May 24, 1940: Cleveland spoils Browns’ first night game in St. Louis

For nearly 15 minutes 25,562 excitedly impatient fans had been shouting and clapping their hands in unison. The claps turned to applause when St. Louis Mayor Bernard Dickmann finally emerged from the dugout, strode to a microphone behind home plate, and formally welcomed the crowd to the night’s special event.

Hosting chores were then turned over to St. Louis Browns’ President Don Barnes, who introduced a handful of dignitaries, including AL President Will Harridge. Finally, Kenesaw M. Landis, commissioner of baseball, was invited to press a button wired into the ballpark’s electrical system, and, to an audible gasp from the crowd, 764 1,500-watt bulbs on eight steel towers and 250 additional lights installed in the pavilion, bleachers, and other public areas burst into brilliance, illuminating every corner of Sportsman’s Park.

Less than one year earlier, Browns vice president and general manager Bill DeWitt had made clear the club’s opposition to introducing night baseball in St. Louis.

“Our main object right now,” said DeWitt, “is to get a winning ballclub. It’s next to impossible to sell a tailender to the public, nights or afternoons. I’m positive on that point. We’re tailenders now and I doubt that we’d increase our patronage at night in sufficient numbers to meet the cost of installing lights.”1

But the numbers from elsewhere in the major leagues were hard to ignore. While the Browns drew an average of 2,480 to 11 home games against the White Sox in 1939, the White Sox drew 30,000 in their one night game against the Browns in Chicago.2 In 11 games with the Indians in St. Louis, the average crowd numbered 1,050; the Browns played before 16,467 in one night game in Cleveland.3 Even the seventh-place Athletics could boast of hosting 120,000 fans for their seven night games in Philadelphia, nearly equaling the Browns’ total home attendance of 109,000 for the entire 1939 season.4

The basic plans required to install lights at Sportsman’s Park were already in hand. Blueprints had been drawn up in 1937, but a dispute over how the cost was to be split between the Browns and the Cardinals and which team would get to play the first game under the lights caused the project to be put aside.

Faced with the box-office numbers from around the league, resistance to night baseball within the financially strapped Browns organization crumbled, and on January 18, 1940, the club’s board of directors unanimously approved the installation of lights at Sportsman’s Park at a cost of $174,000,5 contingent on half of the tab being paid by the tenant St. Louis Cardinals. Cardinals owner Sam Breadon gave the project his approval the following day.

Estimates were that the construction of light towers and installation of lights would take less than four months. By agreement between the two clubs, the Browns would host the first night game, against the Indians on May 24, while the Cardinals would make their nighttime debut against the Brooklyn Dodgers on June 4. With only one minor setback – a wind and rain storm on May 14 that tore a light reflector from one of the towers, sending it crashing into the seats as spectators for a Browns-Yankees game, just postponed, were leaving the grandstand – the project was completed on schedule.

Devoted fans and the curious began to file into Sportsman’s Park on the evening of the 24th as early as 5:00 P.M. The lights were turned on at 7:45 to allow the Browns and the Indians to take fielding practice, after which the lights were extinguished in preparation for the scheduled ceremonies.

By game time, 24,827 cash customers and 735 pass-gate attendants filled the stands, the largest turnout for the Browns since a June 1928 game that brought Babe Ruth and the New York Yankees to town.

“It was carnival time in North St. Louis,” one observer said in describing the scene in and around the ballpark. “The neighborhood was lighted up like downtown, but the lights were brighter. Night baseball became a debutante in a bright, gleaming dress.

“Sportsman’s Park’s neighbors entered into the spirit of the occasion. They sat on their porches and watched the lights go on, and thrilled to the roar of the crowd that cheered the Browns and the Indians.”6

Starting that night for Browns was Elden Auker, winner of three of his first five decisions for the 11-15 club. Auker, a submarine hurler who had won 15 and 18 games for the 1934-1935 pennant-winning Detroit Tigers, had been acquired by St. Louis after an unhappy 9-10 season in Boston in which he had feuded on and off with Red Sox manager Joe Cronin.

Tapped for 18-10 Cleveland was 21-year-old fireballing sensation Bob Feller. Feller had galvanized the baseball world by tossing a 1-0 no-hitter against the White Sox on Opening Day, and owned a 5-2 record, a stingy 2.56 ERA, and 51 strikeouts in 59⅔ innings coming into the game.

