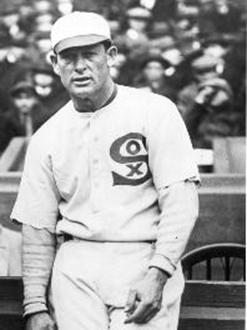

Big Ed Walsh

From 1907 to 1912, “Big Ed” Walsh tested the limits of a pitcher’s endurance like no pitcher has since. During that stretch the spitballing right-hander led the American League in innings pitched four times, often by staggeringly large margins. He hurled a total of 2,248 innings, 300 more than any other pitcher in baseball. He started 18 more games than any other pitcher, and led the American League during that stretch in games finished and saves, though the latter statistic would not be tracked for another 60 years. His finest season came in 1908, when Walsh became the last pitcher in baseball history to win 40 games, and hurled an incredible 464 innings, 73⅓ more than any other pitcher in baseball.

From 1907 to 1912, “Big Ed” Walsh tested the limits of a pitcher’s endurance like no pitcher has since. During that stretch the spitballing right-hander led the American League in innings pitched four times, often by staggeringly large margins. He hurled a total of 2,248 innings, 300 more than any other pitcher in baseball. He started 18 more games than any other pitcher, and led the American League during that stretch in games finished and saves, though the latter statistic would not be tracked for another 60 years. His finest season came in 1908, when Walsh became the last pitcher in baseball history to win 40 games, and hurled an incredible 464 innings, 73⅓ more than any other pitcher in baseball.

A fierce competitor, Walsh wanted the heavy workload the White Sox hoisted upon him. He also fielded his position with as much agility as any pitcher in the history of the game. During his six-year stretch of historic greatness, Walsh accumulated 963 assists, an amazing 344 more than any other pitcher in baseball. He fielded bunts like a territorial animal. Once, when a new third baseman came in for a bunt with a runner on second, Walsh got to the ball but couldn’t make a play to third because it was uncovered. Walsh then reputedly turned to the third baseman and said, “If you do that again, I’ll kill you. On bunts on that side of the field, you stay where you belong.”1 Though he finished his career with the lowest ERA (1.82) in baseball history, Walsh’s arm couldn’t withstand the overuse, and by 1913 the “Iron Man” pitcher was a shadow of his former self. Despite winning an impressive 182 games before his 32nd birthday, Walsh finished his career short of 200 wins.

Edward Augustine Walsh was born on May 19, 1882 (although census records place his year of birth variously as 1880 or 1881) in Plains, Pennsylvania, one of 13 children — 10 boys and three girls — of Michael and Jane Walsh. Edward’s father was a native of Ireland who immigrated to the United States in 1866, where he found work as a shoemaker and married Jane, a heavy-set Welsh immigrant who had crossed the Atlantic in 1854. Edward’s mother was active in the local Catholic church choir, and often sang old Irish folk songs to her children. Ed attended parochial school until he reached the age of 12, when he began work as a slate-picker in the Plains mines for the Lackawanna Coal Company, earning 75 cents a day. For an additional $1.25, Ed also drove mule-drawn coal carts in the mines.

At age 18 he enrolled at Fordham University but left after only two days because he hated the wild students and grown men who were his roommates. Returning to Pennsylvania, Walsh began his baseball career as a pitcher for the Miner-Hillard Milling Company in Miners Mills, Pennsylvania, in 1901. In July 1902 Walsh signed his first professional contract, agreeing to terms with the Meriden Silverites of the Connecticut League for $150 per month. Walsh posted an impressive 16-5 record in Meriden before Wilkes-Barre of the Pennsylvania State League picked him near the end of the season. After winning only one of four decisions for Wilkes-Barre, Walsh was sold back to Meriden, where he spent the first part of the 1903 season before his skills caught the attention of Newark of the Eastern League. He finished out the 1903 campaign with Newark, notching a 9-5 record. After the season the Chicago White Sox purchased his contract for a mere $750.

Throughout his minor-league career, the 6-feet-1 193-pound Walsh — whose unusual height for his time earned him the moniker “Big Ed” — relied exclusively on a fastball and curve. During 1904 spring training with the White Sox in Marlin Springs, Texas, Walsh roomed with spitballer Elmer Stricklett, the same pitcher who had inspired Jack Chesbro to start experimenting with the pitch the year before. Stricklett taught Walsh the spitter, but the big right-hander did not start using the pitch for two years. As a spot starter and reliever for the White Sox in 1904 and 1905, Walsh went 14-6 with a solid 2.37 ERA. It was not until the 1906 campaign, when the White Sox captured their second American League pennant in six major-league seasons, that Walsh began to use the spitter on a regular basis. Although pitching with a weakened right arm for part of the season, Walsh put up his best regular-season numbers to date, posting a 17-13 record with a 1.88 ERA, seventh best in the league, and a league-leading 10 shutouts. But he saved his best work for the World Series, when he beat the cross-town Chicago Cubs twice in two starts, allowing only one earned run (and five unearned) in 15 innings of work, and striking out 17 batters, including a then-Series record 12 in a Game Three shutout.

