July 1, 1943: All-American Girls play first game under the lights at Wrigley Field

Members of the Kenosha Comets of the All-American Girls Base Ball League pose for a photo on July 1, 1943, at Wrigley Field in Chicago. (Chicago Sun / GenealogyBank.com)

Philip K. Wrigley, chewing-gum magnate and longtime owner of the Chicago Cubs, was an innovator and experimenter, and during World War II, he was committed to supporting the war effort.1 For instance, he assigned all his radio time to selling the war rather than gum — $2 million for two CBS programs alone. He also converted part of his gum-packing factory into an assembly line for packing K rations; and he directed his gum tappers in Central and South America to tap as many rubber trees as they could while working on gum trees.2

Thus, in the late fall of 1942, when the War Department notified major-league baseball owners that the 1943 season might have to be postponed because of increasing manpower needs, Wrigley approved and funded his committee’s recommendation to organize a women’s professional softball league to fill the possible void in major-league parks, to keep baseball alive, and to provide entertainment for war workers and service personnel.3 He reasoned:

“World War One showed to the world for the first time on a large scale what women could and did do, and World War Two is going to carry this even further. American women have taken a very definite share of the load in the country’s progress, and in the fields of science, business and sports they are now also working in ever increasing numbers.”4

Originally Wrigley named the new professional league the All-American Girls Soft Ball League (AAGSBL), but he changed that title to the All-American Girls Base Ball League (AAGBBL) in midseason 1943, because except for the 12-inch ball, the shorter field distances, and underhand pitching, the playing rules he instituted were those of baseball.5

Wrigley established the AAGBBL with some experimental policies:

- He established the league on a nonprofit, trusteeship basis to provide entertainment for service personnel and war-factory workers in cities near Chicago.

- He recruited the most skilled players in the United States and Canada.

- Player contracts belonged to league administration instead of individual teams to facilitate equalized competition through a player allocation board.

- He established strict, college-based rules of on- and off-field behavior.6

Major-league baseball survived the manpower push of 1943, and as the team owners had done in 1942, they earmarked the proceeds of the 1943 regularly-scheduled June 30 and July 18 games, as well as the July 13 All-Star Game, to go to various war-relief agencies as part of their contribution to the war effort. Most of the proceeds from these games benefited servicemen.7

The fact that Wrigley hosted a large Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) rally in Wrigley Field the night after the June 30 benefit game confirms that considerable planning and coordination took place between Wrigley and Army commanders stationed in the Chicago area. Wrigley’s efforts aimed to benefit servicewomen.

A league newspaper noted that an intensive WAAC recruiting push was underway to enlist 30,000 new WAACs by July 1, 1943, because each WAAC recruit freed a serviceman for combat duty. The “mammoth” WAAC program at Wrigley Field the night of July 1, 1943, contributed to this effort and included the following:8

- A WAAC softball game between a Camp Grant team (near Rockford, Illinois) and a Fort Sheridan team (on Lake Michigan north of Chicago).

- WAAC entertainment including military drills, calisthenics, a band performance, and a uniform display.

- Recruiting talks by members of the 6th Service command.

- At least 150 WAACs circulating in the stands to answer questions.

- An All-Star AAGBBL game with ballplayers from the four original league teams (Racine Belles, Kenosha Comets, South Bend Blue Sox, and Rockford Peaches) to cap off festivities.9

Scheduling the WAAC softball game at 6:00 P.M. enabled more working women to attend. Making the event free of charge coincided with the league’s nonprofit status and possibly enabled young women unable to attend otherwise to participate. In addition, the 8:30 P.M. AAGBBL game provided Wrigley with an opportunity to experiment with a night game at his ballpark. Interestingly, Wrigley experimented with the first-ever twilight game at Wrigley Field on June 26, 1943, between the Cubs and Cardinals, and it may have been a test run for the upcoming WAAC rally.10

To help involve AAGBBL fans in the WAAC rally and AAGBBL All-Star Game, sportswriters in the league’s cities advised them that the Chicago league office requested their votes to determine the All-American All-Stars. Sportswriters also advised fans that those who submitted ballots would receive a free ticket to a local game11

Apparently, local AAGBBL fans turned in a considerable number of ballots. A Rockford sportswriter reported the following:

A flood of votes, mailed last night [June 29] just before the midnight deadline descended on the Register Republic sports department today and were turned over immediately to league officials who said that they had been making an attempt to summarize the local vote but had been unable to keep up with the flow of ballots.12

In pregame publicity, the Rockford Morning Star introduced the Camp Grant team with a team photo on the sports page and noted their “Nifty Uniforms.” The photo revealed the surprising fact that the Camp Grant team uniforms were identical to the AAGBBL skirted uniforms!13

In South Bend, fans learned that league officials recruited Joe Boland, the public-address announcer for their Blue Sox, to serve as the field announcer for the WAAC rally at Wrigley Field.14

Postgame publicity on July 2, 1943, recorded that 7,000 fans attended the WAAC rally, and that the Fort Sheridan WAACs defeated the Camp Grant team, 11-5.15

