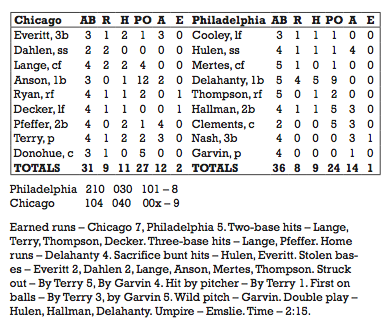

July 13, 1896: Ed Delahanty’s four-home run game

The Philadelphia Phillies had high hopes for the 1896 season. It was hoped that Billy Nash, acquired in a trade from Boston to be the new third baseman and manager-captain, could bring teamwork and playing fundamentals to the talent-laden team. The ballclub also signed Big Dan Brouthers to play first base. But after a good start, their pitching soured and the team lost eight straight games. From May 11 to the end of June the club went 16–24. One writer suggested that the team looked like they were “dosed on morphine.”1

A closer look revealed a troubled team. Nash was beaned and could not play. Brouthers played poorly and was dropped after a salary dispute. Injuries and illnesses laid up Jack Clements, Al Orth, Lave Cross, and Con Lucid. The most troubling injury was to Ed Delahanty, who had reinjured his old separated shoulder. At one point he was hospitalized and missed eight games. Yet when the Phillies departed for Cincinnati after a July 4 doubleheader, Ed was in the midst of a 19-game hitting streak. He ultimately batted safely in 27 out of 28 games.

Despite Delahanty’s effort, the ball club did not improve its standing, arriving in Chicago 0-for-6 on the road trip including three losses to last-place Louisville. The city, which had just hosted the Democratic Party convention that nominated William Jennings Bryan for president, gave little thought to the Monday afternoon midsummer ballgame. A heat wave that recorded 133 deaths the day of the game also hurt interest, and only about 1,000 hardy fans turned out at West Side Park. The thermometer in the grandstand read in the triple digits.

The Phillies started a lanky rookie hurler, Virgil Garvin. He was opposed by the veteran William “Adonis” Terry. This handsome right-handed curveball specialist had already won more than 180 major- league games. Delahanty had had previous success against the clever offspeed Terry, with 16 hits in 48 at-bats for a .333 average. But he had never hit a home run off Terry.

The ballpark that hosted this memorable game was oddly fashioned. The foul lines were 340 feet to the perimeter fence, and the on-field clubhouses in center field were more than 450 feet from home plate. The right-field wall was 40 feet high with a scoreboard and a canvas screen fastened to telephone poles in order to block the view of rooftop spectators. It was an unlikely setting for the greatest hitting performance of the 19th century.

The Phillies began the game with Duff Cooley getting a walk and being sacrificed to second base. With two outs, Delahanty, batting fourth in Dan Brouthers’ former spot, swung at an outside pitch and hit it over the inner, lower bleacher fence in front of the right field wall. Jimmy Ryan chased the ball into the narrow bleachers between the two fences as Cooley and Delahanty scored. In the third inning, Ed hit a vicious line drive toward shortstop that knocked over the leaping Bill Dahlen and went into left field for a single. Del’s third at bat came with two runners on base. This time he struck a towering blow that soared over the scoreboard and canvas-topped right-field wall. It landed across the road in a flock of chickens. A young boy picked up the ball and was chased by a panting policeman. This home run was said to be the longest ever hit at West Side Park.

With the Phillies losing, 9–6, Delahanty came to the plate in the seventh inning. He swatted a fastball that went over the head of the fleet-footed Chicago center fielder, Billy Lange. The ball rolled to the distant clubhouses, giving Delahanty his third home run. When Delahanty came to bat in the ninth inning, fans had forgotten the score and were cheering for another home run. Chicago manager Cap Anson threatened to fine his whole team “the price of three meals at World Fair rates” if any Philadelphia player was put on base before Delahanty got his last at bat.2 To make sure everything was in order, center fielder Lange called time and retreated to the farthest part of the grounds—the uncut grass before the centerfield clubhouses. Delahanty, in his soaking-wet woolen uniform, laughed at the spectacle of the retreating center fielder.

With Chicago fans behind him, many standing on their seats, Delahanty fooled everyone and bunted the first pitch foul. His action brought shouts from the grandstands: “Line it out, Del!” Ed enjoyed this stunt and waited on Terry’s next pitch, a slow, outside curve. The bat, it was reported, impacted with the sound of a “rifle shot.” The hit carried over 450 feet, beyond Lange, and bounded onto the roofs of the center-field clubhouses. Delahanty easily scored his fourth home run without a throw. As he crossed the plate, Terry was waiting to shake his hand. Outfielder Lange hid the ball under the clubhouse for a souvenir, and the fans remained standing on their seats cheering wildly for about 10 minutes. After the game, spectators followed Del to the omnibus and offered him congratulatory claps on his back. A local gum factory recognized Ed’s achievement by giving him a box of gum for each home run. One Chicago paper wrote that if it were not for Delahanty’s hitting the overheated fans would have “cursed the day baseball was invented.”3

The Phillies lost the game, 9–8, their seventh setback in a row. Ed had five of the team’s nine hits. He knocked in seven runs and had 17 total bases. That evening, back at the hotel, many commiserated with Delahanty. They told him it was a tough loss after the way he batted. Ed replied, “I did the best I could. I couldn’t hit any more.”4 Queried about “Adonis” Terry, Delahanty confessed that he never hit hard against him, but “Today they came just right. Tomorrow I probably would not get a hit. Those things can’t be explained.”5

Before Delahanty, only Boston’s Bobby Lowe, in 1894, had hit four homers in a game. Nothing again rivaled Delahanty’s power display until Lou Gehrig hit four cork-centered baseballs out of Philadelphia’s Shibe Park in 1932.

Delahanty finished the year with 13 home runs and 126 RBIs. In a Sporting Life feature, he was praised: “Amid the wreck of the year the performance of Delahanty shines out luminously and marks him as indeed the star of the team.”6

Notes

1 Philadelphia Inquirer, June 3, 1896, June 10, 1896.

2 Randall Papers (Letters and Papers of Norine Delahanty, Mobile, Alabama), packet one.

3 Randall Papers, packet two.

4 Sporting Life, August 1, 1896, August 8, 1896; Philadelphia Inquirer, August 2, 1896.

5 Sporting Life, July 14, 1896.

6 Sporting Life, August, 22, 1896, October 17, 1896.

Additional Stats

Chicago Colts 9

Philadelphia Phillies 8

West Side Park

Chicago, IL

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.