July 16, 1866: Lipman Pike’s home run record

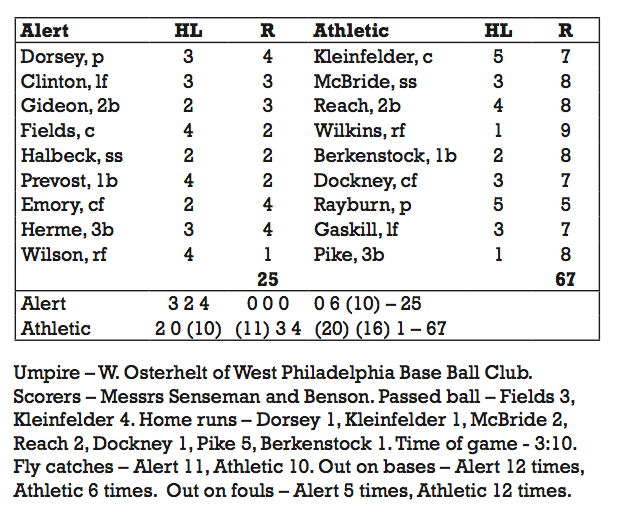

On July 16, 1866, the Athletics of Philadelphia played a ballgame at 17th and Montgomery against the Alerts of Danville, Pa. On this intensely hot and humid afternoon, Lipman Pike played third base and set a standard for home runs in a single game. Many stories of that game recorded that Pike hit six home runs, but the actual number was five. The source of this mistaken figure was his 1893 obituaries. This account was accepted and perpetuated by latter-day historians, despite the box score and contemporary reports of the game.1

On July 16, 1866, the Athletics of Philadelphia played a ballgame at 17th and Montgomery against the Alerts of Danville, Pa. On this intensely hot and humid afternoon, Lipman Pike played third base and set a standard for home runs in a single game. Many stories of that game recorded that Pike hit six home runs, but the actual number was five. The source of this mistaken figure was his 1893 obituaries. This account was accepted and perpetuated by latter-day historians, despite the box score and contemporary reports of the game.1

What was remarkable about this feat was the nature of the baseball used for the game, the spacious, irregular shape of the playing field, and Pike’s size. The ball Pike struck was not the “dead ball” of later decades, but a livelier ball that was often used for an entire game. After a few innings the ball’s condition was not suitable for power hitting. The playing field had an irregular shape with spacious power alleys that sprawled from 300 to about 400 feet in center field.2 Batting ninth, the 21-year-old left-hander in his first year with the Athletics stood only 5-feet-8 and weighed 158 pounds. Years after his playing days were over, fans still talked about the batting prowess and long-distance slugging of the “Iron Batter.” Another Pike feature that contributed to his notoriety was his Jewish faith.

Pike’s father was a refugee from Holland who settled in New York among the Dutch Jewish merchant families. Born in 1845, the second of five children, Lipman grew up in Brooklyn. Against their father’s wishes, he and his older brother, Boaz, played baseball. By 1865 Lipman was good enough to be invited to play for the renowned champions of the National Association, the Atlantics of Brooklyn. He was 20 years old when he appeared in his first game for the Atlantics. The following year Pike made a career move and joined the Atlantics’ major rival, the Athletics of Philadelphia, who lured him by paying him $20 a week.3 The year before he signed with the Athletics, the club leased a new playing ground from the city and outfitted it. Located between 15th and 17th and Montgomery and Columbia Avenues, this irregularly shaped field was the Athletics’ home site until 1871. The grounds were formerly a bivouac and staging area for the Union Army. Here soldiers and workmen for a natural history museum, the Wagner Free Institute, played pick-up ball games. The first regular sanctioned game was played on May 12, 1865.4

Pike’s first season with the Athletics (1866) was marked by historic contests with the Atlantics of Brooklyn. Record crowds attended each game. The first game drew over 30,000 spectators, and the crowds were so dense that it had to be called after one inning. Between the next two Atlantic contests Pike and the Athletics played the Alerts. In this contest Pike used his remarkable speed to beat out long hits that soared to gaps in the spacious center field, a distance of about 400 feet. His other home runs were lofted over 290 feet, clearing a seven-foot-high fence bordering Columbia Avenue in right field. In all the Athletics stroked 12 home runs and won the game 67–25.5

Not much attention was given to Pike’s great game. There were no bold headlines or commentaries about his feat. It was reported merely as another victory for the Athletics. The Athletics finished their National Association schedule with a 23–2 record. But Pike’s tenure in Philadelphia was tenuous. Questions were raised about the loyalty and reliability of paid professional ballplayers.6 As a result, he and other professionals were purged from the team. In 1867 Pike found himself playing for Association teams in New Jersey and New York.

By the time he ceased full-time play a dozen years later, Pike had won four home run titles and set the professional National Association career record for home runs. He was also fourth in RBIs. Despite all of that, Lipman Pike would always be known for what he accomplished in his first full year as a professional ballplayer on the sweltering afternoon of July 16, 1866.

This essay was originally published in “Inventing Baseball: The 100 Greatest Games of the 19th Century” (2013), edited by Bill Felber. Download the SABR e-book by clicking here.

Notes

1 New York Clipper, July 28, 1866; Sunday Mercury, July 22, 1866. The six home run story originated in obituary columns. Sporting Life, October 21, 1893, and The Sporting News, November 11, 1893.

2 See J. Casway, “At the Old Ball Game,” Temple Review, Spring 1992, pp. 21-3. Also see images in Baseball Hall of Fame of Athletics-Atlantics, October 22, 1866, No. 63; Harper’s Weekly, November 18, 1865.

3 Sporting Life, October 21, 1893; New York Clipper, July 9, 1881, August 25, 1866; Sunday Item, October 22, 1893; The Sporting News, November 11, 1893.

4 Unpublished biographical article on Lipman Pike that will appear in J. Casway, Culture and Ethnicity of Nineteenth-Century Baseball, “Before Hank Greenberg There Was Lipman Pike,” p. 3.

5 New York Clipper, July 28, 1866; Sunday Mercury, July, 22, 1866.

6 Ryczek, W. When Johnny Came Sliding Home (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland Publishing, 1998), pp. 107-8; Chadwick Scrapbooks, 1866; Sunday Mercury, May 27, 1866, November 11, 1866; January 22, 1871; New York Clipper, August 25, 1866.

Additional Stats

Athletics of Philadelphia 67

Alerts of Danville 25

Athletic Grounds

Philadelphia, PA

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.