May 2, 1917: Fred Toney and Reds prevail 1-0 in double no-hitter against Cubs’ Hippo Vaughn

On May 2, 1917 the Cincinnati Reds and Chicago Cubs squared off at Chicago’s Weeghman Park for the first game of a four-game series. At 10-7 the Cubs sat in second place, only a half-game back of the eventual National League champion New York Giants. The Reds were in sixth place with a mark of 9-10, but were only 2½ games off the pace in the still young season.

On May 2, 1917 the Cincinnati Reds and Chicago Cubs squared off at Chicago’s Weeghman Park for the first game of a four-game series. At 10-7 the Cubs sat in second place, only a half-game back of the eventual National League champion New York Giants. The Reds were in sixth place with a mark of 9-10, but were only 2½ games off the pace in the still young season.

On the mound for the Reds was Fred Toney, a big, powerful right-hander known for his strength and arsenal of pitches.1 The Tennessee native began his pro career with Winchester of the Blue Grass League in 1908 and quickly established himself as a top hurler, winning 45 games in 1909-1910, including a 17-inning no-hitter against Lexington on May 10, 1909, in which he fanned 19 batters.

Toney made his major-league debut with the Cubs on April 15, 1911, but it wasn’t until he was claimed off waivers by the Reds in 1915 that he finally blossomed, going 17-6 with a 1.58 ERA that was second best in the NL. Only Grover Cleveland Alexander had a better ERA than Toney’s 1.98 in 1915-1916, and he was one of the circuit’s best pitchers again in 1917, going 4-1 with a 2.30 ERA prior to the May 2 tilt.

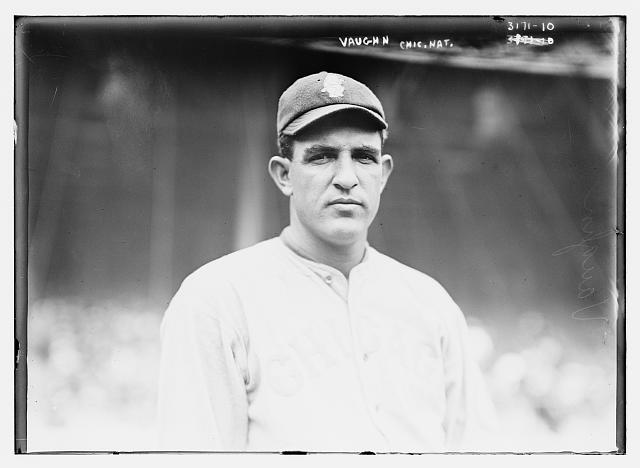

His mound opponent was Jim “Hippo” Vaughn, a 6-foot-4 left-handed behemoth known for his hard fastball and competitiveness.2 Vaughn’s pro career began a year before Toney’s, in 1907 with Corsicana of the North Texas League, and he made his major-league debut with the New York Yankees on June 19, 1908.

But, like Toney, it took a change of scenery before Vaughn became a consistent winner; from 1913, his first season with the Cubs, until 1920, his last winning season, Vaughn won 148 games and posted a 2.14 ERA, second in the NL to Alexander over that period. On May 2 Vaughn was 3-1 with a 2.25 ERA and had just beaten the Reds on April 25, striking out a season-high 11 batters in a 4-2 complete-game victory.

Conditions were less than favorable for a ballgame. It was cold and blustery as a stiff breeze blew off Lake Michigan, and the field was “soggy and slow” from recent rains.3 Jack Ryder of the Cincinnati Enquirer reported that only 2,500 brave souls were there to witness baseball history, over 2,000 less than average for Weeghman Park that year.4

Third baseman Heinie Groh led off the game for the Reds and fanned, then shortstop Larry Kopf grounded out. Greasy Neale, Cincinnati’s regular left fielder who was in center to fill in for an injured Edd Roush, belted a long drive to center field, but Cy Williams corralled it for the third out of the inning. It would be the only Cincinnati ball to leave the infield for the next nine innings. Toney retired Rolly Zeider, Harry Wolter, and Larry Doyle in order to send the game to the second.

