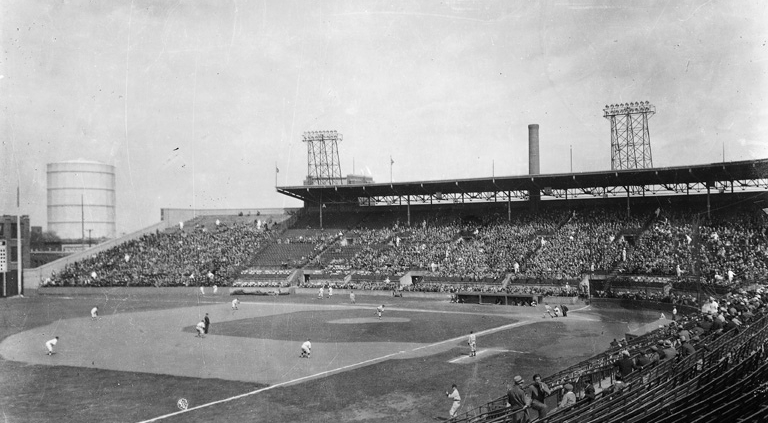

July 18, 1933: Night baseball makes its debut in Montreal

When it opened in 1928, Montreal’s De Lorimier Stadium was considered the preeminent ballpark of the minor leagues. Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis said it was even better than some big-league facilities.1 The luxurious ballpark was also heavily mortgaged, which was a relatively minor concern initially. Everything changed when the stock market crashed in October 1929. As the Depression marched on, the Montreal Royals, like most minor-league teams, were struggling to survive. By the end of 1932, the Royals were teetering on the brink of financial collapse.2

The Montreal club underwent a major financial reorganization in April of 1933 in order to bring in much-needed capital. Two of the new investors, Charles-Émile Trudeau and Roméo Gauvreau, were named vice presidents of Montreal Baseball Club, Inc.3 The cash injection immediately stabilized the team’s financial outlook.4

Despite the team’s winning record in each of the previous three seasons, attendance was still almost 15 percent lower in 1932 than in 1929. The Royals’ shrewd general manager, Frank Shaughnessy, had some ideas to address the dwindling attendance. He sold the International League owners on the Shaughnessy Plan, a proposal to add playoffs for the 1933 season.5 Under the initial version of the system, the league was split into two four-team divisions with the top two teams in each group qualifying for the postseason. The goal was to prevent fan interest from dropping off late in the season by keeping more teams in contention for the league title. The extra games for the four playoff teams were icing on the cake.

Shaughnessy also set out to attract more fans during the week by introducing night baseball to Montreal.6 The concept wasn’t exactly new, considering that the first night game in Organized Baseball was played on April 28, 1930, in Independence, Kansas. Two months later, the International League’s first night game was played in Buffalo.7 By the end of the 1930 season, 38 minor-league teams were playing games under the lights.8

Montreal’s inaugural night baseball game was set for Tuesday, July 18, 1933.9 A local newspaper noted that it was “the first night baseball game in the Dominion,” a claim that didn’t hold up to much scrutiny.10 Montreal was more than two years late to earn that honor. On July 3, 1931, the first night game in Canada had been played at Athletic Park in Vancouver between amateur teams in the Vancouver Senior League.11

The Royals installed a state-of-the-art lighting system at De Lorimier Stadium. Four light standards, each holding 18 1,500-watt bulbs, were installed on the roof of the grandstand. Ninety-foot steel towers with another 24 bulbs each were placed just in front of the wall in both left-center and right-center fields.12

Several fielding errors caused by poor lighting had marred the first International League night game in Buffalo three years earlier, so Shaughnessy set out to avoid similar problems.13 Electricians worked until dawn on game day to ensure that the lights were properly focused. Shaughnessy was at the ballpark throughout the night, checking for shadows on the field.14 He even hit some fly balls to reporters to test out the lights.

The game’s start time was set for 9:15 P.M., almost 40 minutes after sunset, so the lights would have their maximum effect. Excited fans arrived early to survey the historic scene. Aside from a shadowy area in deep center field, the playing surface was generally considered to be well lit. The Montreal Gazette breathlessly described the light towers in the outfield as “giant, gleaming diamond stick-pins.”15

The Royals came into the game with a 47-51 record, eight games behind second-place Toronto in the Northern Division. Their opponents, the Albany Senators, sat in third place in the Southern Division with a 45-54 mark. The 13,000 fans in attendance — nearly three times as many as had shown up to see the same two clubs play the previous afternoon — were treated to an entertaining ballgame.

