May 2, 1887: The first African-American battery

Catchers have been prized from baseball’s beginning, as evidenced by the Knickerbocker rule requiring that a third strike be caught for the batter to be out.1 Casey Stengel had that in mind when he explained the Mets’ selection of a catcher with the first pick in the 1961 expansion draft. “You have to have a catcher or you’ll have a lot of passed balls,” Stengel remarked.2

In the early 1860s Jim Creighton effectively demonstrated, with his delivery of controlled fastballs, the value of good pitching. From that time forward the battery (pitcher and catcher) took on increasing significance.

Professional baseball’s beginnings in the early 1870s soon evolved into the “scientific” game, so the relationship between pitchers and catchers became more significant. It was not just the ability of one player to throw and the other to catch, it was also their ability to play the head game—conspiring with each other to outthink the batter. In the nearly all-white organized baseball of the 19th century, the idea of an African American battery trying to outwit their white opponents resulted in cultural implications that went beyond the outcome of an at-bat.

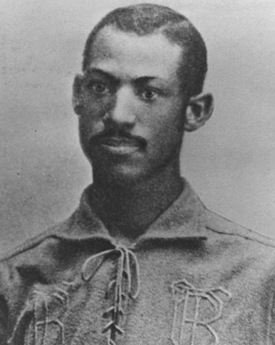

Given the prevailing attitudes, it is no wonder that professional baseball was almost two decades old before a pair of African American players constituted the battery of a team in organized baseball beyond the all-black teams of the day. Yet African American pitcher George Stovey and catcher Moses Fleetwood “Fleet” Walker stepped into this environment in the spring of 1887 as members of the otherwise all-white Newark Little Giants of the International Association.

Walker, 30, was an experienced and well-regarded catcher who was entering his fifth professional season, all on predominantly white teams, including the 1884 Toledo Blue Stockings of the major-league American Association. Walker was also a college man, having attended the University of Michigan and Oberlin College in Ohio. In addition, he had played in the Eastern League, a forerunner of the International League, in the two preceding seasons and was generally tolerated, if not liked, by his teammates.

Stovey, 20, was a pitching phenomenon in only his second season of organized baseball. He had the year before been lured away from the Cuban Giants by Jersey City, a league rival of Newark. He was signed by Newark for the ’87 season, precipitating a bitter contract dispute with the owners of the Jersey City club that Newark won.3

As the opening day of the season approached, Newark fans had high hopes for a league championship (they had won the Eastern League pennant the year before) and viewed the acquisition of Walker and Stovey as making an already strong team even stronger.

Although Walker would be placed in the lineup to catch white pitchers, Stovey was never matched up with any catcher other than Walker. On April 20, before the league season began, for example, Mickey Hughes, a white pitcher, was matched with Walker for a game against Waterbury,4 a team Walker had played for in 1885 and which was in the Eastern League in 1886. The next day, April 21, Stovey went into the box with Walker catching in a loss against the Brooklyn team of the American Association.5 On the 22nd Stovey rested while Walker caught against Bridgeport.

On April 26, the next time Newark played, Stovey was beaten by Jim Mutrie’s New York Giants, who played their regular starting lineup, which included five future Hall of Famers. Stovey was characterized as wild (with 11 runs and 14 hits allowed) while the work of Walker “behind the bat” was described as “absolutely perfect.” Walker also scored one of the three runs that pitcher Mickey Welch (one of the future Hall of Famers) gave up.6 It is reasonable to assume that Stovey needed a rest the following day, April 27; Walker was also held out of that exhibition game against Boston of the National League. Whether this was the result of any racial overtones is not recorded.

Walker caught Hughes in Newark’s 12–3 Opening Day victory over Buffalo.7 With no baseball on Sunday, it was an obvious choice to place the two players at the points of the battery for the teams’ second meeting on Monday, May 2. Stovey faced Michael Walsh, considered one of the International League’s best pitchers.

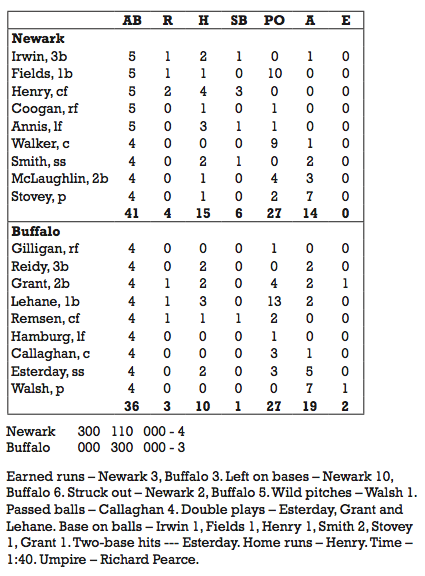

The game was described as a “splendid contest,” except that Walsh surrendered five walks and threw one wild pitch while battery mate Thomas Calihan allowed four passed balls. Newark scored three runs in the top of the first inning. Stovey kept the Buffalo club scoreless through its first three innings, but in the bottom of the fourth he allowed three hits, which produced three Buffalo runs.

With the score tied, Newark center fielder John Henry hit a solo home run over the left-field fence in the top of the fifth inning to give the home team a one-run lead. Stovey did the rest, not allowing Buffalo another run for the next five innings and securing a 4–3 victory for the Little Giants. Stovey also provided one of Newark’s 15 hits while allowing the opposition eight. Walker had no hits in four attempts but was his usual reliable self behind the plate.8

The next day Walker caught Hughes, and the day after that he again caught Stovey, who won his second game. In fact, Walker and Stovey combined for Stovey’s first ten games pitched that season, all of which were wins.

Notes

1 Henry Chadwick, Beadle’s Dime Base-Ball Player: A Compendium of the Game; First Rules of Baseball, Section 5 (New York: Irwin P. Beadle & Co. 1860), p. 7.

2 Peter Morris, Catcher, How the Man Behind the Plate Became an American Folk Hero (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2009), p. 39.

3 Brian McKenna, “George Stovey”; SABR Bioproject, http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/8ff10f5c.

4 Newark Evening News, April 21, 1887, p. 4.

5 Newark Evening News, April 22, 1887, p.1.

6 Newark Evening News, April 27, 1887, p. 4.

7 Newark Evening News, May 3, 1887, p. 1.

8 McKenna, SABR BioProject.

Additional Stats

Newark Little Giants 4

Buffalo (IL) 3

Newark Base Ball Grounds

Newark, NJ

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.