June 28, 1911: Mathewson shuts out Boston in Giants’ first game at new Polo Grounds

The Polo Grounds was an odd name for an odd series of stadiums in different parts of New York. The final Polo Grounds opened on June 28, 1911, less than three months after the previous one was destroyed by fire.

The first Polo Grounds was aptly named, as it was a polo field, extending from Sixth Avenue to Fifth Avenue and wedged between 110th and 112th Streets just north of Central Park. Professional baseball first arrived in 1880, and two major-league teams — New York (later to take the name Giants) of the National League and the Metropolitan of the American Association — in 1883 used the Polo Grounds, which had separate diamonds and grandstands at opposite ends of the site.

In 1889 the city cut a street through the Polo Grounds, evicting the New York Giants. (The Metropolitan no longer existed.) The Giants found a new place to play on the southern portion of Coogan’s Hollow, beneath the 155th Street viaduct, squeezed in between a bluff and a river. To help keep continuity with their fans, the Giants carried the name uptown, christening another Polo Grounds (first known as the New Polo Grounds). The name could have just as easily been lost to history, but it lived and carried to another pair of stadiums.

A new ballpark opened on the northern lot of Coogan’s Hollow, adjacent to Polo Grounds, in 1890. It was first used by the New York team in the Players League and was known that season as Brotherhood Park. With the demise of the Players’ League after one season, the Giants of the National League moved in, taking along the name Polo Grounds again, in 1891.

This version of the Polo Grounds was a wooden structure with a bathtub shape, mostly open in the outfield, which created space for people to watch the game from horse-drawn carriages. It was the site of one of the most famous plays in history — Merkle’s Boner — in 1908 when the Giants had the winning run in a game nullified by Fred Merkle, who had been on first when Al Bridwell hit an apparent game-ending single, abandoned the basepaths before reaching second.

The Giants played the first two games of the 1911 season on the Polo Grounds, but an overnight fire after the second game destroyed the grandstand, forcing the Giants to move into nearby Hilltop Park with the New York Highlanders (also known as the Yankees) of the American League as they figured out what to do for a new ballpark.

Giants owner John T. Brush wanted to rebuild the Polo Grounds on the same spot but with more durable building materials. Author Noel Hynd provides a touching story of Brush, who used a wheelchair because of locomotor ataxia, coming back to the site with his wife, Elsie, and saying, “I want to build a concrete stand. The finest thing that can be constructed. It will mean economy for a time. Are you willing to stand by me?”1 She was.

Brush needed more than just Elsie’s support, he needed a long-term lease. Even before the fire, Brush had wanted to erect a permanent stand to replace the wooden amphitheater but was reluctant to do so because of the short lease he then had. He soon worked out a 25-year lease with the property owners and charged ahead with plans for a grand edifice and the erection of a grandstand with reinforced concrete, marble, and structural steel.2

Brush planned to drop the Polo Grounds name and tout his contribution to the new structure by calling it Brush Stadium. Fans and news reporters had other ideas, though, and the name Polo Grounds persevered. As Lawrence S. Ritter said of the rebuilt structure in his book Lost Ballparks, “Polo Grounds it had been and Polo Grounds it would remain.”3

With more than 2,000 piles driven 25 to 40 feet in the ground to ensure a solid foundation, a lower tier equipped with chairs was in place for the Giants upon their return from a long road trip in late June.4 “Everything in connection with the building is fireproof,” wrote John Foster in Baseball Magazine. “A fire could be built in the center of the stand and have no effect upon the walls, flooring, or foundation.”5

Construction was ongoing, but more than enough seats were available when the Giants hosted the Boston Braves (known informally as the Rustlers at the time)6 in the first game of the final version of the Polo Grounds on Wednesday, June 28, 1911. The New York Times reported that the grandstand had 16,000 available seats with 10,000 more available in the outfield bleachers that had survived the fire.7

Far less than a sellout showed up, with attendance estimates provided by New York newspapers listing figures from 6,000 to 15,000.8 All accounts agreed that it was a hot day, which may have kept the crowd down. The bleachers, as always, were uncovered, and the unfinished ballpark left fans in the grandstand without a second deck to provide shade. The Giants installed a temporary canvas on top of the permanent seating area, but this provided relief only to those in the top rows. Owner John T. Brush also sweated, but he did it from a vantage point in his automobile from right field.

