July 25, 1918: Senators’ Walter Johnson and Browns’ Allen Sothoron battle for 15 innings

Perhaps no baseball season has ever begun with more uncertainty than the 1918 pennant chase. As the season began, the United States had been at war for a year, during which time major-league players had been largely unaffected by the world’s events. On July 1, 1918, however, the sport’s privileged existence was shattered when Secretary of War Newton Baker ruled that baseball was “non-essential” to the war effort, and mandated that ballplayers either seek war-related jobs or face military draft eligibility. This “work or fight” decree severely threatened the National Pastime’s equilibrium.

Perhaps no baseball season has ever begun with more uncertainty than the 1918 pennant chase. As the season began, the United States had been at war for a year, during which time major-league players had been largely unaffected by the world’s events. On July 1, 1918, however, the sport’s privileged existence was shattered when Secretary of War Newton Baker ruled that baseball was “non-essential” to the war effort, and mandated that ballplayers either seek war-related jobs or face military draft eligibility. This “work or fight” decree severely threatened the National Pastime’s equilibrium.

Of course, baseball’s owners immediately protested Baker’s decision. In turn, Baker, who admitted to little knowledge of baseball’s business or how best to enact the order, agreed to postpone his decree until September 1; he also committed to meet on July 24 with baseball’s representatives to discuss how the work-or-fight order might be implemented. Unsure how the ruling would affect the season, the American League announced that unless it was given some assurances as to what to expect from the War Department, it to cease operations.

Under this cloud, the regular season progressed. One might think that given the vagueness of Baker’s order the players naturally would have become preoccupied with their immediate futures, causing their performances to suffer. Not so for everyone. Case in point: Walter Johnson, one of the sport’s preeminent stars. In the midst of baseball’s maelstrom, the Big Train produced one of the most dominant exhibitions of his legendary career.

On July 25 Johnson’s Washington Senators opened a four-game series against the St. Louis Browns at Sportsman’s Park in the Gateway City. Fresh from a four-game sweep of the Chicago White Sox, the Senators came into the game in third place in the American League, with a 47-41 record. With Senators manager Clark Griffith home in D.C. awaiting the outcome of Secretary Baker’s meeting, George McBride directed the team. Scarcely could McBride imagine how little his managerial instincts would be required on this day.

Across the field, the Browns, too, were skippered by a new manager, although one who’d already been on the job for a month. The Browns’ 88th game of the season was the first home game for Jimmy Burke, the team’s third manager of the season.1 After a seven-year playing career and a 90-game managerial stint in 1905 with the crosstown Cardinals, Burke had spent four seasons the Detroit Tigers coaching staff (1914-1917) before taking the Browns’ helm on June 28, 1918, in the team’s 63rd game. From that date, amazingly, the Browns spent the next 25 games on the road, so this was the first time the home crowd saw the new manager of their sixth-place squad. As it turned out, Burke and the fans were both in for an agonizing afternoon.

If Walter Johnson was assuredly going to be tough for the Browns to beat, his opponent promised to be no less a challenge for the Senators’ offense. Twenty-five-year-old right-hander Allen Sothoron was that most enigmatic of Deadball Era pitchers, a spitballer. In fact, already this season Sothoron, who came into the game on a personal five-game winning streak, had gotten the best of the Big Train just 18 days earlier, when they squared off in Washington. Sothoron won, 3-0, allowing just three singles. Sothoron had notched wins in both of his previous starts against Washington (with one loss in relief), while Johnson had gone winless in his two starts against the Browns (with one save in relief). With a 10-8 record and 1.97 ERA, Sothoron was the Browns’ ace; so, too, was Johnson (16-10, 1.33) for the Senators. This game, then, had the makings of a classic pitchers’ duel.

The confrontation more than lived up to its potential. For Sothoron, the story of this afternoon was not that he allowed 12 Senators hits, but that in spite of those hits, his “exhibition, while not quite so impressive as Johnson’s, still was really deserving of more credit, for the Senators had numerous scoring opportunities, all of which, until the final stanza, Sothoron succeeded in erasing.”2 For Johnson, the game was marked not simply by a paucity of Browns runners on the basepaths, but by the degree to which he proved “positively invincible”3 in the few instances when the batters did reach base. That each man offered his best was vital to their respective teams, for, as the press related the next day, “It became apparent early in the game that one run by either club would win the contest.”4

One look at the line score suggests how the game’s suspense grew. Over the first three innings, neither team scored; nor were any runs plated in the fourth, fifth, or sixth innings. While over this period Sothoron may have had to quell some of the Senators’ aforementioned “numerous scoring opportunities,”5 Johnson, with just a few exceptions, totally handcuffed the Browns. After the first six St. Louis batters had been retired in order, Earl Smith coaxed a leadoff walk in the third inning, finally giving the Browns a baserunner. Yet, after Smith advanced to second on a sacrifice by the next batter, Les Nunamaker, the inning ended with Smith standing on second base.

The fourth inning presented the Browns with what was their best scoring chance of the game. When it failed, however, Johnson became virtually unhittable. Batting second for the Browns and leading off the bottom of the inning was Jimmy Austin, whom Johnson retired for the first out. Next up was the brilliant George Sisler. As Johnson fired, Sisler swung and lined one down the left-field line; the speedy Sisler stopped at third with a triple. To the plate strode the cleanup hitter, lefty-swinging Ray Demmitt. In this, his sixth major-league season, Demmitt would post a career-best 61 RBIs, and here he “strove mightily to tally Sisler,”6 driving a fly ball to right field. But as Sisler broke for home, Frank “Wildfire” Schulte, 35 years old and in his final season, fired a “beauty bright peg”7 to catcher Eddie Ainsmith, who tagged Sisler for the out. Sisler’s hit had been the Browns’ first of the game. It would be a while before they got another.