Toney said later that he didn’t like the conditions and didn’t have his usual stuff, but he continued to baffle Cubs batters with his assortment of pitches.5 Vaughn set down Hal Chase, Jim Thorpe, and second baseman Dave Shean in order in the second. Toney ran into a spot of trouble in his half, but worked out of a jam. Fred Merkle led off with a hot liner that was speared by Groh, Williams walked with one out and advanced to second on a grounder to third, but Art Wilson, the Cubs backstop, popped out to Kopf to end the threat. It would be the only time a Cub reached second.

Both pitchers easily retired the side in the third, then Vaughn had to escape a jam of his own when he walked Groh to lead off the fourth. Kopf bounded into a double play to clear the bases, but Zeider muffed Neale’s grounder to give the Reds a runner on first with two outs. Neale attempted to steal second, but was gunned down by Wilson to end the frame.

Toney had no issues in the bottom of the fourth, and Vaughn narrowly escaped with his no-hitter intact when Thorpe clubbed a long liner down the left-field line that landed just foul. But the big southpaw set the Reds down again without allowing a hit. Williams drew another free pass in the bottom of the fifth, Les Mann lined out to left fielder Manuel Cueto, then Wilson hit a pop fly to Shean, who purposely dropped the ball in hopes of turning a double play. He retired Williams at second but Wilson was safe at first. Cubs third sacker Charlie Deal smacked a long fly to center, but Neale made a nifty running catch to retire the side.

Through six innings neither team had sniffed a hit or gotten past second base. The fans sensed what was happening and began rooting for both pitchers.6

Vaughn took the hill for the seventh and ran the count on Groh to 1-and-2 before Groh snapped and gave home-plate umpire Al Orth his unsolicited opinion about Orth’s strike zone. Groh was ejected and replaced by Gus Getz, who walked in Groh’s stead. But Kopf grounded into his second double play of the game, and Vaughn easily retired Neale. Toney dispatched the Cubs again in the bottom of the seventh, and Vaughn did the same to the Reds in the top of the eighth.

Vaughn took the hill for the seventh and ran the count on Groh to 1-and-2 before Groh snapped and gave home-plate umpire Al Orth his unsolicited opinion about Orth’s strike zone. Groh was ejected and replaced by Gus Getz, who walked in Groh’s stead. But Kopf grounded into his second double play of the game, and Vaughn easily retired Neale. Toney dispatched the Cubs again in the bottom of the seventh, and Vaughn did the same to the Reds in the top of the eighth.

It was during the bottom of the eighth that Vaughn realized he was throwing a no-hitter.7 The Cubs lefty was so focused on keeping the game “well in hand” that he hadn’t realized he was only one inning away from tossing his first no-hitter. Toney was of the same mindset, just trying to keep the Cubs off the scoreboard until his boys finally broke through against Vaughn.8

Vaughn dispatched the Reds in the ninth, then Toney set down the Cubs in order and the game went into extra frames with both sides still without a hit. Getz led off the top of the 10th and skied a foul pop to Wilson for the first out. That brought up Larry Kopf, who had grounded out three times, including twice into rally-killing double plays. By his own admission Vaughn “grew careless” and took one chance too many.9

Kopf shot a drive between Doyle and Merkle, the latter making a diving effort to no avail. It was a clean hit and the double no-hitter was over. Though the hometown throng was disappointed, the fans gave Kopf a nice ovation for ending Vaughn’s masterpiece. Neale poked a fly ball to Williams for out number two and it looked as if Vaughn would escape with his shutout intact, but Williams misplayed Chase’s line drive and suddenly there were Reds at first and third with two outs.10 Chase stole second while Wilson wisely held the ball rather than risk Kopf scoring on a throw.

With two on and two out, Jim Thorpe topped a short grounder in front of the plate that rolled up the third-base line. Vaughn went after it, figuring Deal wouldn’t be able to race in from third in time to record the out. He also knew he wouldn’t get Thorpe, a former Olympic gold medalist, at first base, so he tried to scoop the ball to Art Wilson in an effort to nab Kopf at the plate.

