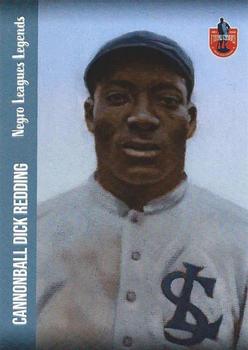

Dick Redding

Dick “Cannonball” Redding pitched professionally from 1911 to 1936 and got his nickname from his blazing fastball that knocked back catchers.1 Redding claimed he once fired a brand-new baseball against the side of a building and the ball broke apart.2 His velocity was so legendary that some historians have wondered if Redding was the hardest-throwing pitcher of all time.3

Dick “Cannonball” Redding pitched professionally from 1911 to 1936 and got his nickname from his blazing fastball that knocked back catchers.1 Redding claimed he once fired a brand-new baseball against the side of a building and the ball broke apart.2 His velocity was so legendary that some historians have wondered if Redding was the hardest-throwing pitcher of all time.3

Redding was durable; he frequently started games on back-to-back days and sometimes started both ends of doubleheaders.4

He was also known for his odd superstitions. “Redding wore the same sweatshirt to pitch for five days in a row. At the end of the five days that sweatshirt could stand up by itself. They made him wash it, and the next day he got knocked out of the box in the first inning. Claimed he’d lost all his strength,” former Negro Leagues shortstop Frank Forbes remembered.5

Cannonball’s full name was Richard Redding, and he was born in Atlanta on April 15, 1890. He was raised by his mother Laura Redding, who was born in Georgia in 1866 and worked as a laundress. Laura’s maiden name was Ford. Cannonball had two siblings, an older sister Minnie, who was born in Georgia in 1887, and a younger brother Leon, who was born there in 1898.6

As an amateur, Redding played for the semi-pro Atlanta Deppins and also played for a hotel’s baseball team in Palm Beach, Florida.7 He stood six-foot-four, weighed 210 pounds, threw and batted right-handed, and author Greg Proops said Redding’s hands “were so huge he could hide a baseball in his palm.”8

While some sources say Redding was illiterate, he attended Morris Brown College in Atlanta.9 His professional baseball debut came with the Philadelphia Giants in 1911, a team led by 38-year-old player-manager Grant “Home Run” Johnson. Redding moved to the New York Lincoln Giants later that season and was managed by Hall of Famers Sol White and Pop Lloyd. Redding struck out 19 batters in his first Lincoln Giants game, a 12-0 shutout of Phillipsburg (a club from Yonkers, New York) at the Lenox Oval in Manhattan.10

As a young pitcher, Redding used a no-windup delivery and threw only fastballs. “From 1911 when he broke into fast company, until a few years ago he used nothing but his smoke ball. And it was impossible to hit it. I know, because I have tried,” Hall of Fame first baseman Ben Taylor said.11 Writer David Barr described Redding’s arsenal as “three pitches — fastball on the outer half, fastball down the middle and fastball inside. He had superb control.”12

On September 4, 1911, Redding pitched in the Lincoln Giants’ 6-5 win over the Cuban Stars of Havana at Hilltop Park, home of the American League’s New York Highlanders.13 The New York Tribune compared Redding to the great Christy Mathewson the day before his appearance at Hilltop Park, calling him “the ‘Black Matty.’”14

Redding was joined by fellow flamethrower Smokey Joe Williams in 1912 and they helped the Lincoln Giants finish first among Eastern Independent Clubs that year. “Redding boasted a 43-12 record, with several no-hitters,” in 1912, according to Wes Singletary’s book The Right Time: John Henry “Pop” Lloyd and Black Baseball.15

One of those several no-hitters was on August 28, in Atlantic City, New Jersey. Redding held the Cuban Stars hitless in the Lincoln Giants’ 1-0 win. “Redding’s speed was terrific, and the Cubans were helpless before his delivery,” the New York Press reported.16 Negro Leagues historian Gary Ashwill wrote in 2012 that this game “appears to be, for now, the earliest known Negro league no-hitter (that is, a no-hitter in a game between top-flight black professional teams in the U.S.), preceding Frank Wickware’s 1914 gem by two years.”17 Redding is credited with pitching 30 career no-hitters.18

