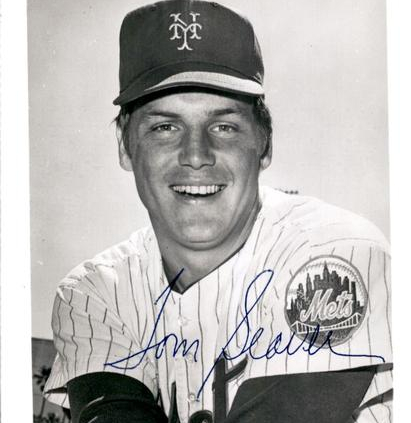

July 9, 1969: Tom Seaver’s near-perfect game

The atmosphere was positively electric at Shea Stadium on the night of July 9, 1969, as the Mets prepared to play the Cubs in the biggest game in Mets history. The upstart Mets, in only their eighth season of existence, were in a position that no one thought possible before the season — contending for first place against a powerful Cubs squad that led the NL’s Eastern Division by four games going into the July 9 game.1 It was a historic night and it would end in a historic game. The Mets’ young right-hander, Tom Seaver, came within two outs of a perfect game as the New Yorkers beat Chicago for the second straight day and established themselves as legitimate pennant contenders.

eighth season of existence, were in a position that no one thought possible before the season — contending for first place against a powerful Cubs squad that led the NL’s Eastern Division by four games going into the July 9 game.1 It was a historic night and it would end in a historic game. The Mets’ young right-hander, Tom Seaver, came within two outs of a perfect game as the New Yorkers beat Chicago for the second straight day and established themselves as legitimate pennant contenders.

The 1969 Cubs were one of the franchise’s all-time great teams. They had not won a World Series since 1908 or a pennant since 1945, and 1969 looked like the year of the Cubs. Led by their fiery and brilliant manager, Leo “The Lip” Durocher,” the team from the North Side featured a powerful offense, including three future Hall of Famers: “Mr. Cub” Ernie Banks at first, Ron Santo at third, and Billy Williams in left. Chicago also had a great catcher, Randy Hundley, and a solid middle infield combination with shortstop Don Kessinger and second baseman Glenn Beckert. Veteran Al Spangler shared right field with ex-Met Jim Hickman. The only weak spot in the lineup was center field, where little-known Don Young played most of the games, backed up by several others, including a 22-year-old rookie named Jim Qualls, who had a date with history.

The 1969 Mets had a winning record at midseason for the first time in their history. An expansion team in 1962, the Mets had set numerous records for futility. They lost a record 120 games in 1962 and then lost 90 or more games in each of the next five seasons (through 1967).2 Only in 1968 did the Mets finally lose less than 90 games, finishing in ninth place, one game ahead of last place Houston, with a record of 73-89. Former Brooklyn Dodgers star Gil Hodges, a fan favorite, took over as the Mets manager in 1968 and his steady hand had the team in pennant contention by the summer of 1969.

In contrast to the Cubs, the Mets’ offense was weak, featuring catcher Jerry Grote, first baseman Ed Kranepool, second baseman Ken Boswell, shortstop Bud Harrelson, third baseman Wayne Garrett, and young outfielders Cleon Jones, Tommie Agee, and Ron Swoboda. The Mets’ strength was in their young pitchers, including their Big Three starters: 24-year-old Seaver, 26-year-old Jerry Koosman, and 22-year-old Gary Gentry. The bullpen included a fireballing 22-year-old right hander named Nolan Ryan.

The previous day at Shea, the Mets played the Cubs in the opener of a three-game series. Trailing the first-place Cubs by five games at the series start,3 the Mets won the opener in dramatic fashion, scoring three runs in the bottom of the ninth for a 4-3 victory. Thus, the stage was set for July 9, with their fans dreaming of a series sweep to put the Mets within a hair’s breadth of first place. On this night, it was the “All-American boy,” Tom Seaver, who would take the mound and try to lead the Mets to a place where they had never gone before.

Shea Stadium was packed with more than 59,000 screaming fans. What was about to unfold was not only one of the greatest games in Mets history, but one of the great games in baseball history, given the importance of the game, the record crowd, and the performance of a second-year pitcher who would go on to make the Hall of Fame.

Opposing Seaver was the Cubs’ ace lefty Ken Holtzman. Holtzman was only 23 years old and yet in his fifth season with the Cubs. This, however, would not be Holtzman’s night. The Mets scored one run in the first and had scored two runs in the second when Durocher pulled Holtzman for reliever Ted Abernathy, who ended the inning. The Mets led 3-0 after two and they had all the runs that they would need.

Seaver joined the Mets in 1967, one year removed from a stellar college career at the University of Southern California. He was a big, strong right-hander with near-perfect mechanics and his arrival gave Mets fans hope that their beloved team would finally become a winning one. Seaver lived up to his billing, going 16-13 in 1967 with a 2.76 ERA and 16-12 in 1968 with a 2.20 ERA. He was off to a spectacular start in 1969, with a 13-3 record going into the big game against the Cubs. The Mets had played the Cubs eight times early in the season, winning only three, at a time when the Mets had their usual below-.500 record. This time was different. As Seaver took the mound on that balmy July evening, the Mets were 46-34 and in a pennant race. For Seaver, it was the biggest game of his young major-league career, on the biggest stage, before the largest crowd in Shea Stadium history.4

“Tom Terrific” lived up to his nickname that evening. The Cubs could not touch him. He was pumped, as he struck out five of the first six Cubs batters. The fans were really into it and by the sixth inning it became apparent that on this, the biggest night in Mets history, Tom Seaver was making history. He was pitching a perfect game. No Mets pitcher had done so. No Mets pitcher had thrown a no-hitter and here was Seaver having retired the first 15 batters. The Cubs went down in order again in the sixth and the perfect game was intact. Seaver received a tremendous ovation as he came to bat in the bottom of the frame.

