July 31, 1921: Atlantic City Bacharach Giants pound the Indianapolis ABCs at Ebbets Field

Sunday games were the big games for Negro League teams, when Black fans of both genders, often coming from church still dressed to the nines, would head for the ballpark for social as much as athletic entertainment. To see the game, of course, each of them had to buy a ticket, making Sunday games financial gold mines for team owners, as well as cultural events.

Sunday games were the big games for Negro League teams, when Black fans of both genders, often coming from church still dressed to the nines, would head for the ballpark for social as much as athletic entertainment. To see the game, of course, each of them had to buy a ticket, making Sunday games financial gold mines for team owners, as well as cultural events.

As the popularity of Black baseball progressed, teams sought out the largest available venues for these games. This included renting the parks of White major-league franchises when those teams were on the road. The Brooklyn Dodgers’ Ebbets Field was among the first major-league parks to host Black games, beginning in 1919 as the home away from home for the Atlantic City Bacharach Giants. Founded by Atlantic City businessmen in 1916, the team by 1921 was owned by two New York City figures: Barron D. Wilkins, a Harlem nightclub owner with a lot of money but no particular grasp of baseball, and John W. Connors, a career sportsman with less money than Wilkins but a wealth of baseball knowledge. He had founded his first team back in 1904. Connors seized on the Dodgers’ ballpark as a New York location for the Bacharachs, and they were soon playing multiple games there each season, usually on Sundays.

The Indianapolis ABCs were a full-fledged member of the Negro National League. The Bacharachs, as were other Eastern clubs, were associate league members. This gave them the opportunity to schedule lucrative games against NNL teams, although not to compete for the pennant. This game was the first of a dozen between the two teams as they barnstormed their way from New York City as far south as Norfolk, Virginia, before swinging back up to Atlantic City.

The Brooklyn Daily Eagle’s game report put attendance at “eight or nine thousand,” while the Chicago Defender, the Black weekly, had it at 10,000, and its New York counterpart, the Age, estimated 15,000.1 Even the lower number would have been a healthy turnout for a Negro League game in the early 1920s. The Eagle’s reporter, edging toward but not adopting the paternalistic tone that Whites often used to describe Black games and crowds, described the stands as “a riot of color,” adding, Every colored lady and gent from the uppermost stretches of Harlem came down to their Brooklyn brethren to cheer on the dusky phenoms.”2

Before the game the fans got an extra treat, a glimpse of former Black heavyweight boxing champion Jack Johnson. Jack was only three weeks out of prison after having been convicted of having transported women across state lines for prostitution, although it’s likely he was targeted for the crime because he was a famous Black man who won titles from White boxers and consorted with White women.3 Johnson likely came to the game as a step in a drive to revive his popularity among Black New Yorkers. But he also was a friend of Barron Wilkins (who had made a lot of money betting on Johnson’s championship win in 1910).4 Jack was introduced before the game but couldn’t stay more than a few innings due to another commitment, a speaking engagement at a church.5

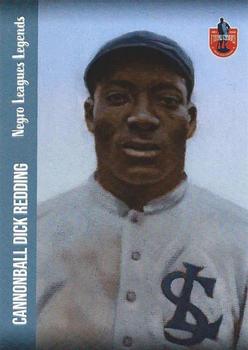

Sunday Negro League games usually featured top pitchers, and this one was no exception. The Bacharachs’ starter was manager Dick “Cannonball” Redding, winner of 16 games that season against Negro League-level competition. Manager C.I. Taylor of the ABCs sent out Dicta Johnson, who wound up the season with 11 wins, the second most for Indianapolis.

Both hurlers were on their games – the score was tied, 2-2, going into the bottom of the sixth inning. The ABCs scored a run in the top of the first on a single by C.I.’s younger brother, first baseman Ben Taylor. The Giants loaded the bases on hits and walks in the bottom of the inning. Then catcher Julio Rojo was “hit on the noodle”6 by an errant Johnson pitch, forcing in a run. Rojo scored again in the fourth on a sacrifice fly, but the ABCs tied the game in the top of the fifth when Johnson hit a leadoff triple and later came home on an error.

But the Bacharachs blew the game open in the bottom of the sixth. Right fielder Elias “Country” Brown led off with a triple, and Rojo and shortstop Dick Lundy followed with singles. Taylor relieved Johnson with Harry Kenyon to try to keep the game in order, but Redding, the second batter he faced, singled. Left fielder George Shively also singled, third baseman Oliver Marcelle doubled, and Atlantic City had four runs. The Giants scored another in the seventh, when Lundy singled in Rojo (who despite being conked on the head in the first, kept getting on base and scored four times in the game). They piled on four more in the bottom of the eighth through a combination of Bacharach hits, including a two-run single by Lundy, and ABCs walks and errors.

Redding, who pitched a complete game, gave up a third run to Indianapolis in the top of the ninth. He was a little off his usual performance, yielding 12 hits and striking out only three. But on the other hand, he issued only a single base on balls. Marcelle and Lundy each had three hits; two of Marcelle’s were doubles, as was one of Lundy’s.

The game was no gem – there were five errors in all. This led the Eagle reporter to pen an exaggerated description of the fielding that nonetheless provides a real hint of the liveliness that often made Black games good watching: “[T]hose present saw a game more chock full of stunt catches and spectacular stops than ordinarily are provided in a half dozen games. They also saw an equal number of muffs and ground errors, which is to be expected when you have 18 men who have no use for their right hand when attempting to catch a fly or stop a grounder. Any one of them would run his head off to get at a ball which he could stab at with one hand and then turn a graceful somersault, whereas anything that came straight at them and had to be taken at a standstill with both hands was looked upon as a boring task.”7

The Giants and ABCs’ day at Ebbets Field was supposed to be a doubleheader, but the rain that threatened throughout the first game finally came down early in the second, and the contest was called after three innings, in which William “Dizzy” Dismukes of the ABCs and Harold Treadwell of the Bacharachs had a short-lived double shutout. Then it was off to Norfolk for a game the next day, followed by at least one game each day in Virginia, Maryland, Delaware, or Atlantic City through August 9. Such was the itinerary of barnstorming Black baseball clubs.

Sources

Negro League player statistics were not always reliably and completely compiled in the years the games were actually played. But efforts have been made in recent years to use box scores and game stories to retroactively compile annual stats. Redding’s and Johnson’s pitching wins are from the Seamheads.com Negro Leagues Database, considered the most complete of the efforts.

Notes

1 “Bacharachs Revel in Hits and Runs,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, August 1, 1921; “Bacharachs and A.B.C.s Play to Big Crowd,” Chicago Defender, August 6, 1921; “Baseball Results,” New York Age, August 6, 1921.

2 “Bacharachs Revel in Hits and Runs.”

3 Erin Blakemore, “The ‘White Slavery’ Law That Brought Down Jack Johnson Is Still in Effect,” https://www.History.com, May 24, 2018 (updated February 25, 2019).

4 James E. Overmyer, Black Ball and the Boardwalk: The Bacharach Giants of Atlantic City, 1916-1929 (Jefferson, North Carolina, McFarland, 2014), 52.

5 “Baseball Results.”

6 “Bacharachs and A.B.C.s Play to Big Crowd.”

7 “Bacharachs Revel in Hits and Runs.”

Additional Stats

Atlantic City Bacharach Giants 11

Indianapolis ABCs 3

Ebbets Field

Brooklyn, NY

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.