On the heels of his World Series triumph, Walsh put together his first 20-win season in 1907. In a reflection of his competitive nature, he also began to change his approach on the mound. “Early in my career I eased up in the first few innings to save myself, but I found I couldn’t get back into stride after once letting up,” he later explained. “After that, I threw hard all the time. I threw my best to every hitter I faced and I found I had the strength to go all the way.”2

In 1908 Walsh put together his masterpiece, compiling 40 wins against just 15 losses, a 1.42 ERA, including a league record-breaking 11 shutouts, and 464 innings pitched. Pushing himself to the limit, during one nine-day stretch Walsh pitched five times, including a four-hitter on October 2 that he lost to Addie Joss, who threw a perfect game. Walsh’s pitching kept the White Sox in the American League’s thrilling four-way pennant race until the last day of the season, and the club finished in third place, 1½ games behind the front-running Detroit Tigers. For the season, Walsh struck out 269 batters, a career best, and walked only 56 men, giving him the fourth lowest walk rate in the majors that year.

Not surprisingly, at the time Walsh’s spitball was considered the most effective pitch in baseball. Walsh disguised the pitch by going to his mouth before every delivery, regardless of what he was going to throw. When he did throw the spitter, according to Alfred Spink he moistened a spot on the ball between the seams an inch square. “His thumb he clinches tightly lengthwise on the opposite seam, and swinging his arm straight overhead with terrific force, he drives the ball straight at the plate,” Spink wrote. “At times it will dart two feet down and out, depending on the way his arm is swung.”3

In a 1913 article for Baseball Magazine, Walter Johnson called Walsh’s delivery “about the most tantalizing in baseball” for the way it arrived at the plate “with such terrific speed, and unerringly dives just as if it knew what it was about and tried to dodge the hitter’s bat…”4 For all practical purposes, the pitch was the Deadball Era equivalent of the split-fingered fastball, and absolutely devastating to batters accustomed to seeing mostly fastballs and curves. “I think that ball disintegrated on the way to the plate and the catcher put it back together again,” Sam Crawford later joked. “I swear, when it went past the plate it was just the spit went by.”5

When batters did reach base, Walsh often picked them off with the game’s most deceptive move to first base. In a motion that would probably be ruled a balk today, Walsh lifted his shoulder slightly, as if beginning his motion to throw home, before swinging around and firing the ball to first. Clyde Milan, one of the era’s best base stealers, declared the move “at least a half balk” but Walsh got away with it anyway.6

In 1909, Walsh’s numbers dipped as he recovered from the heavy workload he had sustained the year before. Starting in only 28 games, he finished the year with a 15-11 mark in 230⅓ innings, less than half his 1908 total. Though his 1.41 ERA was nearly identical to his 1908 mark, Walsh’s strikeout rate fell slightly while his walk rate nearly doubled. The cause of this sudden bout of “wildness” was that he was tipping his pitches. Specifically, the Cleveland Naps believed they had deciphered when he was going to throw the spitter, by noticing that he had a habit of ticking the bill of his cap prior to unleashing a wet one. Word spread quickly around the league, and hitters started to lay off the spitter, which usually dropped out of the strike zone. When Walsh learned what was happening, he changed his style. In 1910, Walsh finished with 18 wins against 20 losses, but the losing record was deceptive: Walsh’s 1.27 ERA was the best of his career and also good enough to lead the league. In 1911 Walsh’s ERA rose nearly a full run to 2.22, but he received better run support and won 27 games against 18 defeats in 368⅔ innings pitched. In 1912 he again won 27 games, tossed six shutouts, collected a league-record 10 saves, and finished the year with a 2.15 ERA in 393 innings of work.

The first sign that his powerful right arm was about to give up on him occurred in the Chicago city series at the end of the 1912 season. In one outing against the Cubs Walsh took a line drive off his jaw. He went on pitching, but after the game his arm felt weak. Looking back, Walsh blamed himself for his sudden decline. “It was my fault I didn’t continue in the majors longer than I did,” Walsh said. “My arm was played out after the 1912 season — it needed a rest.”7 Instead, Walsh began the 1913 season still trying to fulfill the role as the staff’s workhorse. He started 14 games, going 8-3 with a 2.58 ERA, but often required long periods of rest between starts. After lasting just five innings against the Philadelphia Athletics on July 19, Walsh was shelved indefinitely, and left the team to have his arm examined by Bonesetter Reese in Youngstown, Ohio. Reese looked over Walsh and declared that he had a “misplaced tendon” in his right shoulder. According to the New York Times, Reese fixed the pitcher in three minutes and declared he would be better than ever the following season.8

It didn’t happen. Over the next three seasons Walsh pitched sparingly for the White Sox, starting only nine games from 1914 to 1916 and winning five. During that time he rejected a lucrative offer from the Federal League, and at one point contemplated becoming an outfielder. During the 1916 season Walsh appeared in only two games, pitching 3⅓ innings. His most notable achievement came in late July, when he rescued two girls from drowning in Lake Michigan.9 Let go by the White Sox at the end of the season, Walsh made a brief appearance with the Boston Braves in 1917, going 0-1 with a 3.50 ERA in 18 innings of work.