In the Cubs seventh, once again it was three up and three down and you could feel the tension as the excited crowd appreciated the magnitude of what was unfolding before their eyes. The Mets added a run in the seventh, to make it 4-0, but the story of the night now was Seaver. The Mets made some defensive changes in the eighth as Seaver prepared to face the middle of the Cubs lineup. He retired Santo on a fly to center and then struck out the great Banks and then Spangler, to give him 11 strikeouts.

Through eight innings of pitching, it was 24 up and 24 down, 11 on strikeouts. Seaver looked strong as he continued to pump fastballs and the nearly 60,000 faithful could feel his adrenaline as the game moved to the ninth inning.5

Randy Hundley led off. Surprisingly, Hundley tried to bunt his way on. As the boos sounded, Seaver fielded the bunt and threw to first for the out.6 Two outs to go for a perfect game. The fans were on their feet screaming. Up came the weakest hitter in the Cubs lineup — that 22-year-old rookie by the name of Jim Qualls. Qualls was making only his ninth start of the season and came into the game batting only .244. He would have only 120 at-bats in 1969 and after nine at-bats in 1970, for Montreal, he was gone for good from the major leagues. But on this night, on the night that Tom Seaver would make history, the names Jim Qualls and Tom Seaver would forever become linked in baseball lore.

On the first pitch, Seaver came in with a fastball and Qualls (a switch-hitter batting lefty) hit it to the left of second and in front of center fielder Agee — a clean single. Suddenly, the noisy crowd went completely silent. It was an eerie feeling at Shea. All of the air had gone out of the balloon. The disappointment that Seaver felt was shared by the suddenly quiet crowd. 7 Then came the standing ovation for Seaver. The next two batters were retired and the game was over.

The Mets had a huge victory against the Cubs. They were now only three games out of first place.8 The Franchise, Tom Seaver, had come through. He had pitched the greatest game in Mets history. Despite the disappointment caused by Qualls, Mets fans went home satisfied. They had just witnessed a game that, although not perfect, changed the course of Mets history. Seaver’s dominance of the Cubs that night showed, against all odds, that this team was a legitimate pennant contender. As Seaver went on to win 25 games in that magical season, the Mets won the pennant and the World Series. Their performance earned them the moniker “The Miracle Mets.” The Miracle began on July 9, 1969.

Author’s note

The author sat in the Upper Deck that evening and nearly 50 years later still vividly recalled the excitement and tension of that night, including how an unbelievably loud crowd went completely silent at the moment Qualls’s hit landed in center field.

Sources

Retrosheet (retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1969/B07090NYN1969.htm) and Baseball Reference.com (baseball-reference.com/boxes/NYN/NYN196907090.shtml) were the source of play-by-play information.

Notes

1 There is a discrepancy between Retrosheet and Baseball-Reference.com with respect to the NL standings, and how many games behind the Mets were, on July 8 and 9, 1969. The references herein are based on Retrosheet, which is correct. On June 15, 1969, the Cubs played a doubleheader, losing the first game. The second game was suspended at the end of the seventh inning and completed on September 2, with the Cubs winning. Retrosheet correctly recorded only the June 15 first-game loss in the standings through September 1, recording the Cubs’ win in the suspended game only on September 2 when it was completed. Baseball Reference.com counted the September 2 suspended-game victory as a win in the standings on June 15, the day the game was suspended.

2 The Mets finished last from 1963 through 1965, losing 111, 109, and 112 games respectively. In 1966, the Mets were 66-95 and escaped the cellar for the first time, finishing ninth (of 10). In 1967, the Mets were back in last place as they lost 101 games.

3 See n. 1.

4 Shea Stadium’s capacity in 1969 was 55,300. On July 9, 1969, there were 59,083 fans in attendance. As reported in the New York Times, the paid attendance of 50,709 “was swelled by some junior fans who had been promised tickets in a long-planned promotion. Every seat could have been sold and many fans were turned away.” George Vecsey, “Single by Rookie Only Chicago Hit,” New York Times, July 10, 1969.

5 Even though Seaver looked strong, he said afterward that “the feeling was almost gone from my arm.” Ibid. In 1969 batters did not work the count and Seaver’s gem took only 99 pitches and 2 hours 2 minutes to complete.

6 After the game, Mets first baseman Donn Clendenon said he was not upset with Hundley’s effort to bunt his way on to break up a perfect game, commenting, “I don’t think Hundley was thinking about the no-hitter. … He was just trying to get on and start a rally.” Al Harvin, “Mets Clubhouse Quieted by Single,” New York Times, July 10, 1969.

7 Seaver said,. “I felt as if somebody had opened up a spout in my foot and the joy all went out of me.” Pack Bringley, “Even Tom Seaver Wasn’t Perfect,” amazinavenue.com/2013/4/1/4164470/tom-seaver-mets-imperfect-game-cub, April 1, 2013. While disappointed after the game, Seaver commented, “I got my breaks. … I just needed one more break.” Vecsey, “Single by Rookie Only Chicago Hit.” Forty years after the game was played, Seaver still vividly recalled the emotions of that evening, stating that after the game “The very first thing I felt might have been something like, ‘what could have been,’” Michael Bamberger, ”Forty Years Ago, Little-Known Qualls Spoiled Seaver’s Bid at Perfection,” si.com/more-sports/2009/07/08/seaver-tribute, December 11, 2017.

8 See n.1.

Additional Stats

New York Mets 4

Chicago Cubs 0

Shea Stadium

New York, NY

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.