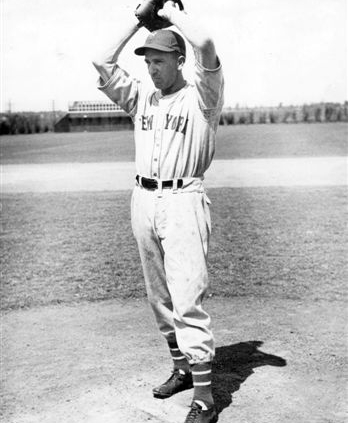

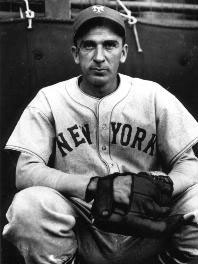

May 8, 1929: Carl Hubbell tosses no-hitter in 18th career start

Not yet known as “King Carl” or “Meal Ticket,” the New York Giants’ Carl Hubbell tossed the first and only no-hitter in his 16-year big-league career in just his 18th start, defeating the Pittsburgh Pirates, 11-0, on May 8, 1929. Hubbell joined “that lofty gallery in baseball’s hall of fame,” gushed sportswriter William E. Brandt in the New York Times, “where the mural decorations are restricted to the deep-graven names of no-hit pitchers.”1 Despite the lopsided score, the game produced several dramatic and tense moments in the final, history-making frame, leading to some confusion about Hubbell’s feat.

Not yet known as “King Carl” or “Meal Ticket,” the New York Giants’ Carl Hubbell tossed the first and only no-hitter in his 16-year big-league career in just his 18th start, defeating the Pittsburgh Pirates, 11-0, on May 8, 1929. Hubbell joined “that lofty gallery in baseball’s hall of fame,” gushed sportswriter William E. Brandt in the New York Times, “where the mural decorations are restricted to the deep-graven names of no-hit pitchers.”1 Despite the lopsided score, the game produced several dramatic and tense moments in the final, history-making frame, leading to some confusion about Hubbell’s feat.

Coming off a second-place finish in 1928, just two games behind the St. Louis Cardinals, the Giants were once again expected to challenge for the NL pennant. But skipper John McGraw’s club had not played like contenders thus far. After losing the first contest of their three-game series to the Pirates as part of an 11-game homestand, the Giants (5-7) were in a tie for fifth place, 3½ games behind the upstart Boston Braves. Furthermore, “Little Napoleon” was under the weather, and for the second straight game was unable to join the club he had guided since 1902. He was replaced by trusted player-coach Ray Schalk.2 The Pirates, too, had pennant aspirations, and were in fourth place (7-7). Manager Donie Bush’s squad could lay a legitimate claim to the best-hitting club, from the first to eighth spot, in the league, with six starters who eventually batted in excess of .300 in 1929.

Toeing the rubber for the Pirates was 33-year-old left-hander Jesse Petty, acquired from the Brooklyn Robins in the offseason, along with Harry Riconda, for shortstop Glenn Wright. He had a record of 55-61 in parts of six campaigns, including 1-2 (4.95 ERA) so far in ’29. Hubbell, a skinny, 6-foot, 170-pound 26-year-old left-handed screwballer, had debuted the previous July, going 10-6 and posting a 2.83 ERA in 124 innings in just over two months of action. Hubbell, Larry Benton (25-9), and Freddie Fitzsimmons (20-9) had formed the most impressive pitching trio in the league. Hit hard in his last start (seven runs in 7⅓ innings at St. Louis), Hubbell (2-0 and 4.26 ERA) was still acclimating himself to the big leagues.

With temperatures hovering in the 50s on a cool, damp spring day, about 8,000 spectators showed up at the Polo Grounds for a midweek ballgame. The Pirates’ Sparky Adams led off the game with a sharply hit grounder to shortstop Travis Jackson, who threw wildly to first, enabling Adams to reach second standing up. After Lloyd Waner sacrificed Adams to third, Hubbell defused the threat by retiring the Bucs’ two most formidable hitters, Paul Waner and Pie Traynor. With “bewildering speed” and impeccable control, Hubbell cruised for the next seven innings, retiring every batter, save for a two-out walk to Adams in the third.3

The Bucs “made the wrong guess with Petty,” opined sportswriter Edward F. Ballinger of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.4 Petty would have set down the side in order in the first had not third sacker Traynor thrown low to first on Freddie Lindstrom’s two-out grounder for a crucial error. Mel Ott, the 21-year-old left-handed slugger, who had not played the previous two games, both against southpaws, smashed a fly to deep right-center, just out of the reach of Paul Waner, who leaped, but could not catch the ball, which bounced off a seat and back into the field of play for a two-run homer. Left fielder George Grantham “robbed” Bill Terry of an extra-base hit with a leaping catch at the wall to end the inning.5

The Giants’ barrage continued in the next two innings. Rookie Chick Fullis blasted a one-out home run, his third in his third full game, just inside the left-field foul pole into the second tier of the grandstand. Bob O’Farrell’s triple to deep right sent Petty to the showers. Hubbell greeted reliever Fred Fussell with a fly ball to deep right to drive in O’Farrell for the Giants’ fourth run. Andy Cohen led off the third with his second home run in two games. Fullis’s two-out single, driving in Ott, who had walked, gave the Giants a seemingly insurmountable 6-0 lead.