He stayed with the Lincoln Giants for the next three years, helping them finish first among Eastern Independent Clubs in 1913 and 1915 and second in 1914. Redding moved across town to the New York Lincoln Stars midway through the 1915 season and won 20 consecutive games for them that year.19

Redding helped the Lincoln Stars finish tied for first with the Jersey City-Poughkeepsie Cubans among Eastern Independent Clubs in 1916. There was an often-printed tale that Ty Cobb refused to face Redding.20 It appears the story originated from an exhibition game on October 8, 1916, in Putnam, Connecticut. Cobb was scheduled to play for visiting New Haven in an exhibition that day, with Redding scheduled to pitch in relief for Putnam. “Cobb did not do much to talk about while he was in the game and by previous agreement stopped playing when it was half over when Cannonball Redding the great colored pitcher went in to work for Putnam,” the Norwich, Connecticut Bulletin observed.21 Putnam won 1-0, Redding struck out 11 of the 12 batters he faced,22 and the Bulletin said Redding “was given a great ovation by the crowd to whom he proved much more of an attraction than the high salaried Cobb.”23

It wasn’t the only time Redding outshined an American League icon. He struck out Babe Ruth three times on nine pitches in an exhibition against Ruth’s barnstorming team.24 Negro Leagues historian Larry Hogan believed “No one equaled Redding when it came to winning big games against major league competition.”25

Redding moved to the Chicago American Giants in 1917 and squared off with fellow early-1900s Black baseball ace John Donaldson on September 9. Redding started for the American Giants, Donaldson started for the All Nations, and both pitchers threw 12-inning complete games in the All Nations’ 2-1 victory. “While Donaldson came out on the long end of the score, Redding clearly outpitched him, as he allowed only two hits and struck out twelve men,” the Chicago Tribune reported the next day.26 The American Giants finished first among Western Independent Clubs in 1917. The media started calling him “Smiling Dick” that year and compared his overpowering pitching to Walter Johnson’s.27 Hall of Famer Rube Foster was the American Giants’ manager, owner, and business manager.

Nineteen seventeen was also the year that Redding registered for the U.S. military draft.28 He served in World War I and was assigned to the front lines in France.29 Negro Leagues author Lawrence Hogan discovered Redding was nicknamed “Grenade” because of his battlefield achievements.30

Redding returned to New York and pitched for the Brooklyn Royal Giants in 1918. He split the 1919 season between the Royal Giants and the Atlantic City Bacharach Giants, another club managed by Lloyd, who achieved the best record among Eastern independent teams, according to Seamheads.com. Redding stayed with Atlantic City from 1920-1921, which were his first two seasons as a player-manager. Atlantic City finished in second place among Eastern Independent Clubs in both of Redding’s seasons at the helm.

After pitching one year for the New York Bacharach Giants in 1922, Redding shifted back to a player-manager dual role from 1927 to 1933 with the Royal Giants. No longer reliant solely on fastballs, Redding added an extraordinary hesitation pitch.31

In a rare interview, Redding spoke at length about his pitching philosophy to the Burlington, Vermont Free Press before an exhibition there on July 4, 1929. “Speed is by no means the only asset of a successful pitcher, but it is a wonderful help if employed correctly,” Redding said. “I was not always able to put all of my weight behind the ball and I was often tired and lame after throwing a game. An old southern doctor told me two reasons for this. One, my fast one was overworked and secondly I did not get the right kind of exercise to take care of my arm muscles. Upon his advice I found out by practical experience, that the best exercise in the world to develop an arm to hurl the fast ones is to chop wood.”32

The Royal Giants played at Dexter Park in Queens, New York, for Redding’s first five seasons with the club, but they did not have an official home ballpark in 1933, his final season managing.33 Late in that season, Redding used a gut feeling to bring future legend Buck Leonard to the Negro Leagues. Leonard went to a bar that Redding frequented and asked Cannonball for a job. Even though Redding had never seen Leonard play, he agreed to give him a spot on the team.34 Leonard went on to become one of the best hitters in Negro Leagues history and he was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 1972. Leonard later said that Redding was “a nice fellow, easy-going. He never argued, never cursed, never smoked as I recall.”35

Redding pitched one game in relief for the Royal Giants in 1936 at age 46. A 1936 Brooklyn Times Union article said “Dick (Redding) no longer takes a regular turn in the pitching box for age has robbed him of his speed.”36 Throughout his playing career, Redding spent five off-seasons playing winter ball in Cuba.

