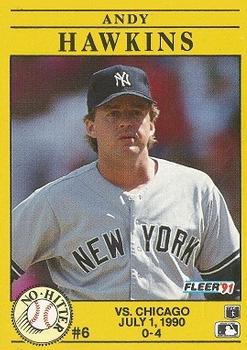

July 1, 1990: Andy Hawkins no-hitter is ‘no winner’ for Yankees

In 1906 the Chicago White Sox won the World Series with a team called the Hitless Wonders. On July 1, 1990, the White Sox truly were hitless but still victorious.

In 1906 the Chicago White Sox won the World Series with a team called the Hitless Wonders. On July 1, 1990, the White Sox truly were hitless but still victorious.

The 80th anniversary of Comiskey Park that day was also its last. Across the street to the north, a new Comiskey Park was rising and visible above the roof of the existing ballpark.

It was also Bat Day, an event that caused a delay in getting fans into the park. The gates were not opened until barely an hour before game time because the souvenir bats were late in arriving; the bats handed out to the kids were not the only ones slow in showing up.1

Andy Hawkins of the New York Yankees and Greg Hibbard of the White Sox combined to retire the first 29 batters in the game. Hibbard took a perfect game into the sixth before allowing a pair of one-out infield hits; he made it through seven innings without allowing a run but ended up as the forgotten man in the game.

Hawkins was making the most of a reprieve from a month before. With a won-lost record of 1-4 in early June, he was given the choice of a demotion to the minors or a release; he chose the latter. However, Mike Witt injured his elbow the next night, and Hawkins stayed with the Yankees. By the end of June, he was still winless over nearly the last two months although he had been pitching better, just without good fortune. His luck didn’t improve with the coming of a new month.2

As Hibbard cruised through the opening innings, Hawkins put down the first 14 hitters he faced before walking a pair in the fifth. Sammy Sosa then crushed a ball to left that surely meant the end of the no-hitter and shutout — except that a stiff wind from the north kept the ball in and moved it toward the left-field line, and Jim Leyritz corralled it on the warning track to end the inning. The USA Today box score listed the game-time weather as 70 degrees with the wind at 16 miles per hour.3 What this information didn’t convey was how the wind swirled inside the ballpark, a challenge for fielders that would become a factor a few innings later.

The game was still scoreless, and the White Sox still hitless, with two out in the eighth when Sosa hit a grounder to third. Mike Blowers tried to backhand the ball, knocked it down, and then threw too late to get a sliding Sosa at first. A novice scoreboard operator jumped the gun and immediately flashed a hit on the board.4 But official scorer Bob Rosenberg hadn’t even had the chance to rule on the play; when he did, it was an error.

Many thought he had first called a hit and then changed it to an error, but Rosenberg said, “I called it [an error] right away. The Yankees in the dugout were giving me the finger,” he said of what happened before the correct decision made it onto the scoreboard.5

Hawkins didn’t remember any obscene gestures directed toward Rosenberg, but he did see waving and “commotion over there in the dugout.” He thought his no-hitter was gone, but “the next thing I know I hear this cheer go up [an indication of the error finally being flashed on the scoreboard], so I went from, ‘Oh, it’s over’ to ‘I gotta get it back going again.’”6

The scoring decision finally set straight, the game continued. Sosa stole second, and Hawkins walked the next two hitters, causing stirring in the New York bullpen and a mound visit from manager Stump Merrill.

Hawkins got Robin Ventura to lift a fly to left. Leyritz followed the ball through the wind, found the range, and then had the ball hit off his glove and roll into the corner. Three runs scored as Ventura pulled into second. Suddenly Hawkins went from needing three outs for a no-hitter to just one out, since the error meant the White Sox would probably not be batting in the ninth.

It looked as if he had his out as Ivan Calderon hit an easy fly to right. But Jesse Barfield, battling the sun, had the ball pop in and out of his glove for another error as Ventura scored. After Hawkins retired Dan Pasqua on a pop fly to short, he walked off the mound with a no-hitter — albeit down by four runs — as the fans gave him an ovation. The game ended a few minutes later as the Yankees went down in the ninth.

Ironically, the two outfield butchers who cost Hawkins the game were also the two who made his no-hitter possible with fine catches to start the game. Leyritz charged and slid to make a shoestring catch of Lance Johnson’s blooper leading off the bottom of the first. Barfield then ran and leaped to catch a shot hit by the next batter, Ventura.