The main attraction may have been less about the new ballpark and more about the return of colorful, cocky New York favorite Turkey Mike Donlin, who had left baseball after the 1908 season to pursue acting with his wife, Mabel Hite. Donlin came back to the Giants in June 1911 and played three games on the road. Before the first game in New York, he made an ostentatious entrance amid flower bearers in center field.

The pitching matchup featured a pair of Mattys, Al Mattern for last-place Boston and Christy Mathewson for first-place New York. Through five innings, the Mattys dominated, each giving up five hits without a walk. Boston bunched its hits a bit more, but Mathewson worked out of the innings, helped by a few breaks and his fielders. Bill Sweeney led off the game with a single but was thrown out stealing by Jack “Chief” Meyers. With two out, Buck Herzog doubled and was stranded when Doc Miller grounded out.

With one out in the fourth, Herzog and Miller singled, although the latter’s was costly, as his grounder hit Herzog and put him out. Meyers then threw Miller out stealing. A single to start the fifth by Scotty Ingerton led nowhere as Mathewson retired Harry Steinfeldt, Johnny Kling, and Al Kaiser. Mattern started the sixth with a single and got to third after a sacrifice and groundout, but Herzog flied out.

The Giants broke the scoreless duel in the sixth when, with one out, Larry Doyle homered, the first home run in the final iteration of the Polo Grounds. Most of the news accounts say that Doyle hit the ball into the new grandstand in right field, but The Sun (New York) has it as an inside-the-park home run: “Doyle gave the ball a prodigious whack and dropped it in the extreme right wing of the stadium. While it was bouncing around on the concrete, he jogged around the bases.”9

Boston threatened in the seventh. Ingerton bunted down the third-base line. Art Devlin let the ball roll, hoping it would go foul, but it struck the base for a single. Steinfeldt bounced one through the right side. Ingerton hesitated rounding second and then went for third, only to be nailed by a strong throw from right fielder Red Murray. Kling hit a long drive to center, but Snodgrass corralled it with a running one-handed catch.

Mattern tired in the bottom of the inning, giving up a one-out single to Bridwell and walking Devlin. He compounded his problems with an errant pickoff throw to second, allowing the runners to advance. Mattern intentionally walked Meyers to bring up Mathewson, who produced a fly to left deep enough to score Bridwell. Josh Devore, who had a hit and had struck out twice, was next up, but John McGraw sent up Fred Merkle instead. Merkle had been scratched from the starting lineup after being struck in the groin in an early practice the Giants held that morning. Hitting for Devore, he drew a walk to load the bases. A wild pitch brought in Devlin with the Giants’ third run, with Meyers going to third. New York tried a double steal, pinch-runner Beals Becker taking off from first to lure a throw as Meyers broke from third. However, the return throw to the plate was in time to get Meyers and end the inning.

Mathewson retired six of the final seven Boston batters, Fred Tenney getting a leadoff single in the ninth, and New York had a 3-0 win in its first game back beneath Coogan’s Bluff. Despite his grand return, Mike Donlin did not play in the game.

Construction continued on the Polo Grounds over the next three months, interrupted only when the Giants were playing, and the work was complete by the 1911 World Series, which the Giants played in, losing to the Philadelphia Athletics, four games to two.