Dick Redding’s life story took a saddening turn at the end. He was institutionalized at Pilgrim State Hospital, a psychiatric center in Brentwood, New York, on February 5, 1948. The reasons why Redding ended up there became a longstanding mystery. Researcher Ryan Whirty found a mention from 1948 in the Associated Negro Press that said Redding “is seriously ill and hospitalized at this writing, his body racked with a strange malady.”37

Redding passed away at the facility on October 31, 1948, at age 58. “I know he died in a mental hospital,” former Negro Leagues player Ted Page said. “Nobody’s ever told me really why, how, what happened to him.”38 Redding’s death certificate lists his cause of death as syphilis of the central nervous system.39

He left behind his wife Edna.40 They did not have any children. Redding was buried with honors at Long Island National Cemetery because of his military service in World War I.

“He was one of the finest men you ever saw,” said former Negro Leagues shortstop Jake Stephens. “He didn’t enjoy money, he just enjoyed life. He was just a clean-cut, clean-living man. There’ll never be another Dick Redding.”41

On April 19, 1952, the Pittsburgh Courier published lists of the best players in Negro Leagues history, based on its poll of 31 executives, journalists, and players who witnessed or participated in many Negro Leagues games. Redding was voted as a pitcher on the Second Team, with only Donaldson, Bill Foster, Satchel Paige, Bullet Rogan, and Williams listed ahead of him as pitchers on the First Team.

On February 3, 1971, the Baseball Hall of Fame and Major League Baseball announced the formation of a special committee to select former Negro League players for induction.42 Redding was mentioned in ensuing news articles predicting which Negro Leagues players would be enshrined in the coming years. For example, on February 4, 1971, the New York Daily News printed “a brief sketch of the 12 players observers of the Negro baseball leagues agree are the leading candidates for inclusion in the Hall of Fame.”43 The 12 players featured were Cool Papa Bell, Oscar Charleston, Ray Dandridge, Martín Dihigo, Josh Gibson, Monte Irvin, Judy Johnson, Leonard, Lloyd, Paige, Redding, and Williams. Eleven of those 12 players have since been elected to the Hall of Fame. Redding is the only one who has not.

That same edition of the Daily News quoted Hall of Fame manager Casey Stengel as saying “You can have Satchel Paige; I’ll take Cannonball Redding.”44

Thirty-five years later, Redding made it onto a Hall of Fame ballot. He was one of the 94 candidates on the 2006 Special Committee on the Negro Leagues’ initial ballot and was one of the 39 candidates that advanced to the final ballot, but he was not one of the 17 candidates that the committee voted into the Hall of Fame.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Steve Rice and Phil Williams and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also used Baseball-Reference.com, FamilySearch.org, Newspapers.com, and the Seamheads.com Negro Leagues database in January 2021.

Notes

1 Melancholy Jones, “Dick Redding, Atlantan, On All-Time Nine,” Atlanta Daily World, August 3, 1939: 3.

2 Jones, “Dick Redding.”

3 David Barr, “Give Them The Heater!” Monarchs to Grays to Crawfords, November 21, 2017, nlbm.mlblogs.com/give-them-the-heater-f4953a8b179f?gi=2f01485052e4

4 Dr. Layton Revel and Luis Munoz, “Forgotten Heroes: Dick ‘Cannonball’ Redding,” Center for Negro League Baseball Research, 2013, cnlbr.org/Portals/0/Hero/Dick-Cannonbal-Redding.pdf.

5 John Holway, “The Cannonball,” Baseball Research Journal, Society for American Baseball Research, 1980.

6 U.S. Census Bureau, 1900 U.S. Census.

7 Joe Posnanski, “The Baseball 100: No. 25, Pop Lloyd,” The Athletic, March 2, 2020.

8 Greg Proops, The Smartest Book in the World: A Lexicon of Literacy, a Rancorous Reportage, a Concise Curriculum of Cool (New York: Atria Books, 2015), no page number listed.

