Reiss, 94.

49 Telephone interview with Steve Christie of the Hupmobile Club, Inc., November 10, 1999; Ed Linn and Bill Veeck, The Hustler’s Handbook (Durham, North Carolina: Baseball America, 1996), 225; 1924 Jackson trial transcripts.

50 Asinof, Eight Men Out, 131.

51 1924 Jackson trial transcripts.

52 Reiss, 94.

53 Thorn, Third Edition, 831 and 1965.

54 Koppett, 139.

55 Axelson, 203-204; Bill James, The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract (New York: The Free Press, 2001), 765; Lindberg, Sox: The Complete Record …, 64.

56 Frommer, 125; Milwaukee Sentinel, October 11, 1920.

57 Asinof, Eight Men Out, 168, 169, and 175; Gropman, 185; Koppett, 140-145; Milwaukee Sentinel, September 27-28, 1920; Seymour, 303.

58 Asinof, Eight Men Out, 188-193.

59 Chicago Evening American, September 30, 1920.

60 Victor Luhrs, The Great Baseball Mystery: The 1919 World Series (South Brunswick, New Jersey: A.S. Barnes, 1966), 184 and 250; Seymour, 333.

61 Eliot Asinof, Bleeding, 92-94; Asinof, Eight Men Out, 144-148, 160, and 190-191; Chicago Evening American, September 30, 1920.

62 Milwaukee Sentinel, September 28 and 30, 1920.

63 Milwaukee Sentinel, October 4, 1920.

64 Milwaukee Sentinel, February 1, 1921.

65 Ginsburg, 142-3; David Pietrusza, Judge and Jury: The Life and Times of Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis (South Bend, Indiana: Diamond Communications, 1998), 176-7, and 186; White, 104.

66 Ginsburg, 142-4; Milwaukee Journal, July 19, 1921; Rader, 105.

67 Asinof, Eight Men Out, 240; Ginsburg, 142-4.

68 Asinof, Eight Men Out, 242.

69 Milwaukee Journal, July 29, 1921; Rader, 105; Stein, 270-1.

70 Seymour, 330.

71 Asinof, Eight Men Out, 202; Koppett, 101-2.

72 Seymour, 330.

73 Cottrell, 253; Milwaukee Sentinel, August 7, 1921; Stein, 265.

74 Milwaukee County Death Records, 1921, vol. 458, 140.

75 Milwaukee Sentinel, July 31, 1921.

76 Milwaukee County Birth Records, 1922, vol. 811, 130; Milwaukee Journal, October 3, 1988; Milwaukee Sentinel, June 23, and 25, 1922; 1922 Milwaukee City Directory.

77 Felsch vs. American League Baseball Club of Chicago causes of action (Milwaukee County Circuit Court, June 21, 1922); and Milwaukee Sentinel, June 21, 1922.

78 Felsch vs. American League Baseball Club of Chicago answer (Milwaukee County Circuit Court, July 28, 1922); Milwaukee Sentinel, July 28, 1922.

79 Felsch vs. American League Baseball Club of Chicago amended complaint and answer (Milwaukee County Circuit Court, April 2, 1923); Milwaukee Journal, May 18, 1939; Milwaukee Sentinel, June 16, 1923.

80 1923 Milwaukee City Directory.

81 Ray Cannon, Letter to Joe Jackson, January 11, 1924, 1924 Joe Jackson Milwaukee trial papers, Milwaukee County Historical Society, Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

82 Anderson interview; Gurda interview; Milwaukee Sentinel, February 11-14, 1924.

83 Asinof, Eight Men Out, 289-292; Ginsburg, 155; Gropman, 220-7 and 302; Milwaukee Sentinel, February 14, 15, and 21, 1924 Milwaukee Journal, March 13, 1966.

84 Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, June 21, 1998; Stephen J. Rundio III, From Black Sox to Sauk Sox 1924 (Cleveland: Society for American Baseball Research, 1997), 1-8.

85 Milwaukee Journal, February 5, 1925; Ray Cannon, Letter to Joe Jackson, August 11, 1924, 1924 Joe Jackson Milwaukee trial papers, Milwaukee County Historical Society, Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

86 Milwaukee Journal, February 9, 1925; Milwaukee Sentinel, February 10, 1925.

87 Milwaukee Sentinel, May 19, 1925.

88 Plentywood (Montana) Herald, June 19, 1925.

89 Daniels County (Montana) Leader, August 20, 1925.

90 Gary Lucht, “Scobey’s Touring Pros: Wheat, Baseball and Illicit Booze,” Montana the Magazine of Western History, Summer 1970, 88-93.

91 1923-1927 Milwaukee City Directories.

92 Plentywood Herald, June 4, 1926, and April 22, 1927.

93 Regina (Saskatchewan) Morning Leader, May 18 to August 23, 1927.

94 Pietrusza, 296-302.

95 Plentywood Herald, May 18, 1928.

96 Plentywood Herald, June 1, 1928.

97 Plentywood Herald, June 8 to August 16, 1928.

98 Virden (Manitoba) Empire-Advance, May 14 to July 23, 1929.

99 Virden Empire-Advance, July 23, 1929.

100 Virden Empire-Advance, August 6, 1929.

101 Virden Empire-Advance, May 6 to August 19, 1930.

102 Virden Empire-Advance, July 8, 1930.

103 Milwaukee Journal, May 8, 15, 16, 21, and 22, 1932; Milwaukee Sentinel, May 21 and 23, 1932; Virden Empire-Advance, May 25, 1932.

104 Milwaukee Journal, August 18, 1964; New York World Telegram, July 27, 1937.

105 1932 Milwaukee City Directory.

106 1933-1939 Milwaukee City Directories.

107 Milwaukee Journal, August 18, 1964.

108 Asinof, Bleeding, 89; Asinof, Eight Men Out, 284; Milwaukee Journal, August 18, 1964; Milwaukee Sentinel, September 25, 1956; personal interviews with Felsch’s son and daughter-in-law, Oscar R. and Ruth Felsch and Felsch’s granddaughters, Kathy Repka and Laura Laurishke, February 9, 2001; 1940-1965 Milwaukee City Directories; 1943-1957 Milwaukee Phone Books.

109 Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, November 18, 2001; telephone interview with U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals Judge Terence T. Evans, May 11, 1999.

110 Wisconsin Original Certificate of Death #’64 024373; Milwaukee Journal, August 18, 1964.

111 Milwaukee Leader, August 12, 1916; Charles Einstein, ed., The Third Fireside Book of Baseball (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1968), 133.

112 Stein, 312.

113 Allison Danzig and Joe Reichler, The History of Baseball (Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, 1959), 175.

114 Asinof, 1919, 345; Paul Green, “The Later Lives of the Banished Sox,” Sports Collectors Digest, April 22, 1988, 196-7.

115 Asinof, Bleeding, dedication page.

116 Asinof, Bleeding, 58-64 and 85-92.

117 Ginsburg, 160-1.

118 Asinof, Bleeding, 79, 89, 90, and 113.

119 Asinof, Bleeding, 113-118.

120 Milwaukee Sentinel, September 25, 1956.

121 Telephone interview with Eliot Asinof, November 5, 1999.

Full Name

Oscar Emil Felsch

Born

April 7, 1891 at Milwaukee, WI (USA)

Died

August 17, 1964 at Milwaukee, WI (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.