July 6, 1933: A Dream Realized: Comiskey Park hosts first All-Star Game; Babe Ruth homers

In 1933, Chicago was celebrating its centennial by hosting a World’s Fair, entitled A Century of Progress Exposition. Fair officials asked the local sports editors to think of an athletic event that would attract fans to Chicago from around the country.

In 1933, Chicago was celebrating its centennial by hosting a World’s Fair, entitled A Century of Progress Exposition. Fair officials asked the local sports editors to think of an athletic event that would attract fans to Chicago from around the country.

Arch Ward, sports editor of the Chicago Tribune, suggested a baseball game to be played at Comiskey Park matching the best players in the American League against the best players in the National League. Labeling it “the game of the century,” he was certain it would be a success. Fan interest was sure to be high, but to make it even more so, he would have the fans select the players. But before any announcement of such a game could be made, Ward had to ascertain if his dream was feasible. The first person he consulted was American League President Will Harridge.

Ward was prepared to drop the whole scheme if he could not get Harridge’s approval. To Ward’s delight, Harridge not only approved, he promised to recommend it to the eight American League club owners. The following day, Ward explained the plan to William E. Veeck, president of the Chicago Cubs. Veeck loved the idea and promised to lobby for the game with the other National League owners. A call by Ward to National League President John Heydler also elicited a promise to discuss the proposed game with those owners.

On May 9, at a special meeting in Cleveland, the American League owners enthusiastically voted in favor of the game and chose July 6 as the date. However, a few days later, Ward received a telegram from Heydler informing him that three NL owners — the Giants’ Charles Stoneham, the Braves’ Charles Adams, and the Cardinals’ Sam Breadon — had turned down the idea.

Breadon based his opposition on the fear that any future games, as this one was doing, would be forced to donate the proceeds to charity. Stoneham and Adams opposed the idea because of the selected date. The Giants and Braves were scheduled to play a doubleheader in Boston on July 5, making it impossible for any chosen players to be in Chicago in time to play on July 6.

Breadon dropped his opposition after Ward convinced him that other cities, including St. Louis, could benefit by hosting a future All-Star Game. The only obstacle remaining was the July 5 Giants-Braves doubleheader. After National League owners persuaded Heydler to postpone that doubleheader, a contract was signed by Ward, representing the Tribune, Heydler, and Harridge.

Editors at the Tribune had thought it unlikely other newspapers would do anything to help publicize a rival newspaper, yet all 55 Ward had asked to join in, accepted. In a gesture of cooperation, they even volunteered to help in the polling. The idea captured the imagination of fans everywhere, who then took the opportunity to vote for the players they most wanted to see.

Chicago White Sox outfielder Al Simmons, tied with Washington manager-shortstop Joe Cronin for the league lead in batting, got the most votes, 346,291. Philadelphia Phillies outfielder Chuck Klein, the National League’s leading hitter, was also its leading vote-getter, with 342,283.

The final rosters, 18 players per league, were determined by a combination of the fans’ votes and the selections of the respective managers. The players would not be paid for participating, but would benefit indirectly by the net receipts of $46,506 the game raised for the Association of Professional Baseball Players of America.

The two most honored managers in the game, one from each league, were selected to lead their respective teams. John McGraw had stepped down in June 1932 after 30 years at the helm of the New York Giants, but the National League called him out of retirement to manage this one game. The Americans gave the managerial honors to Connie Mack, who had led the Athletics since the league’s birth.

The regular season would resume the following day, although the owners had agreed that if the All-Star Game was rained out, they would cancel the next day’s schedule and play it then. That precaution proved unnecessary; the weather was perfect and though the country was struggling through the worst economic crisis in its history, every seat was filled.

For all sections of the park, patrons had been allowed to buy only four tickets, and there was no standing room. All seats were priced the same as for regular-season games at Comiskey Park, and because they played the game under “World Series rules,” no spectators would be allowed on the field. The crowd of 47,595, conducted itself in an exemplary manner, as if each fan knew he was witnessing something special.

The American League stars won the game, 4-2, but both sides offered strong pitching, solid hitting, and near-flawless defense. Yankees first baseman Lou Gehrig’s drop of Philadelphia Phillies shortstop Dick Bartell’s foul pop in the fifth inning was the game’s only error.

