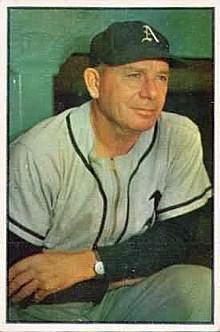

Jimmy Dykes

One of the best-known figures of major league baseball in the middle of the 20th century, Jimmy Dykes was a fixture in American League dugouts during a career that spanned more than 40 years. His major league experiences began with Connie Mack and ended with Charles O. Finley-no greater contrast in baseball characters can be imagined! In all, he managed six teams in the majors and one in the minors and had five big league coaching jobs. Dykes saw it all and shared his knowledge with three generations of big-league ballplayers and personalities.

One of the best-known figures of major league baseball in the middle of the 20th century, Jimmy Dykes was a fixture in American League dugouts during a career that spanned more than 40 years. His major league experiences began with Connie Mack and ended with Charles O. Finley-no greater contrast in baseball characters can be imagined! In all, he managed six teams in the majors and one in the minors and had five big league coaching jobs. Dykes saw it all and shared his knowledge with three generations of big-league ballplayers and personalities.

James Joseph Dykes was born in a hotbed of baseball, Philadelphia, on November 10, 1896. Not a large man for the day, standing 5-foot-9 and weighing 185 pounds at most, he developed strong wrists from working as a pipefitter, and as a caddie at Merion Cricket Club. Gravitating toward the sandlots as did so many other Philadelphia-area boys of the era, Dykes signed to play second base for the Gettysburg team in the Class D Blue Ridge League. The Gettysburg club lost money that year, allegedly not meeting payroll for two months. Dykes contended later that some of the better players on his team traveled to other league clubs to play under an alias for a game or two, just to earn a few extra dollars on the spot. Such a practice ended quickly when opposing managers recognized such players.

It was there at Gettysburg that Connie Mack of the Philadelphia Athletics spotted him, and Jimmy signed with the American League entry of his hometown. Dykes made his big-league debut May 6, 1918, after A’s regular second baseman Maury Shannon was drafted into the Army for World War I. Playing in 76 games in the 1918 and 1919 seasons, Dykes demonstrated the proverbial “good field-no hit” stereotype, compensating for his inability to hit even .200 against wartime pitching with his graceful fielding around second base. His lack of hitting could be attributed to the fact that he was promoted from a Class D league straight to the majors, and really needed more seasoning. Also, Dykes did a tour of duty with the Army after the 1918 season and was not in shape when the next season rolled around. Nonetheless, his poor hitting earned a demotion to the Atlanta Crackers of the Southern Association during the 1919 season.

By the end of spring training in 1920, however, Dykes had become the Athletics’ regular at second base, and his sturdy fielding the next two years solidified his place in the lineup. In 1921, he led the league’s second basemen in putouts, assists and errors, and he played more games than any other American Leaguer. His batting improved to the point that he was becoming an effective member of the lineup.

Just before the 1922 season, Mack saw the opportunity to improve his ball club when Detroit asked waivers on their starting second baseman, Ralph Young, who had just missed hitting .300 the previous season. Mack put in his claim and moved Dykes to third base. As the team improved each year in the 1920s, Dykes often filled in at second base and then at shortstop as Mack juggled his lineup to play all his infielders. Max Bishop would eventually replace Young at second base, Chick Galloway was the shortstop, and Sammy Hale was the primary third baseman. But Dykes could play them all and filled in as necessary. His fielding continued to shine. When first baseman Joe Hauser was injured prior to the 1927 season, Dykes was the logical choice to fill in.

His offense also improved, topping .300 five times between 1924 and 1930, despite hitting near the bottom in the batting order, usually seventh or even eighth. But his versatility became legend. He played eight different positions in 1927. Dykes even pitched in relief in two games. His popularity was high, as evidenced by his gift for being named team MVP in 1924-a new Flint sedan.

Mack’s team culminated its climb to success with three consecutive pennants, 1929-31, and two World Series titles. Wearing uniform number 5, Dykes played an integral part in their success. His two hits in the seventh inning of Game Four were pivotal in the A’s winning the 1929 World Series. He ended the Series with a .421 batting average and 4 RBIs. In 1930, he helped the A’s repeat as World Champions by slamming four extra-base hits during the Series.