Montreal left fielder Lou Finney tripled in the bottom of the first inning, and he continued home when Harold King’s relay from the outfield was thrown wildly into third base. The Royals increased the lead to 2-0 in the bottom of the fourth on a fly ball by Red Sox farmhand Urbane Pickering.

Albany got on the scoreboard in the top of the fifth, getting an unearned run on a fly ball by catcher Tom Padden. RBI singles by Jimmy Ripple and Bennie Tate extended the Royals’ lead to 4-1 in the bottom of the fifth.

Montreal starter Tim McKeithan had given up only one hit through the first five innings before running into serious trouble in the sixth. Albany scored two quick runs on three singles and a double to close the score to 4-3. With only one out and a pair of runners on base, Royals player-manager Oscar Roettger yanked McKeithan in favor of his ace reliever, 34-year-old Clarence Fisher. “The Kingfish” gave his team a boost by retiring the side and preventing any further damage.16

Some sloppy fielding by the Senators led to a pair of unearned runs in the bottom of the sixth inning, making the score 6-3 for the Royals. The game tightened up once again when 23-year-old Stan Hack launched a two-run home run off Fisher in the top of the eighth. The veteran Montreal hurler was victimized for the long ball again an inning later when right fielder Tommy Thompson tied the game, 6-6, with a dramatic solo home run.

Albany southpaw Jimmy Carithers returned to the mound in the bottom of the ninth for his second inning of work.17 After Roettger opened the frame with a double, Carithers issued an intentional walk to pinch-hitter Ivey “Chick” Shiver. Tate, who came into the game with a .322 batting average, bunted the ball down the third-base line for a single that loaded the bases with nobody out. With the clock nearing midnight, pinch-hitter Bill Regan hit a long fly to left-center field that was easily deep enough to score Roettger from third. Center fielder Mike Kreevich got back in time to make the catch, but he dropped the ball for the fifth Senators error of the game, and Roettger trotted home with the winning run. Although six errors were committed in the game, only Kreevich’s misplay could be blamed on the lighting.18

The two teams played another night game on August 15 during the Senators’ next visit to Montreal. The Royals had been treading water since the middle of July, yet they found themselves only 2½ games out of a playoff spot coming into the game thanks to the slumping Toronto Maple Leafs. Without the Shaughnessy Plan in place, Montreal would have been a whopping 16½ games out of first place. A sizable Tuesday-night crowd of 7,000 fans watched the Royals get thumped 10-1, with the home side’s sole run coming on Finney’s homer.19 It was his last game in a Montreal uniform. With Connie Mack’s team in need of reinforcements, Finney was recalled by the Philadelphia Athletics, which left a big hole in the Royals lineup.20 Their playoff chances took an even bigger hit when Tate, the team’s leading hitter, broke his finger in an August 19 game and missed the rest of the season.

Even with these setbacks, Montreal remained in the playoff race until the final weekend of the season. The Royals won 12 of their last 17 games and finished with an 81-84 record, a mere half-game behind second-place Buffalo.

In the 1933 version of Shaughnessy’s playoff system, the two first-place teams squared off against each other in the first round, as did the two second-place squads. When Buffalo, with an 83-85 regular-season record, went on to win the International League championship, the Shaughnessy Plan became the subject of much derision. Shaughnessy held firm. “The best defense of the play-offs,” he said, “will be found in the receipts during the month of August and early September among the contending clubs.”21 Sure enough, Buffalo and Montreal — two sub-.500 teams — led the International League in attendance that season.22

To address the criticism, a second version of the Shaughnessy Plan was adopted for the 1934 season. The two divisions were scrapped, and the standings reverted to the usual eight-team setup. One first-round playoff series featured the first- and third-place teams, while the other had the second- and fourth-place clubs facing off.23 The postseason concept began to take root. By 1939, the Shaughnessy Plan was used by nearly every minor league.

