July 17, 1894: Beaneaters stall and feign and pray for rain

Unlike most other sports, baseball has no clock, so a team never has to “beat the clock” as well as an opponent. There are very few times when actual minutes are measured instead of outs in baseball. When a relief pitcher is not yet ready to come into a game, a manager will come out to the mound to stall for time to give him more throws in the bullpen. Or in a rarer instance, if a team is trailing big early in the game and rain is in the forecast, it may stall in any way it can in the hope that the rain will start and the game be called off. This was the case on July 17, 1894, when Boston visited Philadelphia in a strange game that led to a riot on the streets of Philadelphia.

Unlike most other sports, baseball has no clock, so a team never has to “beat the clock” as well as an opponent. There are very few times when actual minutes are measured instead of outs in baseball. When a relief pitcher is not yet ready to come into a game, a manager will come out to the mound to stall for time to give him more throws in the bullpen. Or in a rarer instance, if a team is trailing big early in the game and rain is in the forecast, it may stall in any way it can in the hope that the rain will start and the game be called off. This was the case on July 17, 1894, when Boston visited Philadelphia in a strange game that led to a riot on the streets of Philadelphia.

Boston, winner of the pennant the previous three seasons, was in a tie for first with Baltimore. Philadelphia was in fifth, 7½ games behind. Harry Staley took the mound for Boston while Philadelphia counted on the right arm of Jack Taylor. Boston manager Frank Selee was absent for reasons unknown today, so captain Billy Nash was in charge. Dan Campbell, a Philadelphia native, was umpiring his first National League game.1

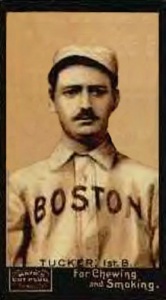

Philadelphia batted first and took an early lead. Sliding Billy Hamilton walked and stole second. Boston players Tommy Tucker, Bobby Lowe, and Nash “raised a big howl”2 to Campbell over the call. Campbell warned them, fined Lowe and Tucker, and threatened to eject Tucker. Tucker, however, “kept up a tirade of abusive language, which aroused the ire of the seven thousand spectators.”3 Hamilton scored on Ed Delahanty’s fly ball.

The score was 1-0 into the fourth, when Boston tied the score. Herman Long singled. Hugh Duffy flied out, but Tommy McCarthy reached on a single, with Long moving to third. Long scored on a double steal.

The game remained tied into the seventh. Boston’s Nash singled, stole second, and went to third on a muffed third strike. Staley popped out, but Lowe singled, and Boston led 2-1. What was a close, exciting contest descended into disarray from this point forward.

In the top of the eighth, Hamilton tripled to left center. Bill Hallman walked and stole second. Delahanty grounded to Tucker, well off the base at first. Tucker fielded, but neither Lowe nor Staley covered first, giving Delahanty the base as Hamilton scored the tying run. Delahanty stole second and scored with Hallman on a single by Sam Thompson. Philadelphia now led 4-2. Lave Cross walked and Jack Boyle beat out a bunt single to load the bases. Joe Sullivan hit a towering drive to left field. McCarthy, in an attempt to decoy the runners, stood dead still as if ready to catch it. The plan didn’t work as the bases cleared when the ball sailed over his head and Sullivan was now at third. Sullivan came home with another run on a groundout, and Philadelphia led 8-2.

“Then the circus proper began,” the Boston Globe wrote.4 Boston players knew their only real chance was for the “ominous sounds of thunder in the heavens”5 to bring rain. In that case the game would end with the final score reverting back to the previous inning, and Boston would win, 2-1. Taylor hit a pop fly to left that McCarthy, Long, and Nash let drop. Taylor wound up on second, and tried to get himself put out by literally walking to third and then home. Boston players just watched him go. Hamilton then grounded between third and short with a true seeing-eye single, as Long and Nash both watched it go by. Hamilton made second, walking the entire way. He scored when Nash got out of the way of Hallman’s hit. Hallman turned it into a walking inside-the-park home run.

Philadelphia tried to find other ways to get themselves out. Delahanty was called out on a foul strike when he stepped out of the batter’s box. Boston players gathered around Campbell to argue. Thompson grounded to first, just past Tucker, who dodged the ball. Cross singled and Thompson was called out for cutting across the infield, missing second base. Nash and Boston players complained that Thompson should have been safe. Nash was, in the words of the Philadelphia Inquirer, “acting like a crazy man, jumping around and abusing the umpire, the spectators and the Philadelphia players and management, while Nash and Lowe were laying down the Boston law of ‘how to play dirty ball’ to the umpire.”6

“Probably 20 minutes were frittered away in this fashion,” the Globe reported, “during which the enraged spectators manifested their displeasure by groans and hisses.”7 Boston players left the field and refused to take their turn at bat. Campbell eyed his watch and, after allowing 30 seconds8 for Boston to get to the plate, had seen enough and called the game to the Phillies.