Now in his thirties, Dykes played fewer games in the middle infield and more at the hot corner. In 1932, he led the league at that position with a .980 fielding percentage. However, as the A’s completed their season by finishing a distant second by 13 games, Mack faced a serious financial bind. The Depression affected attendance, and the neighboring Phillies of the National League always had a solid following. Desperate for cash to maintain operations, Mack made a stunning decision at the end of the season that sealed the fate of his club as a pennant contender. On September 28, he dealt three stars of his team (Dykes, Al Simmons and Mule Haas) to the Chicago White Sox-not in a trade for other players, but instead for the princely sum of $100,000! Breaking up the heart of his team effectively ended the Athletics’ on-field success for decades to come, but it did keep them solvent.

Chicago was truly a bad team. Despite future Hall of Famer Luke Appling holding forth at shortstop, and Ted Lyons and Sad Sam Jones toiling on the pitching mound, the Windy City’s entry in the American League had little else prior to this acquisition. Settling into his new home, Dykes led the league’s third basemen with 296 assists in his first season in the Midwest.

Dykes was selected to play third base in the inaugural All-Star game in 1933, which was played in the White Sox’ home field of Comiskey Park. Batting in the sixth position in the lineup, Dykes went 2-for-3 in the game, plus a base on balls, and scored a run as the American League won the inaugural event, 4-2. He was selected as a backup for the 1934 game, but did not play.

As time moved on, White Sox owner Charlie Comiskey grew frustrated with the losses and decided that a managerial change might shake things up. When the 1934 team stumbled out of the gate, winning only four of its first 15 games, he fired Lew Fonseca and installed Dykes as player-manager. The team did not improve too much that season, still finishing dead last, but Dykes maintained Comiskey’s confidence as an on-field leader.

By 1937, Dykes decided that his advanced age (39) precluded his continued use as a starter. He still filled in for infielders as conditions warranted during the next two seasons. His last active duty was two third-base appearances in 1939. Thus closed the book on a playing career of nearly 2,300 games, more than 8,000 at bats, over 1,100 runs scored, and 1,000 runs batted in, a .280 career batting average, and a slugging percentage of nearly .400. He led the league in games played in 1921, ranking among the leaders in that category 1932 and 1933 (at age 36, no less). All in all, very impressive numbers for a solid all-around infielder in any era.

As Chicago’s manager, Dykes succeeded in coaxing more productivity out of his players. From 1936 through 1941, the Sox had only one losing season, reversing a trend that had seen only three winners since their pennant-winning season of 1919. Winning became a habit of this team in the pre-World War II era, and Dykes commented on the good times with his humorous remark, “When you’re winning, beer tastes better.”

A colorful member of the team was Zeke Bonura, a slugger stationed at first base who was not known for either high intellect or fielding grace. Zeke had a problem understanding signs-Dykes recalled that one game got him so flustered that he yelled out, “Bunt, you meathead. Bunt! Bunt! B-U-N-T.” It didn’t work-no bunt from Zeke that day.

After Zeke was traded to Washington in 1938, Dykes did not bother to change the signs because Bonura couldn’t remember them anyway. Nevertheless, a surprise was in store when the teams did meet that season. After Zeke advanced to third base, he saw Dykes in the dugout swat at a mosquito. Recalling (for once in his career) that a swat meant a steal, Bonura took off for home, knocked the ball away from the catcher, and scored. Considering that he stole only 19 bases in his career, this was quite a shocking event! Bonura explained later, “I saw Dykes give the sign to steal, but forgot I wasn’t on his team anymore.” (Francis)

One of the innovative ideas Jimmy implemented in 1939 involved Ted Lyons, a popular pitcher with the fans who always drew big crowds. Now in his seventeenth season with the Sox, Ted’s arm was wearing out as he approached his fortieth birthday. Jimmy’s solution was to schedule Ted to pitch once a week, Sundays only, to save his arm and draw fans. It worked, as Ted had one of his better years, leading the league in two categories: lowest opponents’ on-base percentage and lowest WHIP-walks plus hits per inning pitched. During the four years that Lyons pitched in his reduced schedule, he won 52 games. In 1942 he led the league in earned run average (2.10) and completed each of his 20 starts.

