August 4, 1910: Jack Coombs, Ed Walsh hook up in scoreless, 16-inning pitchers’ duel for the ages

It was an epic pitchers’ duel between the Philadelphia Athletics’ Jack Coombs and the Chicago White Sox’ Big Ed Walsh. “Sixteen scoreless innings of desperate pastiming with dusk the winner,”1 declared the Philadelphia Inquirer, while the Chicago Tribune opined, “[N]either side had the shadow of a right to win against such pitching.”2 Windy City sportswriter Fred J. Hewitt of the Inter Ocean wrote that “One got powerfully tired of eyeing those ciphers as they crept along on two continuously growing lines on the top of the scoreboard.”3

It was an epic pitchers’ duel between the Philadelphia Athletics’ Jack Coombs and the Chicago White Sox’ Big Ed Walsh. “Sixteen scoreless innings of desperate pastiming with dusk the winner,”1 declared the Philadelphia Inquirer, while the Chicago Tribune opined, “[N]either side had the shadow of a right to win against such pitching.”2 Windy City sportswriter Fred J. Hewitt of the Inter Ocean wrote that “One got powerfully tired of eyeing those ciphers as they crept along on two continuously growing lines on the top of the scoreboard.”3

Skipper Hugh Duffy’s Pale Hose squad was reeling as they prepared to conclude a four-game series with the AL-leading A’s as part of a five-team, 20-game homestand in White Sox Park, inaugurated just five weeks earlier, on July 1, and immediately advertised as the Base Ball Palace of the World. The White Sox had lost 23 of their last 29 games to fall to 36-57 and land in seventh place, 26 games off the A’s pace. Connie Mack, the owner-skipper of the A’s, was none too pleased about his club’s recent performance despite its first-place position (62-31) and 5½-game lead over the Boston Red Sox. The A’s had won only seven of their last 15 games, with one tie.

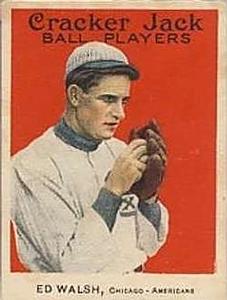

Toeing the rubber for the White Sox was Ed Walsh, a 29-year-old right-hander and one of the most durable and best hurlers in baseball. Two years earlier, he had won a big-league-most 40 games, entered the season with a 110-63 slate, and had thrice paced the circuit in shutouts, which accounted for his minuscule 1.68 career ERA. Big Ed’s 11-15 slate thus far in ’10 reflected the sorry state of his team, not his pitching, as he went on to lead the majors with a 1.27 ERA despite 20 losses. Mack countered with Coombs, a 27-year-old righty who was emerging as the most dominant pitcher in baseball, at least for one season, and was making his 12th start in the last 35 days. Colby Jack (so named for his pitching success at Colby College in Maine) was one of the reasons the Mackmen were in first place. On the heels of a mediocre 35-35 slate in his first four seasons, Coombs boasted a 17-6 record and had registered shutouts in four of his last seven starts.

On a warm Thursday afternoon, 5,100 spectators settled in White Sox Park, located at the intersection of 35th Street and Shields Avenue on Chicago’s South Side, for a 3:30 start time. [The ballpark was renamed Comiskey Park, after the owner Charles Comiskey, for the start of the 1913 season.] Their first chance to cheer probably occurred when Patsy Dougherty led off the second with a double. It was the White Sox’ first hit — and last until the 12th inning. Possessing what Hewitt described as a “deceiving selection of baseball curveatures,” Coombs whiffed two of the next three batters and had six punchouts through three innings.4

The White Sox’ best scoring chance for the game came when Coombs walked Freddy Parent and hit Paul Meloan to begin the fourth. After fanning Dougherty, Coombs uncorked a wild pitch, enabling both runners to advance. Lee Tannehill hit a hard grounder to second baseman Eddie Collins, who threw home to catcher Paddy Livingston. In a costly baserunning blunder, the runners had already committed; as Parent raced back to third, he met Meloan. Livingston, meanwhile, had thrown to Home Run Baker, who tagged both runners; Meloan was ruled out. The inning ended a few moments later when Tannehill was thrown out at second on a delayed double steal.

Through nine innings, Coombs had fanned 12, marking the first time in his career he had reached double-digit strikeouts in a game, and he was far from finished.

While Coombs mowed down the White Sox, Walsh’s spitter was “working to perfection,” gushed Hewitt, mesmerizing the Mackmen.5 Two defensive miscues put pressure on Big Ed in the seventh. After second baseman Charlie French juggled Eddie Collins’s grounder, Walsh threw Baker’s bunt attempt into center field. Harry Davis moved both runners a station on a sacrifice bunt. Danny Murphy followed with a single to right field which “[p]robably would have settled it if Ed Collins had known it was going to fall safe,” reported the Tribune.6 Meloan fielded the ball on one hop and his throw held Collins at third. Walsh, keeping “infernally busy” (according to the Inter Ocean), retired to the next two batters.7

The crowd got a laugh in the 11th when a dog jumped from the grandstand and delayed the game for five minutes until “heroic work by Donahue finally resulted in his banishment,” reported the Tribune.8 For the second time in three innings, the A’s Home Run Baker reached second base, where he was stranded.