9 Timothy M. Gay, Satch, Dizzy, & Rapid Robert: The Wild Saga of Interracial Baseball Before Jackie Robinson (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2011), 28.

10 Wes Singletary, The Right Time: John Henry “Pop” Lloyd and Black Baseball (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland Books, 2011), 63.

11 Lawrence Hogan, Shades of Glory: The Negro Leagues & the Story of African-American Baseball (Washington: National Geographic, 2007), 130.

12 Barr, “Give Them The Heater!”

13 “Lincoln Giants win Two Games,” New York Tribune, September 5, 1911: 10.

14 “Baseball on the Hilltop,” New York Tribune, September 3, 1911: 12.

15 Singletary, The Right Time, 32.

16 “Redding Pitches Hitless Game,” New York Press, August 29, 1912: 7.

17 Gary Ashwill, “The First Negro League No-Hitter,” Agate Type, September 30, 2012. agatetype.typepad.com/agate_type/2012/09/the-first-negro-league-no-hitter.html

18 John Holway, “Is the Door Closing on Blacks?” Los Angeles Times, August 16, 1975: 8.

19 “Richard ‘Cannonball Dick’ Redding,” Negro Leagues Baseball Museum, nlbemuseum.com/history/players/redding.html

20 Red Smith, “2d-Class Immortality?” Binghamton, New York Press and Sun-Bulletin, February 21, 1971: 5E.

21 “Ty Cobb Fails To Show Much At Putnam,” Norwich, Connecticut Bulletin, October 9, 1916: 3.

22 “Keating Defeated By Putnam Team,” Bridgeport, Connecticut Times and Evening Farmer, October 9, 1916: 12.

23 “Ty Cobb Fails To Show Much At Putnam,” Norwich, Connecticut Bulletin, October 9, 1916: 3.

24 Paul Hoblin, Great Pitchers of the Negro Leagues (Minneapolis, Abdo Publishing, 2012), 33.

25 Hogan, Shades of Glory, 130.

26 “Beaten in 12th, Fosters Divide,” Chicago Tribune, September 10, 1917: 15.

27 “Redding,” Negro Leagues Baseball Museum.

28 United States World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918.

29 Gay, Satch, Dizzy, & Rapid Robert, 28.

30 Hogan, Shades of Glory, 146.

31 Singletary, The Right Time, 32.

32 “Cannon-Ball Redding Grows Philosophical On Art of Pitching,” Burlington, Vermont Free Press, July 1, 1929: 15.

33 “Dick Redding,” SeamHeads.com Negro Leagues Database, Redding’s manager page, seamheads.com/NegroLgs/manager.php?playerID=reddi01dic

34 Brad Snyder, Beyond the Shadow of the Senators: The Untold Story of the Homestead Grays and the Integration of Baseball (New York: McGraw Hill, 2003), 27.

35 Holway, “The Cannonball.”

36 Irwin N. Rosee, “Royal-Dexter Feud Oldest in Semi-Pro,” Brooklyn Times Union, May 14, 1936: 2A.

37 Ryan Whirty, “The Cannonball Mystery, Continued,” The Negro Leagues Up Close, www.homeplatedontmove.wordpress.com/2014/04/22/the-cannonball-mystery-continued/

38 Holway, “The Cannonball.”

39 New York State Department of Health, Division of Vital Statistics, Certificate of Death, November 2, 1948.

40 U.S. Census Bureau, 1940 U.S. Census.

41 Holway, “The Cannonball.”

42 Phil Pepe, “Old Negro Greats Get Chance at Hall of Fame,” New York Daily News, February 4, 1971: 91.

43 “Josh, Satch & Co. …Color ‘Em Great,” New York Daily News, February 4, 1971: 91.

44 “Josh, Satch & Co. …Color ‘Em Great.”

Full Name

Richard Redding

Born

April 15, 1890 at Atlanta, GA (USA)

Died

October 31, 1948 at Islip, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.