After hitting rock bottom in 1933, when only 14 leagues were in operation, the minor leagues rebounded to a robust 44 circuits by 1940.24 The introduction of night baseball, along with the addition of playoffs, had helped the leagues weather the financial storm until economic conditions improved. Shaughnessy, having been involved in both of these innovations, became one of the most respected men in minor-league baseball. He took over as president of the International League in October 1936, a post he held until his retirement in 1960.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Baseball-Reference.com and the SABR/Baseball Reference Encyclopedia. The box score from this game is available on page 12 of the July 19, 1933, edition of the Montreal Gazette.

Photo: Musée McCord Museum

Notes

1 William Brown, Baseball’s Fabulous Montreal Royals, (Westmount, Quebec: Robert Davies Publishing, 1996), 26. The name “De Lorimier Stadium” is used instead of “Delorimier Stadium” to reflect the correct French name (Stade De Lorimier).

2 Brown, 34.

3 Charles-Émile Trudeau’s teenage son, Pierre, went on to serve as Canada’s prime minister from 1968 until 1979 and 1980 until 1984. Pierre’s son, Justin, was elected prime minister in 2015.

4 Brown, Baseball’s Fabulous Montreal Royals, 35.

5 Charlie Bevis, “Frank ‘Shag’ Shaughnessy,” SABR BioProject, sabr.org/bioproj/person/022eb7f7, accessed May 22, 2020.

6 Brown, 35.

7 The International League’s first night game was played on July 3, 1930, at Offermann Stadium in Buffalo between the Bisons and the Montreal Royals.

8 Mark Metcalf, “Organized Baseball’s Night Birth,” Baseball Research Journal, Fall 2016, sabr.org/research/organized-baseball-s-night-birth, accessed May 22, 2020.

9 The other Canadian team in the International League, the Toronto Maple Leafs, did not begin playing night games at home until 1934.

10 “Stadium Ready for Night Ball,” Montreal Gazette, July 18, 1933: 12.

11 Andy Lytle, “Night Baseball Is Well Received by Vancouver Fandom,” Vancouver Sun, July 4, 1931: 12.

12 “Royals Triumph in Local Night Ball Inaugural,” Montreal Gazette, July 19, 1933: 12.

13 Brown, 36.

14 “Stadium Ready for Night Ball.”

15 “Royals Triumph in Local Night Ball Inaugural.”

16 “Royals Triumph in Local Night Ball Inaugural.”

17 The reliever’s full name is James A. Carithers. Although Baseball Reference lists Carithers as having pitched for Albany in 1934 and 1935, there was no mention of him pitching there in 1933 as of May 25, 2020. However, Carithers pitched for Albany in two games in Montreal on July 18-19, 1933. The statistics on page 8 of the January 18, 1934, edition of The Sporting News show that he went 2-2 in nine appearances for Albany in 1933.

18 Five of the six errors were committed by Albany. Urbane Pickering made the only Montreal error.

19 “Royals Routed by Albany, 10-1, in Night Game,” Montreal Gazette, August 16, 1933: 12.

20 The 1933 Montreal Royals roster included players on option from the Philadelphia Athletics (e.g. Lou Finney and Tim McKeithan), Boston Red Sox (e.g. John Michaels, Tom “Jack” Winsett, and Urbane Pickering), and Detroit Tigers (e.g. Ivey Shiver). Some players, such as Bennie Tate, were directly under contract with Montreal. Using optioned players made sense from a financial standpoint, since they remained on the major-league team’s payroll while playing for Montreal. However, they could be recalled by their parent club at any time.

21 Bevis.

22 Buffalo led the league with attendance of 245,082. Montreal was second with 179,396 fans despite finishing in last place in the Northern Division.

23 A third version of the Shaughnessy Plan was adopted by the International League in 1939. The first-place team played the fourth-ranked squad in one first-round series, while the clubs with the second and third-best records played in the other.

24 Lloyd Johnson and Miles Wolff, eds., The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, (Durham, North Carolina: Baseball America, 1997), 263. Close to 30 minor leagues had begun play each season throughout the 1920s. The minor leagues of this era played in five classifications, AA (the equivalent of today’s Triple A) through D.

Additional Stats

Montreal Royals 7

Albany Senators 6

De Lorimier Stadium

Montreal, QC

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.