July 2, 1963: Marichal outduels Spahn in 16-inning thriller

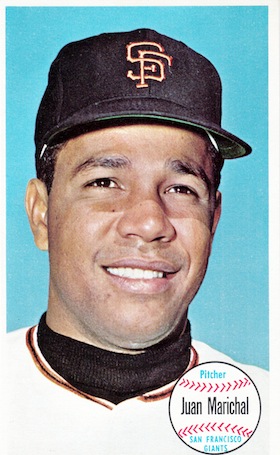

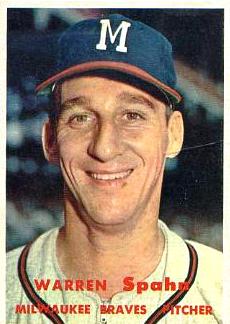

As the 1963 National League season moved into its fourth month, the Milwaukee Braves visited San Francisco for the second time. On July 2 San Francisco sent 25-year-old Juan Marichal out against Warren Spahn, 17 years his senior, in the Tuesday night opener of a three-game set.

As the 1963 National League season moved into its fourth month, the Milwaukee Braves visited San Francisco for the second time. On July 2 San Francisco sent 25-year-old Juan Marichal out against Warren Spahn, 17 years his senior, in the Tuesday night opener of a three-game set.

The Giants starter was looking to avenge a 3-1 loss on April 28 to the antediluvian left-hander, by then pitching in his 19th major-league campaign. The third-place Giants (44-34) were 1½ games behind the first-place St. Louis Cardinals, while the 38-38 Braves were sixth, 6½ games out of first. Marichal had won 12 games in 15 decisions for his team, and Spahn was sporting an 11-3 record.

At slightly past 8 o’clock, Marichal took the Candlestick Park mound. More than 4 hours and 15 innings later, he was still toiling there. And so was Warren Spahn – in a scoreless pitching duel.

The Braves had mounted a serious scoring threat in the top of the fourth inning. Marichal disposed of the first two batters before trouble arose. The right-hander walked Norm Larker, and Mack “The Knife” Jones followed with a single to left, moving Larker to second. Del Crandall hit a soft single to center that Willie Mays fielded, then lasered to the plate to nail Larker trying to score. It had been a charmed half-inning for the Dominican pitcher. Henry Aaron led off the frame with a drive to deep left field that Marichal later said he thought was gone.1 Willie McCovey hauled the ball in a few feet from the fence, as Candlestick Point’s strong westerly winds knocked it down.

McCovey nearly ended the game in the bottom of the ninth. The Giants left fielder smoked a pitch deep to right field, just missing a home run – or so said the first-base umpire. Local beat writer Curly Grieve expanded: “McCovey was so enraged when Chris Pelekoudas called the blast a foul that momentarily it appeared he would push the arbiter around the outfield and wind up ejected in the clubhouse. McCovey, [manager] Alvin Dark and [first-base coach] Larry Jansen surrounded Pelekoudas, claiming the ball left Candlestick fair. Pelekoudas stuck to his call, which took courage.”2

“I followed the ball all the way out but evidently the umpire didn’t. As hard as I hit the ball it didn’t have a chance to curve before leaving the ballpark,” McCovey said after the game.3 When he stepped back into the batter’s box, a miffed McCovey grounded out to first base, with Spahn covering. After a two-out single by Felipe Alou, Orlando Cepeda popped up to third base, and the scoreless game moved into extra innings.

With two outs in the top of the 13th, Braves second baseman Frank Bolling singled off Marichal, ending a string of 16 batters in a row retired by the Giants’ workhorse since a walk to Aaron in the eighth. Bolling was left stranded by the next hitter, Aaron, who popped up to first baseman Cepeda in foul ground.

Marichal was scheduled to bat third that inning. Cepeda later recalled the moment in a 1998 memoir. Alvin Dark asked Marichal if he had had enough. Cepeda remembered Marichal barking at Dark, “A 42-year-old man [Spahn] is still pitching. I can’t come out!”4 Dark accepted – or was startled into acceptance by Marichal’s ardor – and let him bat. Marichal flied out to complete the inning, and the game pushed forward.