Ray Kremer, one of the NL’s most consistent starters since his debut in 1924, was thrust into the unceremonious role as cleanup artist and quieted the Giants in the fourth and fifth innings, before being attacked “savagely” in the sixth.6 O’Farrell opened the onslaught with a one-out double, and moved to third when first baseman Earl Sheely fumbled Hubbell’s grounder. Both scored on Edd Roush’s triple. Cohen’s single scored Roush. The Pirates bullpen remained silent; Kremer was in to take one for the team. The scoring concluded with Ott’s towering, NL-leading sixth home run, which landed in “his private shooting gallery upstairs in right field” (according to the New York Times), for an 11-0 Giants lead.7

“Hubbell’s mastery was visible in the absence of any sensational fielding feats,” wrote Brandt in the Times, but all of that changed when the hurler faced what the sportswriter called his “real test” in the final inning.8 Riconda, pinch-hitting for Kremer, lofted to short left what Harold C. Burr of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle called “an undeserving yet ruinous Texas Leaguer.”9 Fullis, making a mad dash, reached for the ball with both hands, according to the Times, but fumbled it for an error.10 Fullis was “perhaps more excited in the pinch than the pitcher,” wrote Brandt.11 The next batter, Sparky Adams, hit a tailor-made routine double-play grounder, but Jackson muffed it for his second error of the game. Seemingly unaffected by his teammates’ miscues, Hubbell fanned Lloyd Waner looking with a devastating curve.

To the plate stepped Little Poison’s brother, Paul “Big Poison” Waner, the 1927 NL batting champion (.380) and MVP, who had entered the game in an uncharacteristic slump, batting just .262. Hubbell faced his “biggest moment of the day, perhaps in his whole life,” wrote Brandt in the kind of hyperbole reserved only for the greatest of achievements.12 Waner hit a high chopper to the right side of Hubbell, whose one “fielding weakness” according to the Times, was this type of comebacker.13 But on a day when everything seemed to go right for the Giants, so too did Hubbell’s fielding. Diving for the ball, Hubbell “whirl[ed] and without waiting to recover balance he fired the ball to second.”14 Jackson caught the ball cleanly and rifled a strike to Bill Terry at first to complete the game in just 1 hour and 35 minutes.

Like the rest of his teammates, Hubbell scampered off the field, apparently unaware of his feat. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle reported that the “outfield grass was strangely devoid of converging youths … straining every muscle to slap the departing athletes on the back.”15 The remaining crowd was eerily silent while a large group of fans gathered in front of the press box inquiring about the official scoring. Gradually word reached the field that Riconda’s fly to left was ruled an error, and not a hit. At the time, the scoreboard in the Polo Grounds did not show hits and errors, just the inning-by-inning and cumulative scoring. Hubbell was already in the Giants’ clubhouse when he learned that he had tossed a no-hitter. “Schalk’s just told me it’s true,” said Hubbell ecstatically.16

Hubbell’s performance “testified to his unshakeable nerve in the critical inning,” wrote Brandt.17 Hubbell struck out four and walked one while facing 28 batters. It was the first no-hitter in the majors since the Chicago White Sox’ Ted Lyons defeated the Boston Red Sox on August 21, 1926, and the Giants’ first since Jesse Barnes turned the trick against the Philadelphia Phillies on May 7, 1922. “Carl mixed ’em up a great assortment,” said Hubbell’s batterymate, Bob O’Farrell. “Screwballs, fastballs, and curves.”18The Pirates pounded Hubbell’s screwball into the dirt all afternoon, and managed only five outfield fly outs.

The Giants blasted a trio of hurlers for 12 hits, including seven extra-base hits, of which four were round-trippers. Mel Ott, the offensive star of the game with two homers, three runs scored, and four RBIs, improved his batting average to .405 with a major-league-best .911 slugging percentage.

Hubbell was honored by the Giants before their game with the Chicago Cubs on May 12. Team president Charles Stoneham presented him with a commemorative watch.19 While the NL set a record by averaging 10.8 runs per game during the offensive explosion of 1929, Hubbell emerged as the ace of the Giants’ staff and the best southpaw in the league. He finished with an 18-11 record and 3.69 ERA in 268 innings. Hubbell went on to win 253 games, 36 of those by shutout, but never flirted seriously with another no-hitter.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also used Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, the SABR Minor Leagues Database (accessed through Baseball-Reference.com), and The Sporting News archive via Paper of Record (accessed through SABR.org).

Notes

1 William E. Brandt, “No Hits Off Hubbell, as Giants Win,” New York Times, May 9, 1929: 32.

2 William J. Chipman, Associated Press, “Yankees’ Sluggers Go to Top of American League,” News Journal (Wilmington, DE), May 8, 1929: 18.

3 Edward F. Ballinger, “Bucs Held Hitless, Runless, by Hubbell,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, May 9, 1929: 18.

4 Ballinger.

5 “Here’s the Complete Story, Folks – By Mr. Hubbell,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, May 9, 1929, 1929: 21.

6 Ballinger.

7 Brandt.

8 Ibid.

9 Harold C. Burr, “Hubbell Did Not Know He Hurled No Hit Game Until Jackson Told Him,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, May 9, 1929: 32.

10 Brandt.

11 Ibid.

12 Ibid.

13 Ibid.

14 Ibid.

15 Burr.

16 Ibid.

17 Brandt.

18 Burr.

19 William E. Brandt, “Benton Blanks Cubs With Two Hits,” New York Times, May 12, 1929: S1.

Additional Stats

New York Giants 11

Pittsburgh Pirates 0

Polo Grounds

New York, NY

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.