The Sunday no-hitter by Hawkins was the third of the weekend in the majors. Two nights before, Dave Stewart of the Athletics and Fernando Valenzuela of the Dodgers had hitless outings, with different outcomes than Hawkins. “This is not even close to the way I envisioned a no-hitter would be,” Hawkins told Michael Martinez of the New York Times after the game. “You dream of one, but you never think it’s going to be a loss. You think of Stewart and Fernando, coming off the field in jubilation. Not this.”7

Pitching a no-hitter and losing is a rare event. Ken Johnson had this happen to him in 1964. Of Hawkins, Johnson said, “I’m sorry to hear he joined me. I was very happy being the only man to lose a no-hitter.”8

However, Johnson had not been alone in this distinction. Baltimore pitchers Steve Barber and Stu Miller combined on a losing no-hitter for Baltimore on April 30, 1967, and there was one other game that resembled the one pitched by Hawkins. In the Players League in 1890 Charles “Silver” King of Chicago no-hit Brooklyn but lost 1-0, a result that meant that King, like Hawkins, pitched only eight innings because Brooklyn did not have to bat in the bottom of the ninth. (Since Hawkins, there have been two other of these eight-inning-type no-hitters.)

“If Comiskey II, currently under construction across 35th Street, lasts another 80 years, it will not house a stranger game,” wrote Bill Jauss in the Chicago Tribune.9

Hawkins’s struggles continued beyond the bizzaro in Comiskey I. He didn’t win again until late July. Not only that, in the meantime, he was the losing pitcher in another no-hitter with the White Sox, this one by Chicago’s Melido Perez although the game was called by rain in the top of the seventh on July 12.

Rain-shortened no-hitters such as these usually weren’t considered as “real” no-hitters by sentiments of the time. But no-hitters in games played to their natural conclusion were treated with the lofty status of others, even if the pitcher went only eight innings.

However, the next year Hawkins’s game was dropped from the list of “official” no-hitters by a committee fiat because he had pitched fewer than nine innings.

Regardless of the ruling of a committee, his great pitching and bad luck created far more of a buzz than just about any official no-hitter. The game story made the top of the front page (not just the front sports page) in USA Today with the headline “Yankee’s no-hitter is no winner” and a jump to the sports section for more on this “Unbelievable game.”10 The game led sportscasts and also had prominence on regular news programs.

On the 25th anniversary of the game, Grant Brisbee in SB Nation chronicled the event in words and video, making clear that this was a no-hitter like no other.11

This article was published in SABR’s “No-Hitters” (2017), edited by Bill Nowlin. To read more Games Project stories from this book, click here.

Notes

1 Memory of the author, who attended this game.

2 Michael Martinez, “Hawkins lucky to be around for this one,” New York Times, July 2, 1990: 3E.

3 USA Today, July 2, 1990.

4 Bob Logan, “Scoreboard operator makes biggest error in White Sox’ win,” Arlington (Illinois) Daily Herald, July 2, 1990: section 4, page 8.

5 Telephone interview with Bob Rosenberg, August 1, 2015.

6 Author interview with Andy Hawkins, August 12, 2015. Until this interview, Hawkins was not aware that the errant decision on the scoreboard was the result of an incompetent operator and not the result of the official scorer first ruling a hit and then changing it to an error.

7 Michael Martinez, “Hawkins hurls no-hit gem, but Yanks blow it.” New York Times, July 2, 1990: 1E.

8 “An asterisk for the books,” Minneapolis Star Tribune, July 2, 1990: 1C.

9 Bill Jauss, “Sox’s hitless victory a real wonder,” Chicago Tribune, July 2, 1990: section 3, page 1.

10 Mel Antonen, “Yankee’s no-hitter is no winner,” USA Today, Monday, July 2, 1990: 1A.

11 Grant Brisbee, https://sbnation.com/2015/7/1/8841355/andy-hawkins-no-hitter-yankees-white-sox. Brisbee gets a few facts wrong (such as the claim of Hawkins striking out 17 in the game — it was 3 — and on the number of pitches it took for Hawkins to retire the first two batters in the bottom of the eighth), but his tone is appropriate for conveying the significance of this no-hitter. For the record, the author’s scorebook shows that Hawkins retired the first two batters in the eighth on 10 pitches (not 14, as claimed by Brisbee), and the scorebook showing of 131 pitches in the game for Hawkins (including 37 in the eighth inning) is consistent with the total listed by USA Today in its box score the next day.

Additional Stats

Chicago White Sox 4

New York Yankees 0

Comiskey Park

Chicago, IL

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.