August 31, 1935: In first full season, Vern Kennedy throws no-hitter for White Sox

The Chicago White Sox were in unusual territory. Not since the days of Hall of Fame player-manager Eddie Collins had the Pale Hose sported at least a .500 record on the last day of August; however, Jimmy Dykes, in his first full season as player-manager, had the fifth-place White Sox (61-60) in position for their first winning season in nine years as they took on the Cleveland Indians for a two-game series to conclude a 24-game homestand.

The Chicago White Sox were in unusual territory. Not since the days of Hall of Fame player-manager Eddie Collins had the Pale Hose sported at least a .500 record on the last day of August; however, Jimmy Dykes, in his first full season as player-manager, had the fifth-place White Sox (61-60) in position for their first winning season in nine years as they took on the Cleveland Indians for a two-game series to conclude a 24-game homestand.

The Sox had struggled during their extended stretch in Comiskey Park, having won just nine of their last 22 games. And to make matters worse, they were coming off an embarrassing 6-2 loss in an exhibition game to the Milwaukee Brewers of the American Association at Milwaukee’s Borchert Field the day before.1 The third-place Tribe, on the other hand, was playing its best ball of the campaign under Steve O’Neill, who had replaced manager Walter Johnson on August 5. He had guided the team to 18 wins in its last 28 games to move into third place (64-58), though well behind the streaking Detroit Tigers. The Indians had just concluded a 20-game homestand and were scheduled to play 20 of their next 22 games on the road.

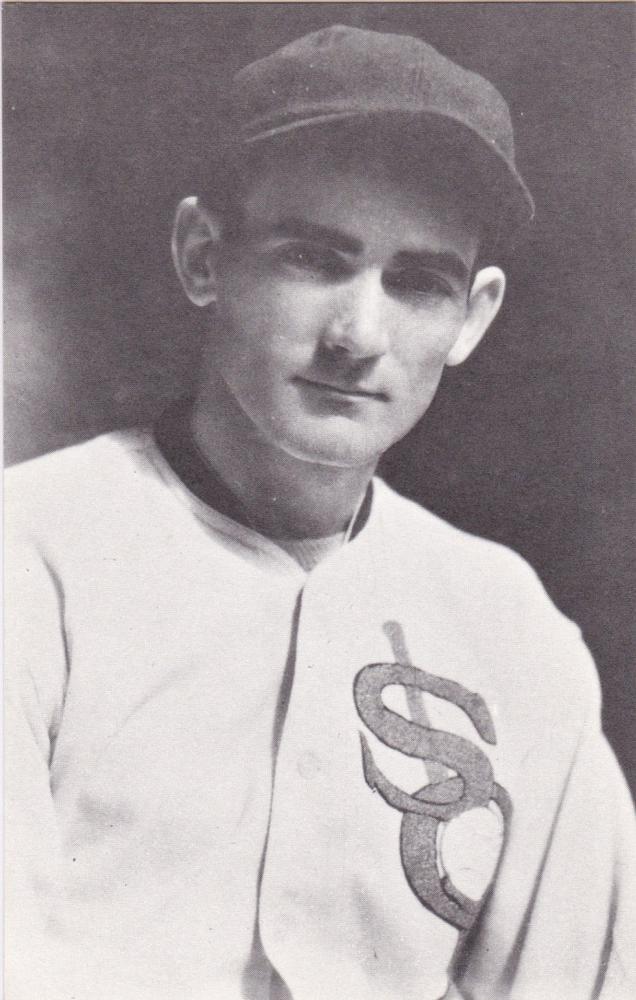

Toeing the rubber for the White Sox was 28-year-old right-hander Vern Kennedy, in his first full season in the big leagues. A former decathlete, Kennedy was hailed by his onetime coach Tad Reid as “the greatest athlete ever produced” by Central Missouri Teachers College (now known as the University of Central Missouri, in Warrensburg), but chose the ball and glove instead of a classroom.2 He began his professional baseball career in 1930, failed in subsequent look-sees with the Pittsburgh Pirates and the Philadelphia Athletics, and was acquired by the White Sox in 1934 after going 15-18 and 17-18 in 1933 and 1934, respectively, for the Class-A Oklahoma City Indians of the Texas League. One of the biggest surprises on the Chisox in 1935, Kennedy had completed eight of his last nine starts and sported a 9-7 slate (4.11 ERA). On the mound for the Indians was a longtime reliable right-hander, 29-year-old Willis Hudlin, who had tossed one of the best games in his career in his last appearance, a 15-inning shutout of the Philadelphia A’s on August 24 to improve his record to 12-9 and 122-114 in parts of 10 seasons, all with the Indians.

