July 10, 1901: Harry Davis becomes first American League player to hit for the cycle

The year was 1901, the inaugural season of the new American League. The sixth-place Philadelphia Athletics visited the top-spot Boston Americans on a Wednesday afternoon game at the Huntington Avenue Grounds. Boston was riding a seven-game win streak and since June 4 had won an amazing 25 of 29 contests. On the other hand, the Athletics had managed to win only three of their last 16 games (there was one tie, and they had lost nine straight to start the streak).

Boston management announced a ladies day promotion, and approximately 5,000 fans took to the ballpark; of that number, at least 400 were women. According to the Philadelphia Inquirer, “It was a superb day for the national pastime.”1 The game provided plenty of offense, and “the Athletics got themselves together and put the kibosh on the leaders in grand style.”2 Ban Johnson, president of the American League, was on hand to see the action. The Boston Globe reported that Johnson “sat in the pavilion with a party of friends who enjoyed the hard hitting.”3 Where the Philadelphia newspapers reported that the game was full of action, the hometown Boston Post described the game as “the sleepiest and longest-drawn-out contest of the season at the Huntington avenue grounds.”4 The crowd was treated to a rare event by Philadelphia’s Harry Davis, who became the first player in the American League to hit for the cycle.

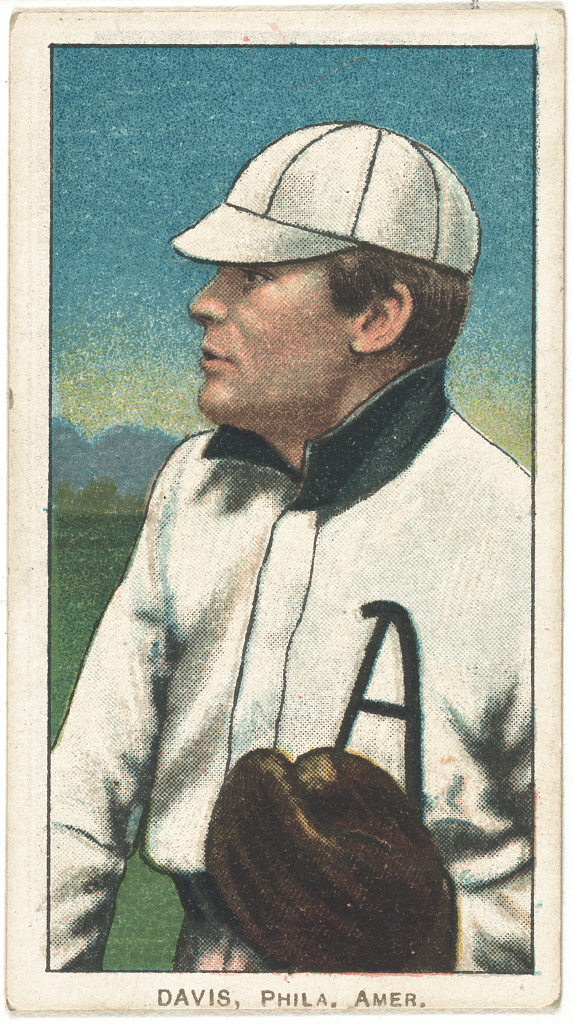

Born in Philadelphia on July 18, 1873, Harry Davis became a major leaguer in 1895, getting an offer from the New York Giants. Over the next four seasons, he bounced from New York to the Pittsburgh Pirates to the Louisville Colonels to the Washington Nationals. Because of leg injuries, he spent much of the 1899 season (110 games) and all of 1900 (135 games) out of the National League, instead playing for Providence in the Eastern League. As the 1901 season began, Davis quit baseball and returned to his hometown of Philadelphia to work for the Pennsylvania Railroad.5 Athletics manager Connie Mack contacted Davis (Davis had played for Mack in Pittsburgh), offered him a spot on the roster and signed the slugger to his team on May 21, 1901. Davis became a starter, playing 117 games at first base. He anchored the Philly infield for the next 10 seasons.6

Philadelphia’s Chick Fraser faced off against Boston’s Ted Lewis on the mound. Both right-handers had played for their same city’s National League team in 1900 (Fraser for the Phillies and Lewis for the Boston Beaneaters).

The visitors scored in the top of the first. With one out, Davis sent a triple into right field. Lave Cross brought him home with a single. Nap Lajoie followed with a single, and Socks Seybold drew a walk to load the bases. Lewis walked Matty McIntyre, forcing Cross home, and then a passed ball charged to Boston catcher Lou Criger allowed Lajoie to touch the plate.

Boston got three runs in the bottom of the first. Tommy Dowd led off with a double to left. Chick Stahl walked. An out later, Buck Freeman singled, driving in Dowd and sending Stahl to third. The Americans then pulled a successful double steal (Stahl scored). The final run of the inning was produced when Hobe Ferris hit a two-out single, plating Freeman, to tie the score, 3-3.