Dykes provided a footnote to the efforts to integrate major league baseball. In March 1938, the White Sox played a benefit exhibition against the Pasadena Sox, a group of young players from that California city. Holding forth on the local team was a 19-year-old black youth who made several brilliant plays. Dykes said, “Geez, if that kid was white, I’d sign him right now.” In March of 1942, Dykes allowed the phenom and another black baseball player, Nate Moreland, to try out for the White Sox. He sent them away without an offer. Perhaps he allowed the tryouts only to deflect racial criticism, since no major league team had yet expressed any positive attitude toward integration. In any event, nothing came of it. How history might have changed if he had been able to offer a contract to that phenom, a lad named Jackie Robinson.

Curiously, many years later during spring training of 1961, when asked to comment on one of the better black major leaguers in the post-integration era, Dykes quipped, “Without Ernie Banks, the Cubs would finish in Albuquerque.”

Jimmy was a naturally feisty fellow, to be sure. As a player, he led the league three times in hit by pitches and finished in the top ten in this category 13 different seasons. Now as a manager, Dykes became a legendary umpire-baiter. Journalist Don McKean collected statistics that showed Dykes thrown out of 62 games in his managerial career and suspended or fined 37 times. His behavior became so critical that AL President Will Harridge suspended him July 6, 1941, announcing that the suspension was “for his conduct and language to umpire Steve Basil in the game played in Chicago. He will remain suspended until he can satisfy the American League office that in the future he will fall in line with the other seven managers of the league in conducting himself and his ball club on the field.” Team owner Grace Comiskey backed up her manager and the suspension was lifted the next week.

During the 1940s, Chicago became a team in the middle of that pack in league standings, between third and sixth place nearly every season. Team fortunes slipped during the war years, winning only 71 games in both 1944 and 1945. When the team stumbled out of the gate in 1946, losing 20 out of its first 30 games, Dykes was handed a pink slip, after nearly 12 seasons as manager with a composite record of 899-940. Ironically, Ted Lyons gave up his pitching career to take over as manager, though with less success.

Unable to catch on with another team, Jimmy was out of the major leagues in 1947 and was managing the Hollywood Stars of the Pacific Coast League for part of the season. Perhaps this time in Tinseltown inspired Dykes to make his film debut-playing himself in The Stratton Story opposite Jimmy Stewart. Though the movie won an Academy Award for Best Original Story, Dykes did not follow up his success with other films, instead focusing on the baseball diamond.

Jimmy returned to the major league dugout in 1949 back in his native Philadelphia on Connie Mack’s staff. Mack was nearing the end of his run in baseball and needed to groom a replacement, and Jimmy was his man. On May 25, 1950, the club announced that Connie’s son, Earle Mack, was reassigned from assistant manager to chief scout, and therefore no longer in line for succession. Former team hero Mickey Cochrane was brought in as general manager. On October 18, Mack made it official: he retired and Dykes was named manager. The team improved by 18 wins the next season, and actually compiled a winning record in 1952 (not to be matched for another 16 years by this wayward franchise). But a dismal year in 1953 led to another dismissal from the dugout.

This time, Dykes was unemployed for exactly one week. He resurfaced November 11 a few miles down the road as manager of the fledgling Baltimore Orioles. This city was returning to the majors after a 50-year absence, thanks to the acquisition and transfer of the St. Louis Browns franchise. However, the team succeeded only in avoiding 100 losses in their first season, and Jimmy’s contract was not renewed.

Dykes entered the National League for the first time in 1955 to coach for Birdie Tebbetts at Cincinnati. The Reds showed improvement in the next few seasons, but a slump in 1958 cost Tebbetts his job. Dykes took over August 14 with the club locked in seventh place at 52-61, and elicited marked improvement from the team as they went 24-17 under his tutelage, advancing from sixth to fourth place.

Surprisingly, the front office declined to renew his contract, so Jimmy signed on with Pittsburgh to coach the following season. His success in Cincinnati was not lost on major league general managers, however, and Dykes was considered the prime candidate for an early managerial change in 1959. It came in Detroit, which lost all but two of its first 17 games, and called in Dykes May 3 to reestablish some success. He did, guiding the Tigers to a 74-63 record the rest of the season and moving from eighth to fourth place. The following season did not start so well, however, as the team slid into sixth place, sitting at 44-52 as the dog days of summer were underway.

