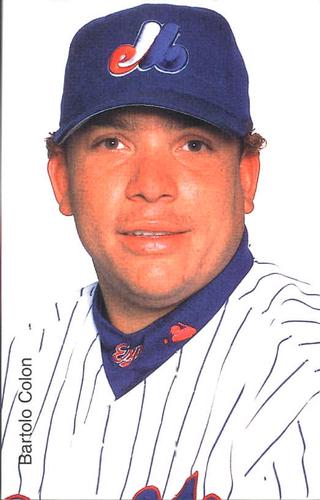

August 9, 2002: Bartolo Colón records his first multi-hit game

Montreal Expos general manager Omar Minaya had shocked the baseball world. Just over a month before the 2002 trade deadline, he acquired the most coveted player available, Bartolo Colón, in a blockbuster deal with the Cleveland Indians. The Expos paid dearly to obtain one of the best pitchers in the game. In what turned out to be one of the most lopsided trades in baseball history, Montreal sent Cliff Lee, Brandon Phillips, Grady Sizemore, and Lee Stevens to Cleveland in return for the 29-year-old Colón and minor-league pitcher Tim Drew.1

Montreal Expos general manager Omar Minaya had shocked the baseball world. Just over a month before the 2002 trade deadline, he acquired the most coveted player available, Bartolo Colón, in a blockbuster deal with the Cleveland Indians. The Expos paid dearly to obtain one of the best pitchers in the game. In what turned out to be one of the most lopsided trades in baseball history, Montreal sent Cliff Lee, Brandon Phillips, Grady Sizemore, and Lee Stevens to Cleveland in return for the 29-year-old Colón and minor-league pitcher Tim Drew.1

Minaya had nothing to lose in the one-sided deal. The beleaguered Expos had narrowly avoided contraction during the previous offseason after being taken over by Major League Baseball. Expos fans, tired of the regular fire sales that sent their stars to big-market clubs in return for cheaper talent, had largely thrown in the towel. In 2001, just under 8,000 fans per game made the trek to gloomy Olympic Stadium to witness the team’s fourth consecutive season of at least 94 losses. With the threat of relocation or contraction still looming, 2002 could have been their final season in Montreal. Minaya’s trade for Colón was a Hail Mary pass. “We were trying to save the team by trying to contend,” he said years later. “But we felt if we got into the playoffs, the town would have supported us, and the private sector would offer more support. We saw it in Seattle,” when the Mariners gained momentum toward a new ballpark after their playoff run in 1995.2

On the day the Colón deal was made, the young Expos were in second place, 6½ games behind the Atlanta Braves in the NL East. But the trade failed to have the desired effect, and the team came into its August 9 game against the Brewers with its playoff hopes slipping away. Montreal, with a 57-57 record, had fallen a whopping 18 games behind the surging Braves. Even though they were only 6½ games behind the Dodgers in the wild-card race, they had the unenviable task of trying to overtake five teams to claim the wild-card spot.

The Brewers, who hadn’t made the playoffs since 1982, were stumbling their way through their 10th consecutive losing season. They fired their manager, Davey Lopes, after a 3-12 start, and his replacement, Jerry Royster, fared no better. Milwaukee entered the game with the worst record in the National League at 40-74.3

Colón took to the hill for his eighth start in an Expos uniform. He had continued to pitch well after the trade, and his combined record with Cleveland and Montreal stood at 14-5 with a tidy 2.67 ERA. The Brewers countered with 23-year-old right-hander Rubén Quevedo, who had been struggling mightily of late. In his last four starts, Quevedo had posted a 10.29 ERA and watched his season record fall to 6-9.

The Expos got on the scoreboard early: Brad Wilkerson led off the game with a walk, and utilityman José Macías, making a rare start at shortstop, followed with a two-run homer. It was Quevedo’s league-leading 26th home run allowed.

Colón had spent his entire career in the American League before coming to Montreal, so he hadn’t had many opportunities to swing the bat. When he stepped to the plate in the top of the second inning, his career batting line was 6-for-45 with no walks or extra-base hits, and he had struck out in over 52 percent of his plate appearances. Surprisingly, Colón crushed a Quevedo offering past third baseman Mark Loretta, who was playing even with the bag, into left field for a base hit. Colón, perhaps as shocked as anyone, smiled broadly and let out a chuckle after reaching first base. He was stranded on the basepaths, however; a walk to Wilkerson was the only other offense the Expos could muster in the inning.

After an RBI groundout by Michael Barrett extended the Montreal lead to 3-0, Colón came to the plate with runners on second and third and two out in the third inning. The Expos hurler defied the odds once more by smacking a hard line-drive base hit up the middle to knock in two more runs and give him the first multi-hit game of his career. Wilkerson followed with a double to move the slow-footed Colón to third, and then José Macías’s two-bagger scored both runners to blow the game open and put the Expos up 7-0. All seven runs against Quevedo were earned.