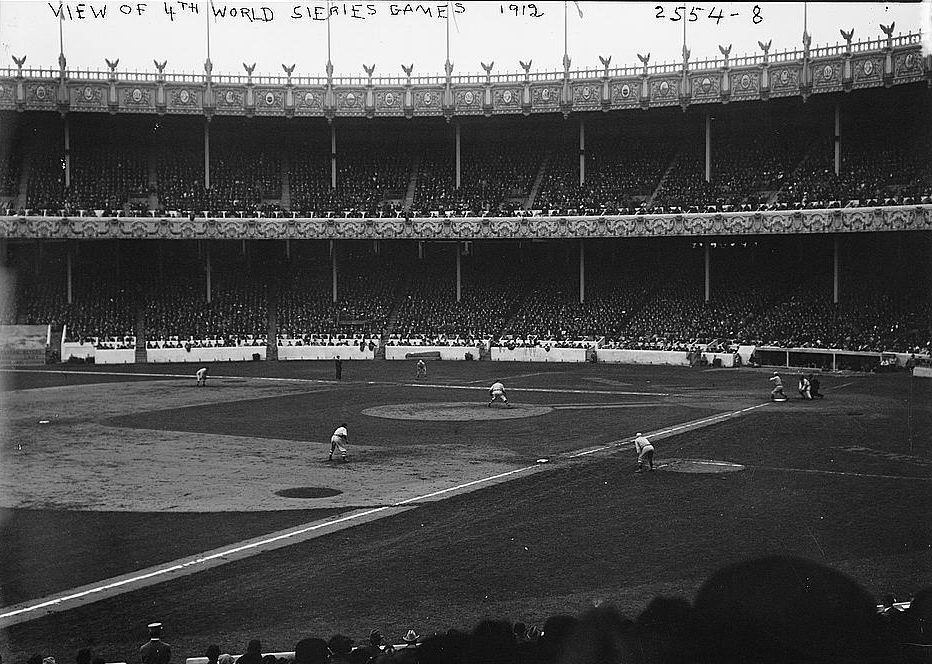

The completed Polo Grounds had a double-decked grandstand in a J-shape, the stands reaching approximately 40 feet into fair territory in right field but stopping short of the foul line in left field. The upper deck was faced with a decorative frieze containing a series of allegorical treatments in bas relief, while the façade of the roof was adorned with the coats of arms of all National League teams.

The ornamentation went away with a 1920s expansion that extended the grandstand, curving both sides toward one another in the deepest reaches of the outfield. Rather than meeting in center field, however, the stands stopped. Bleachers filled the gap on each side with a large building containing the locker room and team office dividing the two bleachers. The building was set back from the field, creating a notch in the playing area.

With the distance to extreme center field listed as anywhere from 475 to 505 feet — as the distances down each foul line were well short of 300 feet — the final version of the Polo Grounds, which closed in 1963, had achieved the distinction of the “oddest of the odd.”

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted Retrosheet.org and the following newspaper articles:

Bulger, Bozeman. “Pennant-Hunting Giants to Hold House-Warming at Polo Grounds,” New York Evening World, June 28, 1911: 13.

“Giants Again at Home,” New York Tribune, June 29, 1911: 8.

“Giants Welcomed Home by 15,000,” New York Evening World, June 28, 1911: 2.

“Only One Matty When It’s Over,” Boston Globe, June 29, 1911: 8.

https://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/NY1/NY1191106280.shtml

https://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1911/B06280NY11911.htm

Notes

1 Noel Hynd, The Giants of the Polo Grounds (New York: Doubleday, 1988): 163.

2 “Giants Get Lease on Polo Grounds,” New York Times, April 23, 1911: C5.

3 Lawrence S. Ritter, Lost Ballparks (New York: Viking Studio Books, 1992), 161.

4 John T. Brush, “The Evolution of the Baseball Grandstand: A New Era in the Development of the National Game,” Baseball Magazine, April 1912: 2. “The Stadium for the New York Baseball Club,” Engineering Record, July 29, 1911, Vol. 64, No. 5: 126-127.

5 John Foster, “The Magnificent New Polo Grounds: The Greatest Ball Park in the World,” Baseball Magazine, October 1911: 6.

6 Ed Coen, “Setting the Record Straight on Major League Team Nicknames,” SABR Baseball Research Journal, Vol. 48, No. 2, 2019: 69-70, writes that the team had no accepted nickname in 1911. In the coverage of this game, most of the newspapers, including the Boston Globe, referred to Boston as the Rustlers although the New York Tribune used Terriers as the nickname.

7 “Giants Reopen Polo Grounds and Win,” New York Times, June 28, 1911: 9.

8 The Times had the attendance at 6,000. The New-York Tribune had 10,000; the Evening World had 15,000.

9 “Celebrated with a Shutout,” The Sun (New York), June 29, 1911: 5.

Additional Stats

New York Giants 3

Boston Rustlers 0

Polo Grounds

New York, NY

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.