This set the stage for one of the strangest trades in major league history. August 3, 1960, saw Detroit and Cleveland trade-not players, not draft choices or future considerations-but rather, managers. Cleveland general manager Frank Lane conceived the idea and sold it to Detroit’s Bill DeWitt. The contract of Jimmy Dykes was transferred to Cleveland, while Joe Gordon was moved into Detroit. A truly bizarre swap, it was not a rousing success. Detroit stayed in sixth place and fired Gordon at season’s end. Dykes could not move the Indians out of fourth place that season, and slid to fifth the following year. That sealed his fate and closed his career as a major league manager.

In 21 seasons comprising nearly 3,000 games, he guided his teams to 1,406 victories. Yet Dykes never won a pennant, never finishing higher than third place, a pattern rivaled only by Gene Mauch. Dykes managed five different teams in the American League, a record matched only by Billy Martin. His total of six major league teams managed is the most of any 20th-century manager (Frank Bancroft managed most of his seven teams in the 19th century).

In contrast to his umpire baiting, Dykes was not the type to chew out his players in public; he called private meetings to do so. Pitcher Bobby Shantz, his ace hurler with the A’s, recalled. “He was the best manager I ever played for. He got more out of his players than any manager I had, including Casey Stengel.” (McKean)

After ending his managerial career, Dykes spent three more seasons coaching in major league dugouts – Milwaukee in 1962, and Kansas City in 1963 and ’64. He then retired to his native Philadelphia as radio commentator of the Phillies. The author grew up listening to Phillies radio broadcasts and remembers Dykes as host of a postgame broadcast and regular guest on longtime Phillies broadcaster Andy Musser’s nightly call-in show talking about the Phillies play and contemporary major league baseball. Dykes took up golf at the Bala Cynwyd Golf Club in the suburbs of Philadelphia, though in his later years he gave up the grand old game and focused on playing gin rummy in the clubhouse, no doubt enjoying his trademark cigar while playing.

Dykes passed away of an undisclosed illness many years into retirement, on June 15, 1976, at Hahnemann Hospital in his beloved city. He was buried in St. Denis Cemetery in suburban Havertown, Pennsylvania. Jimmy’s first wife, Mary, passed away in 1959, but his second wife, Mildred Boyle, survived him. Sons James Jr. and Charles, born a year apart, ironically died a year apart in 1964 and ’65. However, his daughter, Mrs. John T. Finnegan, and sister, Alice Ameson, were still alive. Dykes was proud to have 16 grandchildren and nine great-grandchildren.

Dykes said in reflecting on his career as a skipper, “The manager’s toughest job is not calling the right play with the bases full and the score tied in an extra inning game. It’s telling a ballplayer that he’s through, done, finished.” Jimmy played in many games where he executed the right play, but also gained a reputation for getting the most out of his players. His presence touched many lives over nearly five decades and left a lasting legacy for others to emulate.

Sources

McKean, Don. “Dykes dies; A’s player, manager,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, June 16 1976, pages D-1 and D-5. McKean was a sports reporter, not an obituary writer, and wrote an eloquent piece highlighting Dykes’ career. Additionally, The New York Times, June 16, 1976, provided details of Dykes’ family.

Thorn, John, and Pete Palmer, Total Baseball, Warner Books, New York City, 1991. This is the baseball researcher’s bible and provides many useful statistics on Dykes as a major league player and manager.

Many Internet sites were also consulted. www.blueridgeleague.org/history_1917.htm discussed his days playing in Gettysburg. http://www.baseballindex.org addressed Dykes’ ability to be hit by pitches. discussed his 1941 suspension. Other sources that supplied quotations and anecdotes were:

Bioproj.sabr.org

www.giga-usa.com/gigaweb1/quotes2/quautdykesjimmyx001.htm

http://www.znetsports.com/mlb/mlb_quotes2_index.asp

www.ballparks.com/baseball/general/chatter/20010905.html (written by C. Philip Francis)

http://espn.go.com/sportscentury/features/00107091.html

http://quote.webcircle.com/cgi-bin/search.cgi?idPlayer=223

Full Name

James Joseph Dykes

Born

November 10, 1896 at Philadelphia, PA (USA)

Died

June 15, 1976 at Philadelphia, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.