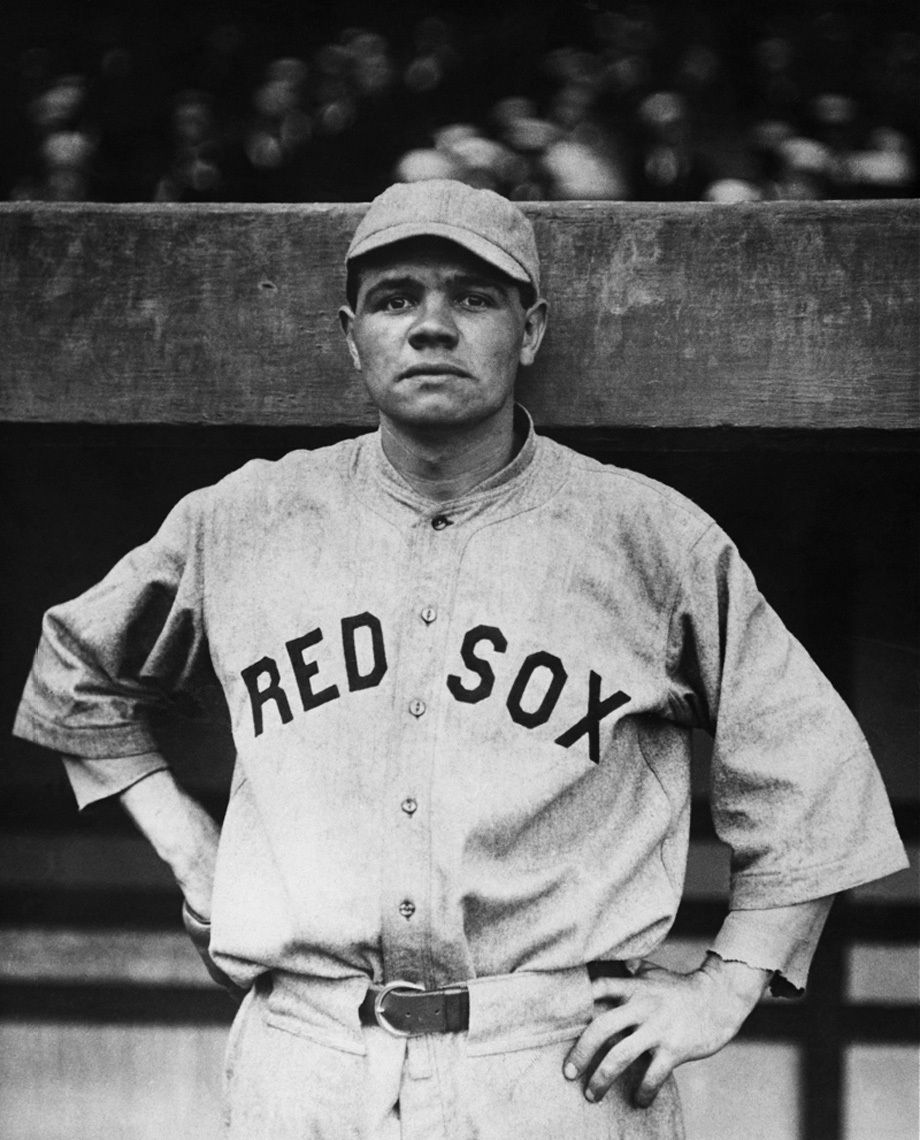

May 6, 1918: Boston’s Babe Ruth makes his first start as a position player

Boston Red Sox manager Ed Barrow scoffed at the very idea. Turn Babe Ruth, one of baseball’s top pitchers, into an everyday player? Just to let him hit some home runs and revel in the glory? Barrow imagined the wisecracks that would certainly follow. “I’d be the laughingstock of baseball if I changed the best lefthander in the game into an outfielder,” Barrow said early in the 1918 campaign.1

No one doubted that Ruth could handle his duties on the mound. He won 24 games in 1917 and led the American League with 35 complete games in 38 starts. One year earlier, the left-hander had won 23 times and topped the circuit in ERA (1.75) and shutouts (nine).