The weather was perfect with clear skies and temperatures around 70 degrees for a Saturday afternoon of baseball at the Base Ball Palace of the World on the South Side of the Windy City. After a one-two-three first, Kennedy got the only run he needed in the bottom of the frame. Jocko Conlan led off with a single and then scored on Luke Appling’s two-out single.

The White Sox scored four more runs in the game, but they were just gravy given Kennedy’s gem. In the fourth, Dykes’s one-out single drove home Zeke Bonura, who had doubled. George Washington followed with another single, but Luke Sewell hit into inning-ending 6-4-3 twin killing. The most exciting play of the game took place in the sixth. Hudlin loaded the bases on singles to Bonura and Dykes and a walk to Sewell with two outs. Kennedy, a competent hitter, spanked a liner that rolled all the way to the wall in center field, clearing the bases for a 5-0 lead. (Kennedy batted .244 in his 12-year career.)

Kennedy “sent a sinking assortment of curves, snow balls and dazzlers across the plate,” gushed the United Press.3 At no time was the hurler in trouble and his teammates played flawless, error-free defense. The first Indians baserunner was Eddie Phillips, who led off the third with a walk. He was forced by the next batter Roy Hughes, who subsequently stole second, the only time in the game that a Tribe player advanced that far. Kennedy also issued a walk in the sixth and one in the seventh.

Kennedy began the ninth three outs away from becoming the third White Sox hurler to toss a no-hitter in Comiskey Park. The immortal Ed Walsh tossed the first, turning the trick on August 27, 1911, against the Boston Red Sox in the 14-month-old park, known then as White Sox Park. Joe Benz was the second, on May 31, 1914, beating the Indians, 6-1. Kennedy fanned Kit Carson, pinch-hitting for Hudlin, for the first out. To the plate stepped streaking Milt Galatzer, who began the day batting .393 (22-for-56) in his last 16 games to raise his season average to .317. In what sportswriter Edward Burns of the Chicago Tribune called the only “hair raiser” of the game, Galatzer hit a ball to short left.4 “It looked like a certain hit,” continued Burns. Rip Radcliff had had started every game thus far in left field, but was out with an injury (and eventually missed six games). In his place was center fielder Al Simmons, who had considerable experience in left field when he played for the A’s. Bucketfoot Al made a “diving catch,” wrote Burns, to save the no-no. Perhaps shaken from the only close play of the game, Kennedy issued his fourth and final walk of the game, to Earl Averill. Only Joe Vosmik, who entered the game as the AL’s leading hitter (.352 batting average), stood between Kennedy and baseball immortality. On a 3-and-1 count, Vosmik hit a screeching liner down the right-field foul line, but it was “foul by a foot,” declared Burns. On the next pitch, Kennedy caught Vosmik looking to record his fifth and final punchout and secure the no-hitter in 1 hour and 41 minutes.

Kennedy’s no-no was the first in the AL since Bobby Burke held the Boston Red Sox hitless on August 8, 1931. Paul Dean of the St. Louis Cardinals fashioned the last one in the big leagues, defeating the Brooklyn Dodgers, 3-0, on September 21, 1934. (There weren’t any no-hitters in the majors in 1932 or 1933.) Kennedy struggled in his next five starts, going 0-4 with a 5.08 ERA in 33⅔ innings, and finished the season with an 11-11 slate (3.91 ERA in 211⅔ innings). He won a career-best 21 games the next season and earned his first of two All-Star berths. Kennedy never achieved the stardom that that season might have predicted, nor flirted again with a no-hitter. Three seasons later, he led the AL with 20 losses, splitting his time with the Detroit Tigers and St. Louis Browns. In parts of 12 major-league seasons with seven teams, he posted a 104-132 record.

Like Kennedy, the White Sox slumped in September, doomed by an 8-17 skid to finish in fifth place with a 74-78 record. The next season, led by Kennedy, Dykes’s squad not only had a winning record (81-70), the fourth-place club also finished in the first division for the first time since 1920, a year marked by the lifetime ban of eight White Sox players implicated in the 1919 World Series betting scandal.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also accessed Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, SABR.org, and The Sporting News archive via Paper of Record.

Notes

1 Charles Nevada, “White Sox Lose Exhibition at Milwaukee, 6-2,” Chicago Tribune, August 31, 1935: 15.

2 United Press, “Kennedy’s Old Coach Hails Him as Star Athelte,” Chicago Tribune, September 1, 1935: A3.

3 United Press, “Vernon Kennedy Pitches No-Hit, No-Run Game for Chisox,” Arizona Republic (Phoenix), September 1, 1935: 12.

4 Edward Burns, “Kennedy Pitches No-Hit Game for White Sox,” Chicago Tribune, September 1, 1935: A3.

Additional Stats

Chicago White Sox 5

Cleveland Indians 0

Comiskey Park

Chicago, IL

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.