The Athletics took the lead in the third inning. Lajoie singled into the hole between short and third and moved to second base on third baseman Jimmy Collins’s wild throw. Lajoie scored on a hit by Doc Powers. But again, Boston answered with its own tally, manufacturing a run on a Collins walk, a groundout to move up the runner, and an RBI single by Charlie Hemphill.

Both teams scored in the fourth. Davis, who had singled in the second, smacked a home run for Philadelphia, sending the ball “to the very end of right field.”7 He raced around the bases for an inside-the-park round-tripper. In the home half, Freddy Parent doubled, advanced to third on a fly ball, and scored when Criger singled.

The scored remained tied until the sixth inning, when the game became “irretrievably lost”8 for the Americans. “Lewis’ Waterloo”9 started when he walked Fraser and Dave Fultz. Davis then socked a double to right, scoring Fraser. Hemphill juggled the ball, and Davis continued to third as Fultz scored. Cross singled, bringing in Davis. After Lajoie fanned, Seybold “pushed a safe fly over second”10 and Cross scored, giving the Athletics a four-run advantage and ending the day for Lewis.

Fred Mitchell entered the game in the seventh, relieving Lewis. He immediately walked Joe Dolan. Fraser singled, with Dolan motoring to third base. Two outs later (one by Davis), Cross pushed a double to right field, driving in Dolan. Two more runs came home for Philadelphia in the eighth. Seybold walked and advanced to second on McIntyre’s grounder. Then Mitchell plunked Powers, putting runners at the corners. Dolan grounded a ball to shortstop Parent, who threw the ball to catcher Osee Schrecongost (he had relieved Criger when the latter injured a finger on a foul tip), but the catcher dropped the ball, and Seybold was safe. The Athletics added another run when a grounder was hit to second baseman Freeman who threw to first instead of trying for a double play.11 Philadelphia now led by seven runs.

Boston added its last run in the bottom of the eighth on two singles and a passed ball. In the final frame, Philadelphia attacked again. Davis singled and scored on Seybold’s two-out triple. That was all the scoring, as Philadelphia triumphed, 13-6.

With his 5-for-6 performance, Harry Davis became the first American League batter to hit for the cycle, collecting “a sample of everything — a home run, three-bagger, two-bagger and [two] singles.”12 In addition to Davis’s batting display, “Larry Lajoie got singles in his first three times up, in each instance hitting the first ball pitched.”13 Parent led the Boston offense with a double and two singles.

The loss dropped Boston into second place in the American League. The Americans never got back into first. In taking the loss, Lewis “gave one of those see-saw exhibitions, one alternating with effective and wretched twirling.”14 Although he notched seven strikeouts, he also allowed five bases on balls, one of which forced in a Philadelphia run. The Boston Globe told its readers that “Lewis did some good work, but was always in a hole.”15 Fraser was a bit wild, but he did earn the win for the Athletics. In pitching a complete game, he struck out three, walked three, hit a batter, and was charged with a wild pitch.

Five seasons had come and gone since Washington’s Bill Joyce hit for the cycle against the Pittsburgh Pirates (May 30, 1896). This five-season stretch is the longest period in the major leagues in which no batter hit for the cycle. Two other batters in addition to Davis hit for the cycle in 1901, and both rare feats were also accomplished in July. Pittsburgh’s Fred Clarke did it on July 23 against the Cincinnati Reds, and a week later, on July 30, Davis’s teammate Nap Lajoie hit for the cycle against the Cleveland Blues.

Although Davis was the first American League player to hit for the cycle, four other Philadelphia Athletics had done it when the A’s played in the American Association. They were Lon Knight (July 30, 1883, who hit for a natural cycle against the Pittsburgh Alleghenys), Henry Larkin (June 16, 1885, also against the Alleghenys), Chippy McGarr (September 23, 1886, against the St. Louis Brown Stockings), and Harry Stovey (May 18, 1888, against the Baltimore Orioles).

Sources

In addition to the sources mentioned in the Notes, the author consulted baseball-reference.com, mlb.com, retrosheet.org and sabr.org. Play-by-play comes from the newspaper accounts cited in the Notes. There are no links to box scores.

Notes

1 “Athletics Take a Large Fall Out of Boston,” Philadelphia Inquirer, July 11, 1901: 7.

2 Ibid.

3 “Baseball Notes,” Boston Globe, July 11, 1901: 5.

4 “Quakers Found Boston Easy,” Boston Post, July 11, 1901: 3.

5 Mike Grahek, “Harry Davis,” sabr.org/bioproj/person/61ebb0fe. Accessed February 2019.

6 With the exception of 1912 (when he played for Cleveland), Davis spent the rest of his career (16 years), playing for Connie Mack and the Athletics, batting .279. From 1911 through 1917, he played in only 78 games.

7 “Lewis Always in the Hole,” Boston Globe, July 11, 1901: 5.

8 Ibid.

9 Ibid.

10 Ibid.

11 Ibid.

12 Boston Post.

13 “Lewis Always in the Hole.”

14 Boston Post.

15 “Lewis Always in the Hole.”

Additional Stats

Philadelphia Athletics 13

Boston Americans 6

Huntington Avenue Grounds

Boston, MA

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.