The Giants made a strong bid to get Marichal a win in the bottom of the 14th. With two outs, they loaded the bases on a double, a walk, and an error by Denis Menke, in at third base for Eddie Mathews, who was removed after two at-bats due to a sore right wrist. Spahn then coolly retired Giants catcher Ed Bailey on a fly to center, ending the inning and extending the deadlock.

Marichal shook off his catcher’s failure and assailed the mound for the 15th time. As if he had gained strength against his team’s impotency, the fourth-year pitcher resolutely retired the side in order, his counterpart the second out on a foul popup. Spahn duplicated the orderly effort and set down the three hitters he faced in the bottom half of the frame, Marichal the third out on a strikeout.

Marichal and Spahn had recorded 90 outs, equally divided through 15 innings of pitching grandeur. Had it been a championship prizefight, a draw could have been called to no one’s contention. Had they been two enslaved gladiators, the reigning Caesar would have been compelled to free both of them. Such magnificence from the hill had rarely been displayed in baseball annals by two pitchers in the same game.5

Marichal and Spahn had recorded 90 outs, equally divided through 15 innings of pitching grandeur. Had it been a championship prizefight, a draw could have been called to no one’s contention. Had they been two enslaved gladiators, the reigning Caesar would have been compelled to free both of them. Such magnificence from the hill had rarely been displayed in baseball annals by two pitchers in the same game.5

As was his custom and as he had done in each of the prior 15 innings, Juan Marichal sprinted to the mound in the top of the 16th with all the appearance of a schoolboy released from classes for the summer, except that he clutched a baseball glove instead of a glowing report card. Inning after inning after inning, Juan Antonio Marichal had scaled the hilly sandbox that acted as his playground and disposed of batters with a brimming confidence that bordered on nonchalance. How much longer could the bravado of youth sustain him?

Marichal set down the first two batters of the 16th on fly outs to right field and center field respectively. He gave up a two-out hit to Menke, the eighth and final hit he allowed in the game and only the second by the Braves since the seventh inning. Marichal then registered, on a comebacker, his 48th out, on his 227th pitch of what was now, according to the scoreboard clock, a new day.

As was his custom and as he had done in each of the prior 15 innings, Warren Spahn strolled to the mound in the bottom of the 16th with all the appearance and enthusiasm of a factory worker walking to his next shift, except that he toted a baseball glove instead of a lunch pail. Inning after inning after inning, Warren Edward Spahn had reached his elevated, dirt-compressed workstation and methodically doled out reject-tags to an assembly line of hitters. How much longer before the albatross of advanced age claimed him?

Braves outfielder Don Dillard nestled under a fly ball hit by leadoff batter Harvey Kuenn, and with the catch Spahn recorded the first out of the bottom of the 16th inning. The shrewd southpaw prepared to pitch to the next armed challenger, Willie Mays. The cruelty of baseball for a starting pitcher is that one bad pitch can often ruin the cumulative effort of 100 good ones. In Spahn’s case, at a few minutes past midnight, it was 200 good ones. The same ball Kuenn had swung under and lifted to Dillard in center field, Spahn threw as his 201st pitch to Mays.

Mays’ bat met Spahn’s first pitch with a crackling fury that sent the ball shooting high and far into the heavy San Francisco night, soaring on a shimmering arc of triumph not even the treacherous Candlestick Park winds could betray. And just like that, the dramatically pitched game dramatically ended – Marichal the exhausted victor, Spahn, the valiantly defeated.6

Only once, in the six decades since, has one pitcher thrown as many innings in one major-league game as Marichal did that night against Spahn.7

Over the 16 innings, Marichal allowed the eight hits along with four walks, and struck out 10. Spahn yielded nine hits and walked one (intentionally, Mays), with only two strikeouts.