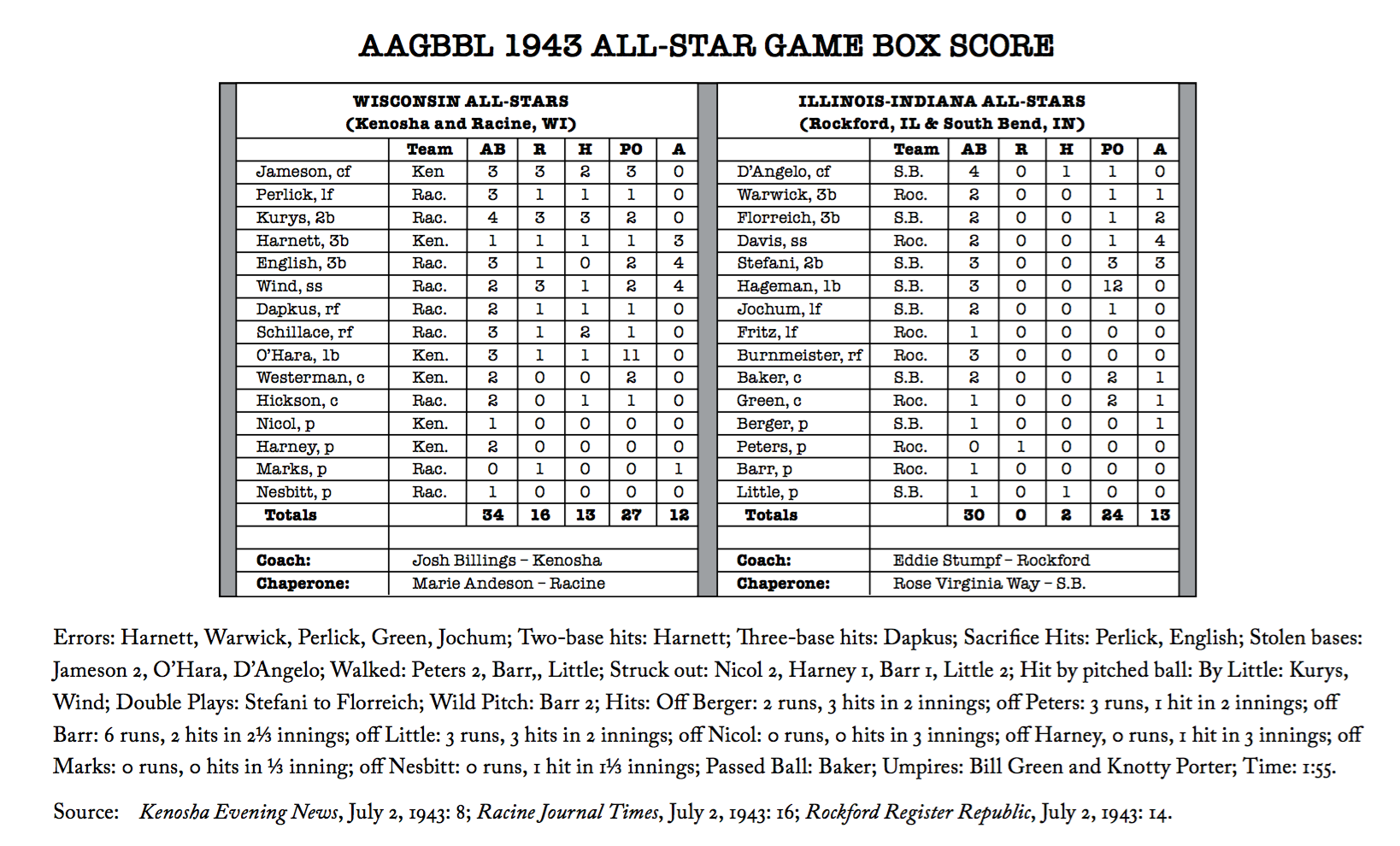

The AAGBBL game began with the teams’ usual wartime, pregame routine of lining up in a V-for-Victory formation during the national anthem. The game itself proved to be a one-sided affair with the Wisconsin All-Stars trouncing the Indiana-Illinois All-Stars, 16-0. Apparently, it was one of those nights when one team could do no wrong, and the other team couldn’t do much.16

Three banks of temporary lights were installed on poles situated behind home plate, first base, and third base. One sportswriter judged them suitable for softball.17 Researcher Jay Feldman recorded players’ recollections of playing under those lights:

Shirley Jameson: “The lights weren’t all that great, but we were used to that – we had to play with whatever we had. Besides, just the fact that we were playing in Wrigley Field was enough. We’d have done it whether it was light or dark, because we were all on Cloud Nine.”

Mildred Warwick echoed Jameson’s sentiments about playing in Wrigley Field: “All of a sudden I’d landed in Wrigley Field. I was overwhelmed by the size of it, and I thought, ‘Oh my goodness, I’m playing in Wrigley Field.’ I was thrilled.”

