July 15, 1876: Wearin’ of the ‘Grin’: George Bradley’s no-hitter

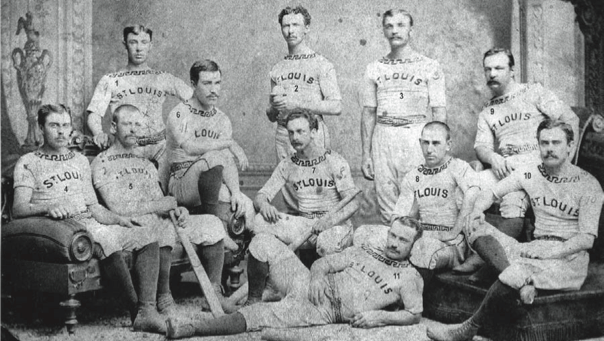

1876 St. Louis Brown Stockings. 1 – Joe Blong, 2 – George Bradley, 3 – Herman Dehlman, 4 – Joe Battin, 5 – John Clapp, 6 – Tim McGinley, 7 – Lipman Pike, 8 – Mike McGeary, 9 – Dickey Pearce, 10 – Denny Mack, 11 – Ned Cuthbert. (NATIONAL BASEBALL HALL OF FAME LIBRARY)

Since 1876 marked the US Centennial, it was only fitting that a man given the name of George Washington should play a starring role in that summer’s events.

This George Washington—his surname was Bradley—wasn’t a politician but a baseball pitcher. On July 15, 1876, less than two weeks after the Centennial observance took place in Philadelphia and less than three weeks after George Armstrong Custer met his doom at Little Bighorn, Bradley became the first pitcher in National League history to throw a no-hit game.

Granted, it was a young National League history at that point. Only the previous February, Chicago businessman William A. Hulbert had gathered together a group to form what would become the National League of Professional Base Ball Clubs.

Bradley pitched for the St. Louis Brown Stockings, and he accomplished his pitching feat against the Hartford Dark Blues at Grand Avenue Park in St. Louis. In two previous meetings that week— one of them coming on his 24th birthday—Bradley had already shut out the Hartfords, both times besting the man who was his pitching opponent again on the 15th, Tommy Bond. Described as a perpetually happy fellow, Bradley was rarely called George or George Washington by those who knew him, but more commonly “Grin.” By whatever name, Bradley entered the game in the midst of an amazing streak that would extend to 37 consecutive shutout innings.

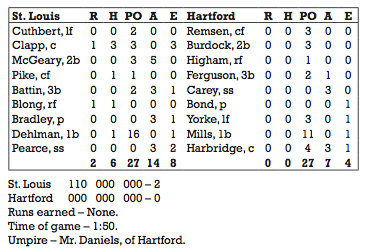

His teammates gave Bradley the only run he would need in the top of the first inning. With one out, catcher John Clapp drove a clean single to center, reached third on a wild throw by Bond, and scored on Mike McGeary’s fly ball.

Bradley’s duties were made more challenging by his teammates’ lack of fielding support. The Brown Stockings committed eight errors that day, the first coming in the opening inning when shortstop Dickey Pearce threw badly to first on a groundball by Jack Burdock. A passed ball sent Burdock to second, but he died at third base.

The Browns added another run in the second. Right fielder Joe Blong’s one-out single got things going, and he took second on left fielder Tom York’s slow fielding. Bradley hit a grounder that should have been played by first baseman Everett Mills, but Mills let the ball slip between his legs, allowing Blong to trot home.

Over the next 7½ innings, Bradley and Bond matched each other goose egg for goose egg, Bradley overcoming sloppy fielding to hold his two-run edge. St. Louis threatened twice. In the third John Clapp doubled to left with one out. He died at second as Mike McGeary popped up to Jack Burdock at second and Lip Pike sent a liner to York in left for the third out. In the sixth Pike beat out a grounder to Burdock at second. He stole second, but got no farther as Joe Battin went down on strikes for the third out.

Going into the eighth inning, the Browns still led 2–0 and Bradley’s consecutive scoreless innings streak had reached 25. Despite the no-hitter being intact, a lapse of control presented Hartford with a golden opportunity to score in its half of the eighth. The frame started out with Tom York reaching first on a base on balls. He was sacrificed to second, and made it to third on a wild pitch. There he remained as catcher Bill Harbridge grounded to McGeary at short, who threw it to Dutch Dehlman at first. Inning over. Threat over. Golden opportunity wasted for the Hartfords.

The St. Louises went quietly in their half of the ninth, leaving Hartford one final opportunity. Jack Remsen grounded to Dickey Pearce at short for the first out, but Battin muffed Burdock’s groundball for the Brown Stockings’ eighth error of the game. Dick Higham was the next man up for the Hartfords and he hit a shot to Battin at third, who caught it and doubled Burdock off first to end the game. Grin Bradley now had his no-hitter and his place in baseball history.

For a while, it looked as though Bradley was going to secure yet another place in baseball history in his next start, three days later against Cincinnati, also at Grand Avenue Park. He was perfect through seven innings and took another no-hitter into the ninth.1 Center fielder Charley “Baby” Jones broke up that opportunity with a double. Jones scored on a hit by catcher Amos Booth, and although the Brown Stockings won 5–1, Bradley’s scoreless innings streak ended at 37. That mark stood until Christy Mathewson tossed 39 straight scoreless innings for the New York Giants in 1901.2

Pitching virtually every game, as was the custom of the time, Bradley won 45 games that season for the Brown Stockings, who finished second in the new league, six games behind the champions from Chicago. His 1.23 earned-run average was the lowest in the league, although the profusion of fielding errors made behind him (and behind all pitchers in those days) gave that statistic less importance than it has today.

Bradley never approached the same performance levels after 1876. Signing with Chicago in 1877, he started 44 games, but won just 18 and saw his ERA climb to 3.31, the highest among pitchers with at least 20 starts. He remained in the big leagues for six more seasons, but usually as a sort of a spare part, winning 75 games but losing 83. After one season with Philadelphia in the American Association, he closed his big-league career pitching for Cincinnati in the 1884 Union Association and worked in the minors until 1890. He became a Philadelphia police officer after his baseball career ended and was retired on a pension when he died in Philadelphia on October 2, 1931.

But if his career as a whole was undistinguished, Bradley certainly distinguished himself by heading a list that is now well into the 200s – the roster of major-league pitchers who have thrown a no-hitter. It was exactly the sort of accomplishment the game might have expected from somebody named George Washington in the summer of ’76.

This essay was originally published in “Inventing Baseball: The 100 Greatest Games of the 19th Century” (2013), edited by Bill Felber. It also appeared in SABR’s “No-Hitters” (2017), edited by Bill Nowlin.

Notes

Additional Stats

St. Louis Brown Stockings 2

Hartford Dark Blues 0

Grand Avenue Park

St. Louis, MO

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.