Both stalwarts, who were pitching on three days’ rest, made their next appointed starts with no ill aftereffects (the Sunday before the All-Star Game). Spahn complained of a sore elbow, which apparently flared up on him enough to land him twice on the disabled list. He still went on to lead the league in complete games with 22 at season’s end, while garnering his 13th and final 20-win campaign with a mark of 23-7.

Three days into September, Marichal became a 20-game winner for the first time. In all, he started 40 games for the Giants and finished the season with a sterling 25-8 record and 18 complete games.

After the game, Spahn’s teammates greeted their aged warrior – the last player to enter the clubhouse because of an interview session – with their own tribute. Quoting Spahn’s fellow starting pitcher Bob Sadowski, writer Jim Kaplan described it: “When Spahn arrived, everyone stood, applauded, and lined up to shake his hand. ‘If you didn’t have tears in your eyes, you weren’t nothing.’”8

The game would not be complete without returning to that baseball savant known as Willie Mays. In the fourth inning of this contest, Mays threw a runner out at the plate from center field, which allowed this game for the pitching ages to develop, then won the game in the 16th inning with a home run.

This was Willie Mays, every day.

SOURCES

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Baseball-Reference.com, Retrosheet.org, the San Francisco Examiner, and the Milwaukee Journal.

Keri, Jonah. “The Greatest Pitching Duel in Human History,” Grantland.com, July 9, 2013. https://grantland.com/the-triangle/the-greatest-pitching-duel-in-human-history. Accessed on May 26, 2022.

https://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/SFN/SFN196307020.shtml

https://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/2004/B06250BOS2004.htm

NOTES

1 Curly Grieve, “Juan, Spahn, All Agree: ‘Twas Terrific Game,’” San Francisco Examiner, July 4, 1963.

2 Grieve.

3 Grieve.

4 Orlando Cepeda and Herb Fagen, Baby Bull: From Hardball to Hard Time and Back (Dallas: Taylor Publishing Company, 1998), 93.

5 On August 13, 1954, Jack Harshman of the Chicago White Sox defeated Al Aber of the Detroit Tigers, 1-0, in 16 innings at Comiskey Park. Both pitchers went the distance. Harvey Kuenn was the Tigers’ shortstop. Nine years later, Kuenn was the Giants’ third baseman behind Marichal. The infielder played the entire way in both marathons. Two seasons after the Marichal-Spahn classic, the Phillies’ Chris Short and the Mets’ Rob Gardner locked up in a scoreless duel for 15 innings on October 2, 1965, at Shea Stadium. Both pitchers retired after the 15th, and the game (the second of a doubleheader) ended in a 0-0 tie after 18 innings, halted by curfew.

6 Bob Wolf, “Spahn Loses Shutout on Homer by Mays,” Milwaukee Journal, July 3, 1963. Mays’ blast was his 15th of the season and 353rd of his storied career. Spahn had accumulated a scoreless string of 27 1/3 innings before Mays ruined it, and had thrown 31 2/3 innings without walking a batter before intentionally passing Mays in the 14th.

7 On September 1, 1967, Marichal’s moundmate Gaylord Perry, a right-hander, started and pitched 16 scoreless innings in Cincinnati – the last time (as of the 2022 season) that a pitcher has thrown as many innings in a baseball game. Goose eggs galore reigned in that game, which lasted 20 scoreless innings before the Giants pushed across a run in the top of the 21st inning to win, 1-0. “When Gaylord trudged off the diamond after hurling all those 16 memorable innings, the crowd at Crosley Field gave him a standing ovation. Perry acknowledged the ovation by tipping his cap – with his left arm. ‘I couldn’t raise my right,’ he said.” Bob Stevens, “Hat’s Off,” The Sporting News, September 30, 1967: 19. (Five days later, Perry had no trouble with his arm. He pitched a 2-0 shutout in his regularly scheduled start against Houston.)

8 Jim Kaplan, “The Best-Pitched Game in Baseball History: Warren Spahn and Juan Marichal,” The National Pastime, No. 27, 2007.

Additional Stats

San Francisco Giants 1

Milwaukee Braves 0

16 innings

Candlestick Park

San Francisco, CA

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.