Auker got off to a good start, retiring the Indians in order in the first inning. Feller, on the other hand, found himself in trouble right away, walking leadoff hitter Alan “Inky” Strange and allowing Walt Judnich to drive a pitch off the screen in right field for a double. After George McQuinn went down swinging, Rip Radcliff, hitting .391 overall and .477 over his last 10 games on his way to a .342 season, was given an intentional pass. With the bases now loaded, Feller fanned Chet Laabs on three straight pitches. But third baseman Ken Keltner booted a hard-hit grounder off the bat of Harlond Clift, and Strange sprinted home with the first run of the game.

Auker continued to make short work of the Indians, retiring three straight in the second and the first two hitters in the third before Feller, catching an outside curveball, drove the ball into the lower deck of the right-field pavilion, tying the game with his first major-league home run.

Cleveland snapped the tie in the fourth inning when Jeff Heath knocked a double off the wall in left-center and scored on a single to left by Rollie Hemsley. Rookie Ray Mack, who had been made the Tribe’s regular second baseman after brief stints with the club in 1938 and 1939, and who was pacing the club in the early going with a .340 average, looped a double to right, scoring Hemsley with an insurance run to make it 3-1.

The Browns managed only three more hits off Feller between the second and seventh innings, but broke through again in the eighth. McQuinn opened with a single to left before taking off on Radcliff’s third hit of the night, a double to left-center. Taking a wide turn around third, McQuinn collided with an Associated Press photographer but managed to untangle himself from the unlucky lensman and scattered camera parts to score without a play being made.

With Radcliff representing the tying run on second and one out, Laabs bunted up the third-base line. Feller pounced on the ball and tossed it to Keltner, who scrambled back to third to make the tag on a sliding Radcliff. Clift then flied to center, and Laabs was thrown out on an attempted steal of second, Hemsley to shortstop Lou Boudreau.

Auker disposed of the Indians in order in the ninth and Feller finished off the Browns in the same manner to end the game.

Feller struck out nine in going the distance, scattering seven hits and walking only two, for his sixth victory of what would be a career-high 27 for the season. Feller won the “triple crown” of pitching in 1940, leading the AL in wins, strikeouts, and ERA, as well as in games pitched, starts, complete games, shutouts, and innings pitched.

Auker took a hard-luck loss, hurling nine innings and surrendering nine hits and three runs while striking out six.

The outcome of the game may have been a disappointment to 25,000-plus Browns fans, but the reviews of the game under the lights were nonetheless excellent.

“After the Browns’ last batter had been retired,” the sports editor of the St. Louis Star-Times wrote the following day, “the huge crowd moved toward the exit gates, everyone voicing the sentiment of Mr. Baseball Fan of 1940 – that night baseball in the majors is here to stay.”7

This article appears in “Sportsman’s Park in St. Louis: Home of the Browns and Cardinals at Grand and Dodier” (SABR, 2017), edited by Gregory H. Wolf. Click here to read more articles from this book online.