He also pummeled baseballs when he stepped into the batter’s box. In his rookie campaign of 1915, Ruth – besides posting an 18-8 won-lost record – knocked four home runs in just 92 at-bats. Braggo Roth topped the AL with seven homers. Roth, who split time with the Chicago White Sox and Cleveland Indians, went to bat 384 times. Babe hit three home runs in 1916 and two in 1917 over a combined 259 at-bats.

Barrow put Ruth at first base and right field during some spring-training games in 1918. Babe hit two home runs in one game against the Brooklyn Dodgers. He blasted five over the fence during batting practice when the same two teams met a few days later at Camp Pike, an Army post in Arkansas. The soldiers on hand enjoyed the show; Barrow did not. Baseballs cost money, and the Babe was losing them. Writers and fans came to expect these dynamic clouts. “Babe Ruth was not able to make any home runs,” a sportswriter noted after one game.2

The Red Sox began the regular season on April 15 at home against the Philadelphia Athletics. Ruth drew the Opening Day assignment and knocked a two-run single as Boston won, 7-1. He occasionally pinch-hit in the early going but did not play in the field except as a pitcher. Ruth hit his first home run of the campaign on May 4 in a 5-4 loss to the Yankees at the Polo Grounds. Ruth gave up all five runs. Even so, “Had all of Ruth’s mates played with the same vigor in all departments, especially hitting, that he did, the Sox would have triumphed. Babe’s hitting was really the feature of the game. He walloped a homer into upper tier of the grandstand in the seventh inning when (Everett) Scott was roosting on first.”3

Two days later, on May 6, 1918, again against the Yankees, Barrow penciled in Ruth’s name at first base. The regular at that position for Boston, Dick Hoblitzell, had fallen into a dreadful slump and injured a finger. Barrow, at least for now, could forget all that “laughingstock” business.

Babe had never started a regular-season game at any position except pitcher. Barrow put him in the sixth spot in the batting order. The Red Sox’ record stood at 12-5 going into the contest; the Yankees’ at 8-8. Boston’s submarine-style right-hander Carl Mays faced New York lefty George Mogridge.

Boston broke out on top with three runs in the fourth. Wally Schang led off with a double but was thrown out at third after Stuffy McInnis laid down a “pretty bunt, leaving practically no opportunity for a play at first.”4 That brought up Ruth, “the sensational hitting pitcher for the Bostons,”5 who blasted a two-run homer into the right-field stands. W.C. Macbeth in the New York Tribune, wrote that Ruth “lined one into the upper right tier some fifty feet fair, that shot on a line like a rifle bullet sand knocked the back out of the seat.”6 Yankees owner Jake Ruppert and Red Sox owner Harry Frazee were seated together at the game. Ruppert offered $150,000 for Ruth just moments after the round-tripper sailed over the fence. It was a joke, and the two men laughed.7 Scott followed Ruth by rattling a double off the left-field wall. He raced home on Sam Agnew’s single to make the score 3-0.

New York tied the game in the bottom half of the frame “because of a lot of bush league errors that completely unnerved Carl Mays.”8 Home Run Baker (acquired from Philadelphia before the 1916 season) led off with a base hit, and Pratt drew a walk. Wally Pipp’s single loaded the bases. Ping Bodie “whistled”9 a hit to left that scored Baker, while Schang uncorked a wild throw that brought home Pratt. An error by Agnew allowed Pipp to score.

The Yankees added three more runs in the fifth. Roger Peckinpaugh singled, and then Harry Hooper muffed a flyball off the bat of Baker. Pipp reached base on a wild pitch that scored Peckinpaugh. Bodie singled to bring home Baker and Pipp. That ended the day for Mays, who gave up six runs. Just two were earned. Sad Sam Jones entered the game and got the final two outs of the inning.

Following a scoreless sixth, New York put up another three-spot in the seventh. Baker and Truck Hannah singled. Pipp and Bodie followed with doubles. The Yankees added a solo run in the eighth to make the final score 10-3. Pipp, Bodie, and Baker each had three hits in the game. Bodie drove in five runs.