After holding the White Sox hitless for 10⅓ innings, Coombs yielded a one-out single to Meloan in the 12th. The robust 6-foot, 190-pound hurler “seemed to be groggy,” opined the Tribune, “and was walking around out there as if he knew not what was expected of him.”9 After Dougherty’s single, Baker scooped up Tannehill’s grounder at third to initiate an inning-ending twin killing.

While the Tribune lamented that the “pressbox supply of cigarettes ran out” in the 13th inning, both hurlers traded punches like heavyweight boxers Jack Johnson and James L. Jeffries in their championship bout a month earlier in Reno, Nevada.10 As overpowering as Coombs was, the A’s defensive wizardry was the unsung key of the game. In the 13th, Eddie Collins saved his hurler when he snared Billy Sullivan’s sharp liner and doubled Billy Purtell off second to end the frame. Collins had a repeat performance two innings later with Meloan and Tannehill on base via Coombs’ fifth and sixth free passes of the game. Collins caught Purtell’s liner and doubled Tannehill off first to end the inning.

Remarkably durable, Walsh was back on the mound to start the 16th. It was the seventh time in 25 starts thus far in ’10 that Big Ed had hurled at least 10 innings, including two 15-inning and one 14-inning victories. With dusk arriving, Walsh led off the fateful last frame with his third and final walk, to Rube Oldring. Collins followed with what seemed to be a routine double-play grounder, but Walsh’s throw sailed into second base, putting runners on the corners with no outs. The future Hall of Famer extracted himself by inducing two infield foul outs and a grounder.

As Jimmy Dygert warmed up in the bullpen, Coombs was back on the mound in the 16th, just the fourth time in his career that he had pitched at least 10 innings in a game. It was “so dark that hitting was more or less a matter of guess work,” opined the Tribune, as home-plate umpire Bill Dinneen announced that the game would be over after this frame no matter what. Catching a second wind, Coombs unleashed a torrent of fastballs, which the Tribune claimed looked like “polka dots in the [catcher’s] glove”11 and, according to the Inquirer, “fast breaking curves, balls which whistled through the gloaming at tantalizing speed.”12 In overpowering fashion, Coombs whiffed Charlie Mullen, Sullivan, and Walsh in succession to end the game in a 0-0 tie after 3 hours and 28 minutes to the disbelief of the few remaining spectators.

In their remarkable pitchers’ duel, Coombs and Walsh pitched arguably the best games of their careers, and certainly the longest. Walsh faced 60 batters, surrendered just six hits, and fanned 10. In his three-hitter while facing 54 batters, Coombs set a major-league record with 18 strikeouts, including French and Walsh four times each.

Neither pitcher slowed down after their epic match. Three days later, Walsh tossed a two-hit shutout against the Washington Senators and fanned 10. On August 11, he blanked the Boston Red Sox on three hits and tied his career high with 15 punchouts. He finished the season with a misleading 18-20 record and led the AL in losses.

Combs was in one of the best stretches in baseball history. Three days later he blanked the St. Louis Browns on five hits at Sportsman’s Park. From July 1 through the end of the season, he went 24-5, including 10 straight wins, completed 25 of 27 starts, and tossed 12 shutouts, including four straight in September as part of a then-record 53 consecutive scoreless innings. He capped off his 31-9 season by tossing three consecutive complete-game victories against the Chicago Cubs in the World Series, giving Connie Mack his first of five championships.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also accessed Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, SABR.org, and The Sporting News archive via Paper of Record.

Notes

1 “Coombs Hurls Wonderful Ball Against White Sox,” Philadelphia Inquirer, August 5, 1910: 10.

2 “Sox Tie Macks in 16 Innings, 0 to 0,” Chicago Tribune, August 5, 1910: 8.

3 Fred J. Hewitt, “Sox and Athletics Go Sixteen Innings and Nary a Score,” (Chicago) Inter Ocean, August 5, 1910: 5.

4 Hewitt.

5 Ibid.

6 “Sox Tie Macks in 16 Innings, 0 to 0.”

7 Hewitt.

8 “Sox Tie Macks in 16 Innings, 0 to 0.” Hewitt in the Inter Ocean reported that the incident happened in the ninth inning.

9 “Sox Tie Macks in 16 Innings, 0 to 0.”

10 Ibid.

11 Ibid.

12 “Coombs Hurls Wonderful Ball Against White Sox.”

Additional Stats

Philadelphia Athletics 0

Chicago White Sox 0

16 innings

White Sox Park

Chicago, IL

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.