For the next seven innings the Browns had no answers for Johnson’s offerings; in each inning, he retired the side in order. Yet Sothoron, too, “clung firmly to the pace set by his illustrious adversary,”8 so the scoreless game moved to the 12th. That inning, St. Louis finally got its second hit, when Nunamaker singled to left field. After Nunamaker advanced to second on Sothoron’s sacrifice, the Browns seemed poised to score, but again Johnson stranded the runner. Both starters moved on to the 13th.

That inning, the Browns mounted their final scoring threat, but again came up empty. With one out, Demmitt blasted a double off the right-field wall. As Demmitt took a long lead off second, however, Ainsmith rifled a throw to shortstop John “Doc” Lavan,9 who tagged him out. The next batter, Jack Tobin, pushed a “fluke”10 bunt safely past Johnson but when he subsequently tried to steal second, he too was retired Ainsmith-to-Lavan. It was the Browns’ last gasp.

Though Sothoron had allowed 10 hits through 14 innings, the Senators had not scored. Their drought ended with two outs in the top of the 15th inning. Following an Eddie Foster single up the middle, Joe Judge came to the plate. As Foster ran with Sothoron’s pitch, Judge hit a long, high fly to right-center field, where it fell for a double. Foster scored standing up, and the Senators led 1-0. Johnson ended the game in the bottom of the inning.

It had been a sensational outing for the Big Train. In 10 of 15 innings he had retired the Browns in order, and from the fifth inning to the 12th not one St. Louis batter had reached first. Remarkably, too, with just four hits and two walks, the Browns had left just two men on base. Known for strikeouts, Johnson fanned only three. With those accomplishments, it was hard to argue with the writer who contended that “when a club gets but four hits in 15 innings and scores not one run during that time, there isn’t much chance for victory.”11Indeed, there wasn’t.

This article appears in “Sportsman’s Park in St. Louis: Home of the Browns and Cardinals at Grand and Dodier” (SABR, 2017), edited by Gregory H. Wolf. Click here to read more articles from this book online.

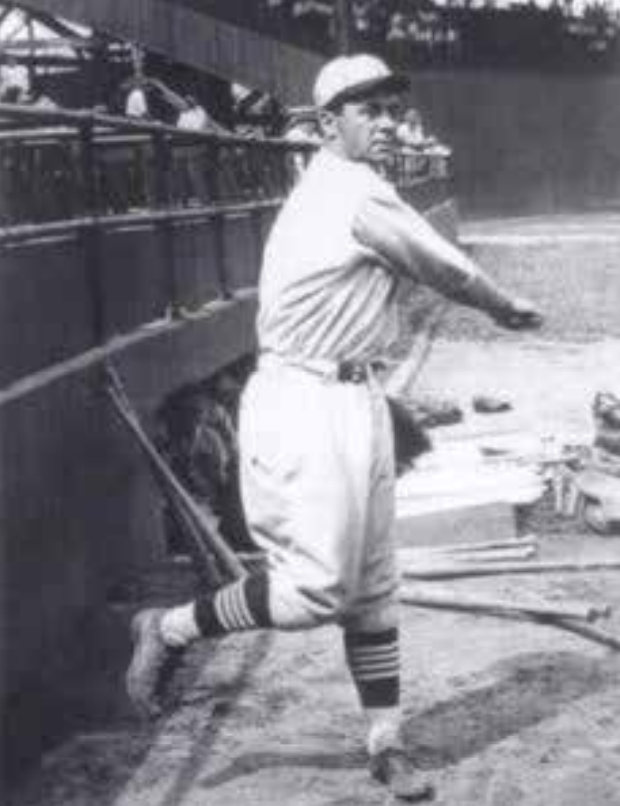

Photo Caption

Coming off an AL-high 19 losses in 1917 (tied with teammate Bob Groom), Allen Sothoron went 12-12 in 1918 with a 1.94 ERA. (Library of Congress)

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted:

thisgreatgame.com/1918-baseball-history.html.

facs.org/about%20acs/archives/pasthighlights/crowderhighlight.

Retrosheet.org.

Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 The first two managers had been Fielder Jones (with a 22-24 record) and Jimmy Austin (7-9).

2 “Johnson Winner Over Sothoron in 15-Inning Combat,” St. Louis Post- Dispatch, July 26, 1918: 16.

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid.

5 For this game summary the author could rely only on game descriptions, none of which provided specifics as to the Senators’ scoring chances in any inning other than the last.

6 St. Louis Post-Dispatch, July 26, 1918: 16.

7 Clarence F. Lloyd, “Sothoron Is Beaten in 15-Round Duel by Famed Fireball King,” St. Louis Star and Times, July 26, 1918: 11.

8 St. Louis Post- Dispatch, July 26, 1918: 16.

9 Lavan had been acquired by the Senators from the Browns on December 15, 1917, but the 1918 season was his only one in Washington. In early September of 1918, Lavan, a naval surgeon, reported to the Great Lakes Naval Training Station, where in addition to his medical duties he also managed the baseball team. Upon his death in 1952, Lavan was buried at Arlington National Cemetery.

10 St. Louis Post- Dispatch, July 26, 1918: 16.

11 Ibid.

Additional Stats

Washington Senators 1

St. Louis Browns 0

15 innings

Sportsman’s Park

St. Louis, MO

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.