July 1, 1910: ‘Baseball Palace of the World’ opens with White Sox’s first game at Comiskey Park

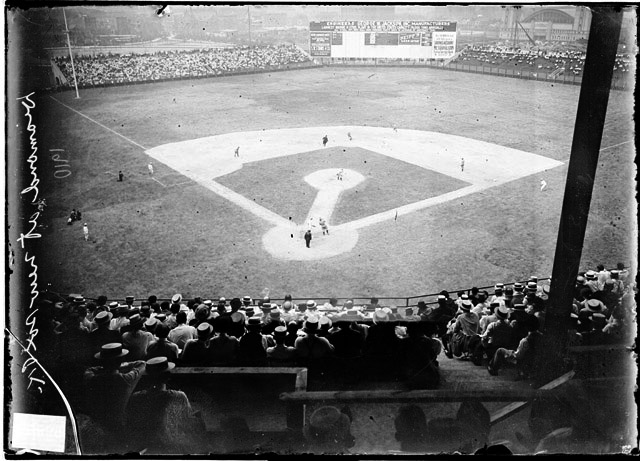

On a sweltering summer afternoon on July 1, 1910, the ballpark that would one day be known as Comiskey Park hosted its first official game. At the time, the ballpark was known as White Sox Park. The Chicago White Sox would play 6,247 major-league games there before it closed on September 30, 1990.

Charles Comiskey, the White Sox owner, was hailed by I.E. Sanborn of the Chicago Tribune as the “noblest Roman of them all” and as the architect of the “greatest baseball plant in the world” which “combines every perfection of its predecessors in other cities and in which no expense has been spared to remove all imperfections of other plants of similar nature.”1 Officially, 24,900 paid spectators came to see this opening extravaganza, but two Chicago newspapers agreed that the number was in reality closer to 30,000 than 25,000, with the entire musical accompaniment. And it probably seemed as if the entire city had been there that day, yet the mammoth ballpark still appeared to have room for more as the “great stands smilingly held out their bunting clad arms and gathered them all into their capricious laps without crowding anywhere,” wrote Sanborn.2

The stadium was a remarkable feat, considering that it was assembled in just four months, minus the five weeks of stalled labor because of a steelworkers strike. The huge electrical scoreboard was still being completed just days before the game, and painters were still busy right up to game time. “Electricians have already have strung their wires from the press stand to the working devices on the board,” the Tribune reported.3 That new press box was located in the front of the second deck behind home plate. Home plate was new, but the flagpole from South Side Park was unearthed and placed in the northwest corner of the field.4

The grandstand and pavilion entrances were at 35th and Shields Avenue, where you could pass through one of the 14 turnstiles on your way to your 50-cent, 75-cent, or $1 seat. The 25-cent seats had an entrance on 34th and Shields, and the 50-cent seats in the third- and first-base pavilions had separate entrances. Reserved seating in the upper deck and box seats were 75 cents.5 If you were one of the few fans with an automobile, you entered at 33rd and Shields. At 1 P.M. on July 1, 1910, the gates of the sparkling new ballpark were opened for the first time, and more than 1,000 eager fans rushed in to be the first to experience the new structure. As they dashed in, they passed departing construction workers who had been working right up to the last minute.6

The inaugural crowd was treated to the playing of “My Country ’Tis of Thee,” “Has Anybody Here Seen Kelly?” and “Cheer! Cheer! The Gang’s All Here” by five different bands. The Chicago Automobile Club led a parade of streamer- and banner-bedecked automobiles that made their way to the park.7 A floral display of bats and a ball were placed on the field with white socks hanging beneath.

At 3 P.M. Comiskey marched to home plate to thunderous applause and Mayor Fred A. Busse presented him with a purple banner that read, “The City of Chicago Congratulates Comiskey.” American League President Ban Johnson and August “Garry” Herrmann, owner of the Cincinnati Reds and chairman of the National Commission, were also present at home plate. The American flag was raised, and the band played “The Star Spangled Banner.” “Out across the mighty field in the great grand stand and in the pavilions and in the sun bleachers the 30,000 devotees of the national sport roared and shouted and screamed and sang in unison with that piece the band was playing,” wrote Harry Daniel of Chicago’s Inter-Ocean.8

The temperature at game time was officially 92 degrees, but the unofficial thermometers on the street hit 96. Ten people died of heat-related causes in Chicago that day.9

The White Sox emerged in new uniforms of dazzling white and blue trim. Chicago had on the mound Big Ed Walsh, one of the Deadball Era’s greatest pitchers and a future Hall of Famer. (His 1.82 career ERA still ranks number one all-time.10) Going into the 1910 season, Walsh was 110-63 with a 1.68 ERA, and in 1908 he led the league in many pitching categories. Billy Sullivan made his first start of the season as catcher. The veteran Sullivan had been recovering after stepping on a rusty nail in spring training and nearly losing his leg when a quack physician recommended that he receive a nearly lethal dose of turpentine. The “grand little backstop” received tremendous ovations throughout the day.11

The Browns sent veteran Barney Pelty to the mound. Pelty, who would spend nine years of his 10-year major-league career with the Browns, was 11-11 with a 2.30 ERA in 1909. Tommy Connolly umpired behind the plate while Bill Dinneen handled the field.