Pitcher Helen Nicol noted that the lighting conditions challenged the outfielders: “The shadows would come up and all of a sudden you wouldn’t be able to decipher where the ball was. It was pretty hard for the outfielders to see, especially if the ball got up high.”

Betsy Jochum didn’t realize she was part of a historic event: “I didn’t realize at the time that they didn’t have lights at Wrigley Field. … I just thought those lights were there all the time. We showed up for the game, the lights were on, and we played.”18

AAGBBL sportswriters’ recaps recognized the game’s outstanding players and events:

“… the brilliant outfielding and baserunning of Shirley Jameson, Kenosha center fielder, thrilled the big crowd throughout the game.19

Eleanor Dapkus hit a triple with the bases loaded to drive in three Wisconsin runs.20

Sophie Kurys got three singles in four trips and drove in two runs besides scoring three herself. Dorothy Wind scored three runs and got one hit in two official turns at bat. Clara Schillace had two hits in three tries.21

Gloria Marks was hit by a line drive and forced to retire after pitching just two-thirds of an inning. Mary Nesbitt pitched the last 2⅓ innings and got in just enough work to sharpen her pitching for tonight.22

Helen Nicol, Kenosha hurler from Calgary, Canada, pitched no-hit ball during her three-inning effort and a teammate, Elise Harney, of Jacksonville, Illinois, was nicked for the first Illinois-Indiana hit when Josephine D’Angelo singled after two out in the seventh inning. The other hit by the losers was pitcher Olive Little’s infield hit to open the ninth.”23

Sportswriters didn’t provide a WAAC box score, but they did provide the AAGBBL’s:

(Click image to enlarge)

So ended the “mammoth” July 1, 1943, World War II WAAC rally, which incorporated the historic first-ever lighted night game at Wrigley Field. It provided Philip Wrigley an opportunity to benefit women service personnel and to experiment with a night game. The players were thrilled to play in a major-league park and Wrigley Field in particular. At the time, none of Wrigley’s women players imagined they had just made history that would be repeated once more by their league in 1944 and not again until the Cubs played a night game at Wrigley Field in August 1988 — 44 years later.

This article appears in “Wrigley Field: The Friendly Confines at Clark and Addison” (SABR, 2019), edited by Gregory H. Wolf. To read more stories from this book online, click here.

Notes

1 Merrie A. Fidler, The Origins and History of the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Company, 2006), Chapter 1.

2 “Chewing Gum Is War Material,” Fortune, January 1943: 100.

3 Kenosha Evening News, May 27, 1943, 16; June 1, 1943: 9.

4 “Mr. Wrigley’s Statement for the Press on the Girls’ All-American Softball League,” February 17, 1943, Arthur Meyerhoff Files, drawer 19, 1943 News Release Folder.

5 Fidler, 36.

6 Fidler, 34-36.

7 “Majors to Put on Big Show for War Benefit Wednesday,” Racine Journal Times, June 19, 1943: 10.

8 Carl E. Lundquist, “News Views,” Rockford Morning Star, June 15, 1943: 2; “All-American Girls’ Softball League Play All-Star Contest for WAACs,” Kenosha Evening News, June 24, 1943: 8.

9 Chicago Tribune, July 1, 1943: Section 2, 21; “Belles to Play Sox Tonight,” Racine Journal Times, June 30, 1943: 10.

10 “Redbirds Lose Fourth Time to Puerto Rican,” Boise Idaho Statesman, June 26, 1943: 7.

11 See sports pages of the Rockford Register Republic, the Kenosha Evening News, the Racine Journal Times, and the South Bend Tribune between June 23 and June 29, 1943; “Big Vote Cast for All-Stars,” Rockford Register Republic, June 30, 1943: 15.

12 Rockford Register Republic, June 30, 1943: 15.

13 Rockford Morning Star, June 27, 1943: 35.

14 “Jim Costin Says,” South Bend Tribune, June 24, 1943: 8.

15 “Wisconsin Girls Win, 16-0 on WAAC Program,” Chicago Tribune, July 2, 1943: 21.

16 Racine Journal Times, June 30, 1943: 10; “Peaches Meet Kenosha Again,” Rockford Register Republic, July 2, 1943: 14.

17 “Cook to Face Nicol Tonight When Peaches Tackle Kenosha,” Rockford Register Republic, June 29, 1943: 10.

18 Jay Feldman, “The Real History of Night Ball at Wrigley Field,” Baseball Research Journal, Society for American Baseball Research, No. 21, 1992: 93-95.

19 “Blue Sox Fight to Retain Lead,” South Bend Tribune, July 2, 1943: Section 3, p. 1.

20 “Belles to Play Sox Tonight; Seek Lead,” Racine Journal Times, July 2, 1943: 16.

21 Ibid.

22 Ibid.

23 “Wisconsin Team Triumphs, Comets Star,” Kenosha Evening News, July 2, 1943: 8.

Note on Sources: The Rockford Morning Star and Boise Idaho Statesman, were accessed through genealogybank.com.

Additional Stats

Wisconsin All-Stars 16

Illinois-Indiana All-Stars 0

Wrigley Field

Chicago, IL

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.