Kopf slid safely past Wilson, who then dropped the ball. Chase attempted to score as well, but Wilson recovered in time to tag him out and end the inning.11 The Reds went up 1-0 and Toney needed only three outs to complete his no-hitter. He began the bottom of the 10th by fanning Larry Doyle. Up stepped Fred Merkle, the Cubs’ cleanup hitter, and he delivered a blow to left that looked as though it would not only end Toney’s no-hit bid, but also tie the score. “It looked like a home run into the left bleachers,” wrote the Commercial Tribune, “but little Mr. Cueto of Cuba dashed back until he hit the wall and then speared the ball over his head.”12

With two outs and a near miss it was up to Cy Williams to keep the Cubs alive. Williams wasn’t the hitter he’d been in 1916 when he led the National League in home runs, but he was still dangerous. In fact, he showed how dangerous he was when he fouled off two two-strike pitches, including a long line drive down the right-field line that landed a foot foul. Toney threw another ball to run the count full and some speculated he was going to walk Williams again to face the less threatening Leslie Mann, but he came back with a side-arm curve and Williams swung and missed to complete Toney’s historic no-hitter.

Never before or since have two pitchers thrown nine no-hit innings in the same contest.

This article was published in SABR’s “No-Hitters” (2017), edited by Bill Nowlin. To read more Games Project stories from this book, click here.

Notes

1 https://ourgame.mlblogs.com/2012/02/04/. “He threw a variety of stuff,” wrote John Thorn, Major League Baseball’s official historian, “spitballs, fastballs, curves, and an overhand sinker that faded away from left-handed batters just as [Christy Mathewson’s] ‘fadeaway,’ or screwball, once had.”

2 Bill James and Rob Neyer, The Neyer/James Guide to Pitchers: An Historical Compendium of Pitching, Pitchers, and Pitches (New York: Fireside, 2004), 411-412. “Big Jim Vaughn used to pitch the particular kind of ball a batter liked best just to show him that he couldn’t hit it,” Pete Alexander told Baseball Magazine in 1925, as reported by Neyer/James.

3 “The weather was bitterly cold,” wrote Jack Ryder of the Cincinnati Enquirer, “and it was a wonder that even so many fans turned out to shiver in the arctic breezes off the lake,” May 3, 1917.

4 Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org list that day’s attendance at 3,500; the Cubs averaged 4,678 fans per game at Weeghman Park in 1917.

5 “It was rather a cold day and I was not feeling in my best form when the game started,” Toney said. “I didn’t have so much stuff as I sometimes do for the first six innings.” Vaughn concurred. “The boys said [Toney] didn’t seem to have as much on the ball as usual,” Baseball Magazine, July 1917.

6 “Toney and Vaughn were both in magnificent form,” wrote Ryder, “working with the precision of a machine. As round after round went by without either side getting the suspicion of a safety the crowd became wildly excited, urging on both the great pitchers to continue their wonderful work,” Jack Ryder, Cincinnati Enquirer, May 3, 1917.

7 “I was sitting on the bench and happened to make a remark that we weren’t hitting Toney very much,” Vaughn told Baseball Magazine. “One of the fellows assented to this and then added that [the Reds] weren’t hitting me very much either. Then I recalled that they hadn’t made a safe hit off my delivery,” Baseball Magazine, July 1917.

8 “I didn’t fully realize it was a no-hit game until the ninth inning,” Toney explained later. “Then I took time to get my breath and my bearings and made up my mind to put all I had on whatever other balls I pitched.” Ibid.

9 “I had been putting a fastball over the plate for my first strike right along and put over one too many,” Vaughn explained. Ibid.

10 Rich Coberly, The No-Hit Hall of Fame: No-Hitters of the 20th Century (Newport Beach, California: Triple Play Publications, 1985), 48. “Cy scarcely had to move,” reported the Cincinnati Commercial Tribune, per Coberly’s book, “but if he had advanced two steps he could have taken it in front of his belt buckle. Instead, he had to catch it at his ankles, and he muffed the ball.”

11 Cincinnati Enquirer, May 3, 1917. The Commercial Tribune reported that Vaughn’s toss hit Wilson in the shoulder and that Kopf crashed into the catcher before he scored. Kopf himself told John Thorn that (in Thorn’s words) he “stopped dead in his tracks” when he saw Vaughn shovel the ball to Wilson and it was only after he realized that Wilson was frozen with confusion that he continued home to score. “Kopf, seeing Wilson standing there like a zombie as the ball rolled a few steps away, dashed home with the run,” wrote Thorn. See Coberly, 48, and https://ourgame.mlblogs.com/2012/02/04/.

12 Coberly.

Additional Stats

Cincinnati Reds 1

Chicago Cubs 0

10 innings

Weeghman Park

Chicago, IL

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.