The Browns’ George Stone, known for his small crouch at the plate, led off with a double to left, the first hit in Comiskey Park history, and Roy Hartzell sacrificed him to third. Bobby Wallace grounded to second baseman Rollie Zeider, who threw home. Stone was tagged out in a rundown. During the rundown, Wallace took off for second but was beaten by a strong throw by Sullivan.

The clubs remained scoreless until St. Louis scored both of its runs in the third inning. Frank Truesdale reached when third baseman Billy Purtell could only deflect his scorching grounder. Purtell had to decide to “let it go by or lose a hand. Billy decided to keep the hand,” Harry Daniel wrote.12 Truesdale stole second and made his way to third on a groundout. Stone smashed Walsh’s first pitch for a single along the left-field line, scoring Truesdale with the first run in the park’s history. The new turf was troublesome for Patsy Doherty in left, as he “slipped and slid around like a man who is afraid to go home in the dark,” wrote Daniel. Doherty finally threw the ball in as Stone dug for second. He slid hard, spiking Zeider’s hand, knocking the ball free and forcing the rookie second baseman to leave the game, replaced by Charlie French. (Zeider would miss a couple of weeks.) Hartzell walked and Stone scored when Sullivan attempted to pick off Hartzell but threw “over Chick] Gandil’s upstretched anatomy.”13 Hartzell tried for third on the play but was thrown out by Shano Collins.

The Browns tried to tack on more runs in the fourth against Walsh. Bobby Wallace singled to right and scampered to third on Pat Newnam’s hit. Walsh came back, striking out Al Schweitzer and Danny Hoffman. Wallace was nabbed at the plate in an attempted double steal with Newnam, and an opportunity was wasted.

Chicago had more problems with the new turf as Sullivan “fell headlong over some new laid sod” that snagged his spikes while he was attempting to corral a foul popup.14 The tough-luck catcher avoided serious injury, but the same couldn’t be said for the battered sod, which the Chicago Examiner said was the size of a washtub.15

In the fifth, Chicago’s George Brown brought the crowd to its feet with a spectacular diving catch. “It is too bad for Browne that high dives do not figure in the percentage column,” wrote Daniel.16 He was a century too early, it seems.

Pelty had allowed Chicago only two singles through six innings, both by rookie Lena “Bearcat” Blackburne, the first two Chicago hits in the history of Comiskey Park. The crowd finally had something to cheer about when Doherty slammed a triple to deep right. But Gandil was retired on a roller in front of the plate and the eager Doherty was thrown out at the plate when he tried to score on a “skimpy infield hit” by Purtell. “That was about as dangerous as those White Sox ever got on the first day in their new park,” Daniel commented.17

Stone led off with a triple to right in the ninth, but Hartzell flied to Browne, and Stone had to hold at third. Wallace struck out, and when Stone tried to sneak home on a passed ball, he was thrown out, ending the game.

Pelty finished the game for the Browns, striking out three of his total five in the last two innings, scattering only five hits as he spoiled the White Sox’ new home opener, 2-0. Walsh struck out six and allowed seven hits, with Stone (single, double, and triple, run, RBI) being the hitting star of the game.

Comiskey invited several of the out-of-town guests already mentioned, as well as Chicago baseball legends Cap Anson and Frank Isbell, to a banquet at the Chicago Automobile Club that evening.

“The game was distinctly not the thing yesterday,” quipped the Tribune. As Sanborn appropriately wrote, it was “Charles A. Comiskey’s big housewarming party.”18

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted the following:

Baseball-reference.com.

Dryden, Charles. “Sox Open New Park With 2-0 Defeat by Browns Before 30,000,” Chicago Examiner, July 2, 1910: 10.

Retrosheet.org.

Notes

1 I.E. Sanborn, “Commy to Greet Sox Fans Today,” Chicago Tribune, July 1, 1910: 12.

2 I.E. Sanborn, “Big Army of Fans Greets ‘Commy,’” Chicago Tribune, July 2, 1910: 10.

3 “New Park Awaits Fans’ Onslaught,” Chicago Tribune, June 30, 1910: 12.

4 Ibid.

5 “Commy to Greet.”

6 “Big Army of Fans.”

7 Ibid.

8 Harry Daniel, “30,000 Hail Sox in Modern Arena; Browns Win, 2-0,” Chicago Inter-Ocean, July 2, 1910: 13.

9 “Ten Die of Heat as City as City Sizzles,” Chicago Tribune, July 2, 1910: 1.

10 With a minimum of 1,000 innings pitched.

11 Trey Strecker, “Billy Sullivan Sr.,” SABR BioProject. https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/d0d341b0 Retrieved November 22, 2017.

12 Daniel.

13 Ibid.

14 Ibid.

15 “Notes of the Sox,” Chicago Examiner, July 2, 1910: 10.

16 Daniel.

17 Ibid.

18 “Big Army of Fans.”

Additional Stats

St. Louis Browns 2

Chicago White Sox 0

White Sox Park

Chicago, IL

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.