Colon wasn’t his usual dominant self on the mound, although he limited the damage by escaping a pair of bases-loaded jams with a total of only one run allowed. Altogether he surrendered four earned runs in seven innings of work, with the damage coming on a two-run homer by Matt Stairs and RBI groundouts by Israel Alcántara and Richie Sexson. Montreal added an eighth run when Macías picked up his career-high fifth RBI of the game on a sacrifice fly.

The Expos held an 8-4 lead as the teams headed into the ninth inning. Guerrero led off the final frame by launching a solo home run, the 200th of his career. “It’s a good thing the fence wasn’t any higher,” quipped Montreal manager Frank Robinson. “He would have put a hole in it.”4 Montreal tacked on two more runs on a wild pitch from Mike DeJean that scored a runner from third and an RBI single by Wilkerson. Reliever T.J. Tucker easily retired the Brewers in the bottom of the ninth to nail down the 11-4 victory.

Minaya’s hopes for a storybook finish to the Expos’ season didn’t pan out. Despite winning 12 of their last 15 games in September, Montreal finished in second place with an 83-79 record, leaving them a distant 12½ games out of the wild-card spot.

Instability continued to plague the Expos in the offseason. Minaya had acquired Colón under the premise that he would be under team control through the 2003 season, but MLB reversed course in the fall of 2002 and ordered Minaya to slash the team’s payroll. Colón, with a salary of $8.5 million, was the team’s highest-paid player, and so he had to go. Everyone in baseball knew that the Expos had to dump him, so it was next to impossible to get fair market value for one of the game’s best hurlers. On January 15, 2003, Montreal unloaded Colón and minor-leaguer Jorge Nunez to the White Sox for the oft-injured Orlando “El Duque” Hernández, Rocky Biddle, Jeff Liefer, and (not surprisingly) cash.5 The Expos survived two more seasons in Montreal before they were relocated to Washington for the 2005 season.

Colón remained an elite pitcher upon his return to the American League, and he won the Cy Young Award in 2005 by a wide margin. He battled elbow issues during the next four years, which forced him to sit out the entire 2010 season, although he made a successful comeback in 2011 and went on to record the best season of his career as a 40-year-old with the 2013 Oakland A’s. He returned to the National League in 2014 with the Mets. During his three seasons in Queens, Colón became a folk hero, largely due to his adventures at the plate. By 2016, the 5-foot-11, 285-pounder was the oldest player in baseball, which only added to his mystique.

Colón, affectionately nicknamed “Big Sexy” by his Mets teammates, worked diligently to improve his hitting while in New York. His efforts were rewarded. On May 7, 2016, only 17 days before his 43rd birthday, he hit a home run off James Shields to become the oldest player in history to hit his first major-league home run. Just over three months later, Colón drew his first-ever walk in his 282nd career plate appearance, setting the big-league record for the longest streak without a walk at the beginning of a career. Finally, on August 15, 2016, Colón recorded the second multi-hit game of his career, more than 14 years after accomplishing the feat with the Expos.

One by one, the players who had at one time worn a Montreal Expos jersey retired. Even though their team hadn’t existed in years, certain Expos fans took comfort in the fact that a few of their former players were still active in the big leagues.6 When spring training opened in 2016, only two players remained: Colón and 35-year-old Maicer Izturis.7 And then, on March 4, 2016, Izturis announced his retirement from baseball, making Colón the last Expo standing.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org.

baseball-reference.com/boxes/MIL/MIL200208090.shtml.

retrosheet.org/boxesetc/2002/B08090MIL2002.htm.

Notes

1 Cliff Lee, Brandon Phillips, and Grady Sizemore went on to combine for a total of 10 All-Star appearances. They also won a Cy Young Award, four Gold Gloves, and two Silver Slugger Awards. Bartolo Colón made only 17 starts in an Expos uniform, and Tim Drew posted a 7.02 ERA in 35 career big-league appearances.

2 Jonah Keri, Up, Up & Away: The Kid, The Hawk, Rock, Vladi, Pedro, Le Grand Orange, Youppi!, The Crazy Business of Baseball, & the Ill-fated but Unforgettable Montreal Expos (Toronto: Random House Canada, 2014), 371.

3 The Milwaukee Brewers finished the 2002 season with an abysmal 56-106 record. Their .346 winning percentage is still the worst in franchise history (as of the end of the 2018 season). Even the 1969 Seattle Pilots won eight more games than the 2002 Brewers.

4 Associated Press, “Expos Still in There Fighting,” Wisconsin Rapids Daily Tribune, August 10, 2002: 11.

5 Orlando Hernández never threw a single pitch for the Expos in a regular season game. The 37-year-old was diagnosed with a torn rotator cuff during spring training in 2003, and he missed the entire season. Hernández became a free agent after the 2003 season and re-signed with the New York Yankees.

6 In 2010 one fan even started a blog dedicated to following the former Expos who were still active in the major leagues. The blog’s archives are still available at lastexpostanding.wordpress.com. (Accessed May 23, 2019)

7 Maicer Izturis made his major-league debut with the Expos on August 27, 2004, roughly five weeks before the end of their final season in Montreal.

Additional Stats

Montreal Expos 11

Milwaukee Brewers 4

Miller Park

Milwaukee, WI

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.