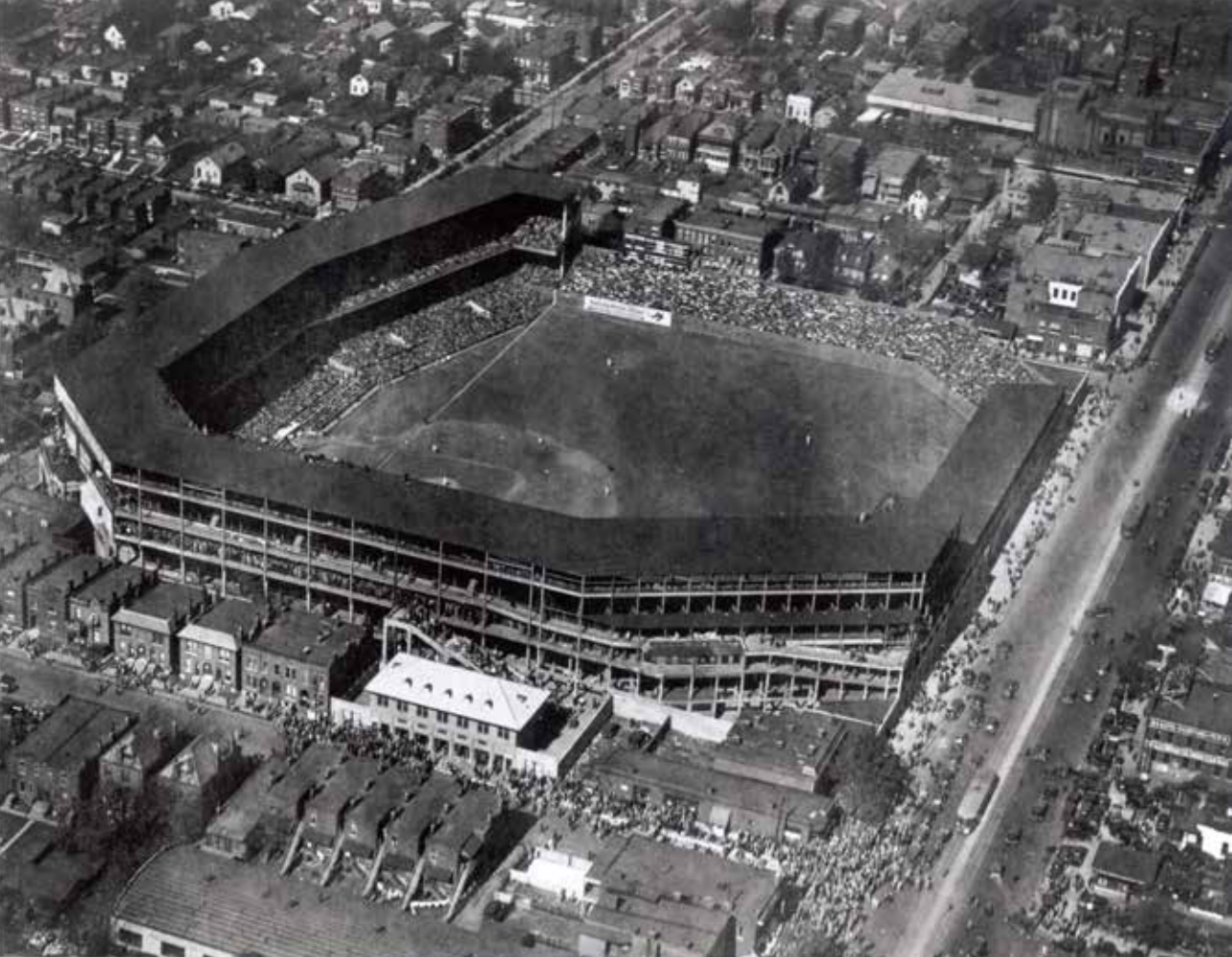

Photo Caption

Construction on Sportsman’s Park was finished in 1909. It served as the home park for the Browns until 1953 and for the Cardinals from July 1, 1920, until May 8, 1966. (National Baseball Hall of Fame, Cooperstown, New York)

Sources

In addition to the sources listed in the notes, the author also consulted:

Akron Beacon-Journal.

Cincinnati Enquirer.

Cleveland Plain Dealer.

Freeport (Illinois) Journal-Standard.

New York Times.

Sandusky (Ohio) Star-Journal.

The Sporting News.

Notes

1 Sid Keener, “Sid Keener’s Column,” St. Louis Star-Times, June 8, 1939: 30.

2 Sid Keener, “Sid Keener’s Column,” St Louis Star-Times, January 23, 1940: 16.

3 Ibid.

4 E.G. Brands, “St. Louis Greets Nocturnal Ball With Third Largest Attendance in the Browns’ History,” The Sporting News, May 30, 1940: 5.

5 Robert Morrison, “Sportsman’s Park to Have ‘Best Lighting in World,’” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, May 22, 1940: 14.

6 James Toomey, “North St. Louis Finds It Likes Night Baseball – Even Outside Park,” St. Louis Star-Times, May 25, 1940: 6.

7 Sid Keener, “Sid Keener’s Column,” St Louis Star-Times, May 25, 1940: 6.

Additional Stats

Cleveland Indians 3

St. Louis Browns 2

Sportsman’s Park

St. Louis

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.