Mogridge, meanwhile, gave up only the three runs in the fourth. He scattered 10 hits and improved his won-lost record to 4-1, while Mays fell to 3-2. Besides hitting a home run, Ruth added a single and went 2-for-4. He raised his batting average to a robust .450. Already, some newspaper writers were suggesting that pitchers surrender to Ruth’s powerful swing. “The best way to keep Babe Ruth from breaking up a ball game is to walk him and take a chance on the next batsman,” wrote the Paterson (New Jersey) Morning Call.10 Another writer put it this way: “As a rule, a pitcher at bat holds little interest for the fans, but when Babe Ruth steps to the plate the crowd is disappointed if the Red Sox twirler doesn’t hit the ball a mile.”11

The next day, in a 7-2 loss to the Washington Senators, first baseman Ruth hit another homer, his third in three games. A Boston Globe writer acknowledged that “Ruth’s big ambition is to be an everyday member of the ball club.”12 Even so, while the Red Sox could use Babe’s bat, “it’s not likely that Barrow will use Ruth except as an emergency regular, but the Babe’s work yesterday suggests that the future holds much in store for him.”13 Barrow still envisioned Ruth as a pitcher. He and his phenom went ’round and ’round. Sometimes, Ruth begged off his mound duties. He complained that his wrist hurt too much to pitch. Barrow didn’t believe him. All the while, Ruth insisted “I like to pitch.”14

“My main objection is that pitching keeps you out of so many games,” Ruth continued. “I like to be in there every day.” Given a choice, Ruth wanted to play only first base. No one gave him that choice. “I don’t think a man can pitch in his regular turn, and play some other positions and keep the pace year after year,” he said. “I can do it this season all right. I’m young and strong and don’t mind the work, but I wouldn’t guarantee to do it for many seasons.”15

Ruth excelled while doing double duty in 1918, a season cut short due to America’s entry into World War I. He appeared in 95 games, 20 of them as a pitcher. The 23-year-old finished with a 13-7 won-lost record and a 2.22 ERA. In the other contests, he pinch-hit, played first base, or saw action in the outfield. Babe hit 11 home runs, “despite the soggy ball,”16 and tied for the league lead with the Athletics’ Tillie Walker. The Red Sox won the World Series against the Chicago Cubs. Ruth hit just .200 (1-for-5) and failed to go deep. On the mound, he went 2-0 in two starts with a 1.06 ERA.

After the season columnist W.G. Evans asked, “Who was the sensation of 1918 in major league circles?” This was a year when Ty Cobb batted .382 and Walter Johnson posted a 1.27 ERA. “My answer without hesitation,” Evans wrote, “would be ‘Babe’ Ruth of the Boson Red Sox.” Ruth was, according to Evans, “a great pitcher,” but – maybe – an even more talented batsman. “He always was dangerous at the bat in season’s [sic] past,” Evans wrote, “but not until 1918 did Babe Ruth realize that he was a great slugger.”17

Notes

1 Robert Creamer, Babe: The Legend Comes to Life (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1974), 152.

2 Creamer, 151.

3 “Babe’s Hitting All Right, but Yanks Bunch on Him,” Boston Globe, May 5, 1918: 15.

4 W.J. Macbeth, “Ping Bodie Brings Glory to Yankee Escutcheon,” New York Tribune, May 7, 1918.

5 Frederick G. Lieb, “Murderers’ Row Batters Red Sox,” New York Herald, May 7, 1918: 13.

6 Macbeth.

7 Leigh Montville, The Big Bam: The Life and Times of Babe Ruth (New York: Doubleday, 2006), 69.

8 Macbeth.

9 Ibid.

10 “Baseball Gossip from Major Leagues,” Paterson (New Jersey) Morning Call, May 7, 1918: 3.

11 “Baseball Gossip,” Wichita Daily Eagle, May 7, 1918: 7.

12 “Live Tips and Topics.” Boston Globe, May 7, 1918: 3.

13 Ibid.

14 Montville, 74.

15 Ibid.

16 Babe Ruth and Bob Considine, The Babe Ruth Story (New York: Signet, 1992), 51.

17 W.G. Evans, “Babe Ruth Is Great Sensation of Year in Major Leagues,” Lincoln (Nebraska) Star, November 17, 1918: 7.

Additional Stats

New York Yankees 10

Boston Red Sox 3

Polo Grounds

New York, NY

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.