“Then followed a scene as was never before witnessed on a ball field in this city,” wrote the Globe.9 Angry fans swarmed the field. Tucker had forgotten his glove at first base and went back to retrieve it. Fans circled him and he was given “the shoulder” by someone. “This was the spark that kindled the fire,” in the words of the Globe.10 Someone punched Tucker on the left cheek. Only the crowd kept him standing. The police broke through the mob and with the help of Philadelphia players, including Boyle and Mike Grady “fighting like Trojans,”11 they literally tossed Tucker over the crowd and under the pavilion, where the door to the Boston dressing room was. In front of the door was Sergeant Eglof “and his 250 pounds avoirdupois was a bulwark not easily overcome,” wrote the Inquirer, “and while he kept the mob at bay the doors were closed.”12

The crowd, 1,500 by the Globe’s estimate, was so thick that omnibuses and trolley cars on Broad Street were stopped. In the dressing room, the Phillies owner, Colonel John I. Rogers, and Nash had an “exciting colloquy” in the dressing room. Rogers promised that the National League would take action against the Boston players, while Nash blamed the Phillies.13

Lieutenant Wolf and reserve police officers arrived from the 22nd Precinct to get the players out of the park. The police formed a double line for the team to get to the coach at 15th and Huntington. The team got aboard and rode down Broad Street, with two policemen each on the front and back. Fans hurled rocks at the coach. An officer named Welker jumped off the coach to detain a 14-year-old brick thrower. Walker dragged him into a nearby store and “smacked the lad in the face, and he in turn was given a lively hustling by the crowd, during which the little offender made his escape.”14 The coach driver, seeing the distracted crowd, rumbled off.

The police arrested William Leonard and Lewis Sailor for the Tucker assault, but they were discharged for lack of evidence.15 “The riotous scenes which ensued were traceable entirely to the ruffianly conduct of the visiting players,” the Inquirer wrote. Selee telegraphed National League President Nick Young, blaming the incident on Philadelphia and requesting that the game not count in the standings.16 Young took no action.

The Boston Journal thought there would be consequences felt in the game for years to come. “The National Pastime, a game which the American youth hardly out of his swaddling clothes is taught to play – has received a smirch which will take years to efface. … Upon those who a patronage is worth cultivating – those, whose presence at a ball game lends it both dignity and popularity, the effect will be demoralizing.”17 The Times of Philadelphia, placed blame on the National League since “in all the cases of rowdyism and disgraceful conduct that has transpired on the diamond during the year not a single word has gone forth from headquarters bent on putting an end to it.”18

Tucker was involved in yet another incident at the team hotel after the next day’s game. Players were standing in front of the Hotel Hanover when a man reached over the railing of a passing trolley car and punched Tucker in the mouth. Tucker and Jimmy Bannon chased the trolley and told a police officer to arrest his assailant. Instead, Tucker was ordered back to the hotel. He refused, became hostile to the officer, and spent the night in jail. He was released just in time to get on the train back to Boston.

“I don’t know why it is that the people of Philadelphia pick on me the way they do,” Tucker said.19

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted Baseball-Reference.com, Retoroshet.org, and Felber, Bill. A Game of Brawl: The Orioles, the Beaneaters & the Battle for the 1897 Pennant. (Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 2007), 19-20.

Notes

1 Campbell was installed by chief of umpires Harry Wright to replace Billy Stage after Stage was hit in the head by a foul ball and would later resign; “Tom Tucker Assaulted,” Washington Evening Star, July 18, 1894: 11; Peter Morris, “Billy Stage,” SABR BioProject sabr.org/bioproj/person/6c4a9372.

2 “Disgraceful Riot on the Ball Field,” Philadelphia Inquirer, July 18, 1894: 1.

3 Ibid.

4 “Ends in Fight,” Boston Globe, July 18, 1894: 2.

5 “Disgraceful Riot.”

6 “Disgraceful Riot.”

7 “Ends in Fight.”

8 “Ball Players Face a Riot,” Philadelphia Times, July 18, 1894: 1.

9 “Ends in Fight.”

10 Ibid.

11 “Ball Players Face a Riot.”

12 Ibid.

13 “Disgraceful Riot,” 3.

14 Ibid.

15 “A Smirch. Riot on the Base Ball Field at Philadelphia,” Boston Journal, July 18, 1894.

16 “Both Were to Blame,” Boston Journal, July 18, 1894: 8.

17 “A Smirch.”

18 “Base Ball Comment,” Philadelphia Times, July 22, 1894: 22.

19 “Tucker Meets His Waterloo,” Philadelphia Times, July 19, 1894: 1; “Tommy Tucker Locked Up,” Philadelphia Inquirer, July 19, 1894: 3.

Additional Stats

Philadelphia Phillies 11

Boston Beaneaters 2

Huntington Grounds

Philadelphia, PA

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.