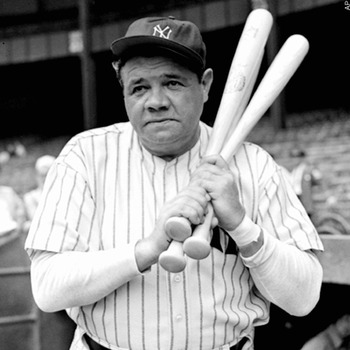

Babe Ruth, 38 years old and nearing the end of his career, provided the AL’s margin of victory with the first home run in All-Star competition, a third-inning two-run blast. It came off National League starter Bill Hallahan of St. Louis and increased the American League’s lead to 3-0.

Five days before the game, McGraw and Mack had announced that the starting pitchers would be Carl Hubbell of the Giants and Lefty Grove of the A’s, the game’s two best left-handers. But both managers changed their minds on game day, although both stayed with left-handers: McGraw went with Hallahan (10-4), while Mack chose the Yankees’ Lefty Gomez (9-6).

Current Giants manager Bill Terry captained the National Leaguers, who had the words “NATIONAL LEAGUE” on the fronts of their gray road uniforms with an “NL” emblazoned on their caps. Tigers second baseman Charlie Gehringer captained the Americans, each of whom wore his regular home uniform.

To help familiarize themselves with the other league, both teams used the other’s ball during batting practice to acclimate themselves to the different constructions. An American League ball, reputed to be livelier, would be used for the first 4½ innings, before the teams switched to the thicker-covered National League ball.

At 1:15 P.M., home-plate umpire Bill Dinneen of the American League called “Play Ball!” and Cardinals third baseman Pepper Martin stepped in as the first All-Star batter. Gomez retired him on a groundball to shortstop Cronin, and the “dream game” had become a reality. In the second inning, the American Leaguers scored the first All-Star run, helped along by the wildness of Hallahan, who not for nothing was known as “Wild Bill.”1 After walking White Sox third baseman Jimmy Dykes and Cronin, he yielded a two-out single to Gomez, a historically weak batter, that scored Dykes.

When Hallahan walked Gehrig following Ruth’s third-inning home run, McGraw replaced him with Cubs right-hander Lon Warneke. Meanwhile, Gomez held the National Leaguers scoreless in his three innings, as did Washington’s Alvin Crowder in the fourth and fifth. The Nationals finally broke through in the sixth. Warneke hit a one-out triple, a long fly down the right-field line that was poorly handled by Ruth, and scored as Martin was grounding out. Frankie Frisch, manager-second baseman of the Cardinals, followed with a home run to cut the AL’s lead to 3-2.

Warneke had already pitched three full innings, and had raced around the bases in the top of the sixth; nevertheless, McGraw sent him out to pitch the home half of the inning. The American Leaguers quickly got a run back on a single by Cronin, a sacrifice by Rick Ferrell, and a single by Cleveland’s Earl Averill, batting for Crowder. Ferrell, the Red Sox’ lone representative, caught the entire game, despite having finished third in the voting behind the Yankees’ Bill Dickey and Philadelphia’s Mickey Cochrane, both of whom were injured.

Hubbell and Grove came on in the seventh. Hubbell, who had shut out the Cardinals, 1-0, in 18 innings four days earlier, pitched two innings, blanking the American Leaguers on one hit. Grove pitched the final three innings for the AL, also allowing no runs, though the National Leaguers threatened in both the seventh and the eighth.

They had runners on second and third in the seventh, with just one out, but Grove struck out the Cubs’ Gabby Hartnett and got Hartnett’s Chicago teammate, Woody English, on a fly ball. Then in the eighth, with two out and Frisch, who had singled, on first, Hafey hit what would have been a game-tying home run in a park less spacious than Comiskey. Ruth ran it down and caught it with his back pressed to the right-field wall. Grove retired the National Leaguers one-two-three in the ninth, and the “game of the century” was over.

McGraw went to the winners’ locker room to congratulate Mack, his longtime rival, and Ruth, whom he had often denigrated in the past.

Both managers said they hoped the game would be repeated annually.

This essay was adapted from the author’s article on the 1933 All-Star Game that appeared in “The Midsummer Classic: The Complete History of Baseball’s All-Star Game” (Bison Books, 2001).

Sources

The author also accessed Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, and SABR.org.

Notes

1 Hallahan walked five in his two-plus innings, which remain the most walks given up by a pitcher in one All-Star Game.

Additional Stats

American League 4

National League 2

Comiskey Park

Chicago, IL

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.