May 16, 1897: Arrested on a day of rest: Cleveland Spiders challenge Sunday baseball

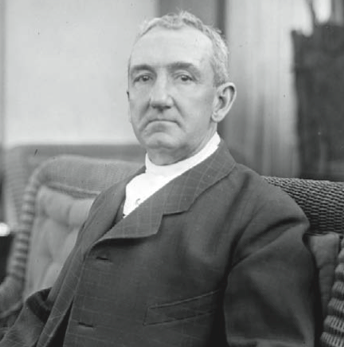

Stanley Robison, owner of the Cleveland Spiders, pushed the issue of Sunday baseball in 1897. When Robison lost in court, he sabotaged the team. (NATIONAL BASEBALL HALL OF FAME LIBRARY)

All Frank Robison and Stanley Robison wanted was for their Cleveland Spiders to make as much money as possible. That meant scheduling home games when fans could watch them.

But scheduling at convenient times was a tough proposition before the turn of the century, an age of six-day, 50-hour work weeks. Even given the usual 3 p.m. starting time for games, that left only Sunday as a day when most potential fans could easily come to the park. And Sunday baseball was illegal in Ohio.

In 1897 the Robisons challenged the law, which they felt was not only wrongheaded but inequitably enforced. They noted that Sunday baseball was being played openly in Cincinnati, where city and state officials looked the other way. Less than a year earlier, the Reds had drawn a record crowd of 24,000 to a Sunday game with the defending champion Baltimore Orioles. The Robisons wanted that revenue. They also needed it because attendance in Cleveland badly lagged behind the team’s performance, which had included a Temple Cup victory in 1895 and a runner-up finish in 1896.

If Sunday baseball was not permitted, the Robisons announced, they would consider relocating the team to a more tolerant city. Speculation fed the threat. “Cleveland is the poorest patronage of the League cities, but has one of the strongest teams to represent it,” observed The Sporting News, which added that “the Cleveland team in St. Louis would be a gold mine to its owners.”1

But Robert McKisson was mayor of Cleveland, and McKisson was an archfoe of Sunday ball. In that he had the support of unlikely allies: several of the city’s churches as well as the local saloon league. The churches’ motivation was obvious and—once you thought about it—so was the saloon keepers’. Unlike ballparks, the law did not force the closing of saloons on Sunday, making that day their best for revenue. Neither the churches nor the saloon owners craved the competition the Robisons’ Spiders would provide. “Men and boys will … go to the games and spend the 75 cents they would otherwise leave with us,” a tavern keeper told Sporting Life.2

The first of the Sunday games on Cleveland’s 1897 schedule was to be played on May 16, and McKisson made it known in advance that he was prepared to make a scene. Privately, he and the Robisons worked out a more civil arrangement. The game would be allowed to begin, but it would be halted after a single inning, the players arrested and one prosecuted in what amounted to a test case of the state law. The Robisons cooperated by disbursing “rain checks” to each paying fan—and there were an estimated 10,000 of them. Spiders Stanley Robison, owner of the Spiders, pushed the issue of Sunday baseball. When Robison lost in captain Patsy Tebeau juggled his lineup, inserting rookie pitcher Jack Powell at first base and designating him as the player to be formally charged. The game was in fact halted after a scoreless first inning, and the players on both teams (along with umpire Tim Hurst) were led away to be booked at the police station, where they signed autographs for the arresting officers. All were released on $100 bail posted by Frank Robison.

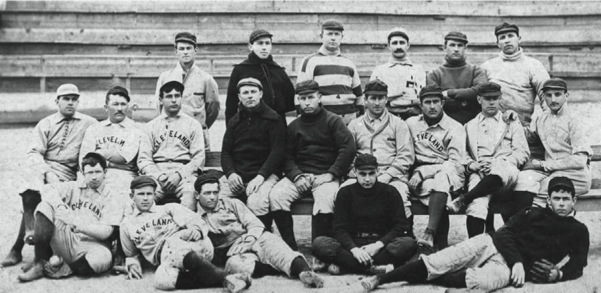

1898 Cleveland Spiders, many of whom were members of the 1897 team. (NATIONAL BASEBALL HALL OF FAME LIBRARY)

Immediate reaction in the press favored the players. “About seventy-five games of ball were played in the city yesterday, the police not interfering,” alleged Elmer Bates, Cleveland’s correspondent to Sporting Life.

But that had little impact in the courts. Powell was quickly tried and convicted, prompting Robison to cancel a game scheduled for Sunday, May 23. Powell, funded by Robison, appealed, contending that the prohibition essentially forced him to observe a religious holiday against his will. When Judge Walter Ong rendered his ruling in August, he sided with Powell and threw out the law. Although the state appealed that decision to the Ohio Supreme Court, the Robisons were for what remained of 1897 free to play Sunday ball. “It means,” wrote Bates, “that 20,000 workingmen, heretofore deprived of an opportunity of seeing a National League game, can with perfect assurance of two hours of rare enjoyment go out to League Park on Sunday afternoon without fear of police interfering in their effort to enjoy personal liberty.”3 They staged six such games, drawing a crowd in excess of 14,000 to the July 25 game with Baltimore. It was the largest baseball crowd in the city until 1902.

But the Robisons’ victory was short-lived. In April of 1898, the Ohio Supreme Court reversed Ong and upheld the ban on Sunday ball. The ruling effectively killed the Spiders. Opening Day attendance that season barely topped 1,000, driven downward both by the ruling and by the owners’ renewed threats to move the team. When the Robisons’ ongoing efforts to play Sunday games in a small town outside Cleveland were again thwarted by local sentiment, they reacted by taking the team on the road … permanently. From late June until season’s end, the Spiders played just three more games at their home park, scheduling everything else either at neutral sites or at their opponents’ fields.

In 1899 the Robisons went further, transferring Cleveland’s best players — Cy Young, Lou Criger, Jesse Burkett, Bobby Wallace, Powell, Tebeau — to the St. Louis team, which they simultaneously owned. The moves effectively ransacked the 1899 Spiders … but that’s a separate story.

Did the Sunday baseball decision destroy National League baseball in Cleveland? Not necessarily, for it may have been doomed anyway. There is a line of argument that the NL, which had operated with a dozen teams since 1892, was inevitably bound to contract, that one of the Robisons’ two teams would have been liquidated, and that Cleveland was always the logical choice for that distinction ahead of St. Louis.

But if the events of May 16, 1897, and subsequent legal rulings did not kill the Spiders directly, they certainly ensured the franchise’s demise.

This essay was originally published in “Inventing Baseball: The 100 Greatest Games of the 19th Century” (2013), edited by Bill Felber. Download the SABR e-book by clicking here.

Notes

1 The Sporting News, March 27, 1897.

2 Sporting Life, February 13, 1897.

3 Sporting Life, June 19, 1897.

Additional Stats

Washington Senators

vs. Cleveland Spiders

League Park

Cleveland, OH

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.