During World War I Walsh worked in a munitions factory. Thereafter he pitched briefly for Milwaukee of the American Association in 1919, Bridgeport (Connecticut) of the Eastern League in 1920, and finally with a semipro club in Oneonta, New York in 1921. He spent the first half of the 1922 season as an umpire for the American League. Walsh hated the job, mainly because he did not like calling strikes. “I remember when I wanted every pitch to be a strike,” he said.10 For the next several years he served as a coach for the White Sox, and after that was a battery coach at Notre Dame, where his son pitched. Ed Walsh, Jr. spent parts of four seasons in the major leagues, but his most notable achievement came in 1933, when as a pitcher for the Oakland Oaks of the Pacific Coast League he halted young Joe DiMaggio‘s 61-game hitting streak. Tragically, the younger Ed died suddenly of rheumatic fever in 1937. That same year, Ed’s other son, Bob, also a graduate of Notre Dame, gave up baseball when he was almost hit with a line drive while playing for the Richmond club in the Piedmont League.

The Great Depression hit Walsh hard: his $14,000 investment in a show place on Hanover Road in Meriden went belly-up and for six years he worked for the Works Progress Administration, conducting a baseball school through the agency’s recreational program. Toward the end of the decade Walsh became a chemical engineer and worked at a filtration plant for the Meriden municipal water department. When he wasn’t working, Walsh indulged his love for golf, and became the course professional in Meriden.

To the end of his life, Walsh pushed for the spitball to be legalized. He once said, “everything else favors the hitters. Ball parks are smaller and baseballs are livelier. They’ve practically got pitchers wearing straitjackets. Bah! They still allow the knuckleball and that is three times as hard to control.”11

Walsh was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame on July 21, 1947, and was the only one of that year’s fifteen inductees to attend the ceremony, but he and his wife Rosemary struggled to make ends meet. By the late 1950s Walsh had contracted cancer. The disease impacted him greatly, as his weight dropped from 200 pounds to less than 100. To help pay his medical bills, the White Sox held an Ed Walsh Day at Comiskey Park in 1958, raising nearly $5,000 for his care. Ed Walsh died on May 26, 1959, two weeks after his 77th birthday (or 78th or 79th, depending on the source). He was buried in Forest Lawn Memorial Gardens in his adopted hometown of Pompano Beach, Florida.

An updated version of this biography is included in “20-Game Losers” (SABR, 2017), edited by Bill Nowlin and Emmet R. Nowlin. It was originally published in SABR’s “Deadball Stars of the American League” (Potomac Books, 2006), edited by David Jones.

Sources

Ed Walsh player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

Broeg, Bob. “A St. Pat’s Salute to Ed Walsh,” The Sporting News, March 24, 1979: 40.

Holtzman, Jerry. “Big Ed Walsh, 77, Former White Sox Star, Gets day to Remember at Comiskey Park,” The Sporting News, July 2, 1958: 7.

Keener, Sid C. “Walsh Weary,” Sporting Life, July 12, 1913.

Meany, Tom. “Bid Ed Walsh’s Fabulous Week,” Baseball Digest, August 1959: 59-60.

Parker, Dan. “Big Ed Walsh Still Pitches a Fast One,” Daily Mirror, January 30, 1946.

Peck, Howard H. “How ‘Big Ed’ Got the Spitball,” The Courant Magazine, December 16, 1956: 4.

Smith, Red. “Views of Sport: Ed’s One Bad Year,” New York Herald Tribune, January 12, 1947.

“Big Ed Gave Game Many Transfusion: Walsh Rebuilding Huge frame to accept Baseball Honors,” Miami Herald, June 19, 1958: 4-D.

Notes

1 Undocumented quotation.

2 Ed Walsh, “Pitching only 30 Pct. Now — Walsh,” The Sporting News, January 9, 1957: 13.

3 Alfred Henry Spink, The National Game (St. Louis; National Game Publishing, 1910), 162.

4 Lawrence S. Ritter, The Glory of Their Times (New York: Harper Perennial, 2010), 56.

5 Ibid.

6 F.C. Lane, “Milan the Marvel,” Baseball, May 1914: 101.

7 Undocumented quotation.

8 “Tendon in Walsh’s Arm Adjusted,” New York Times, August 20, 1913: 7.

9 “Ed Walsh Saves Two Girls,” Chicago Tribune, July 28, 1916: 3.

10 “Big Ed Walsh, Former Oneonta Baseball Manager, Dies at 78,” Oneonta Star, May 27, 1959: 12.

11 “Walsh, Winner of 40 Games in One Season for White Sox, Dies at 78,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, May 27, 1959.

Full Name

Edward Augustine Walsh

Born

May 14, 1881 at Plains, PA (USA)

Died

May 26, 1959 at Pompano Beach, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.