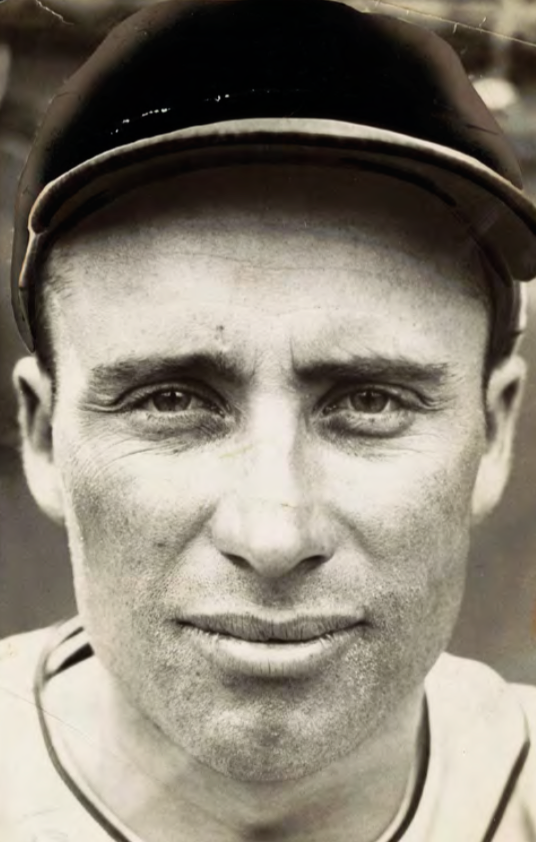

October 1, 1933: Wally Berger’s $10,000 home run

It didn’t have nearly the impact of Bobby Thomson’s pennant-winning home run or the World Series-winning blasts of Bill Mazeroski and Joe Carter, but for the perennially weak Boston Braves of the 1920s and ’30s, Wally Berger’s pinch-hit grand slam on the final day of the 1933 season was worthy of bold-face headlines and its own nickname: “The $10,000 homer.”

It didn’t have nearly the impact of Bobby Thomson’s pennant-winning home run or the World Series-winning blasts of Bill Mazeroski and Joe Carter, but for the perennially weak Boston Braves of the 1920s and ’30s, Wally Berger’s pinch-hit grand slam on the final day of the 1933 season was worthy of bold-face headlines and its own nickname: “The $10,000 homer.”

The monetary significance was a sign of the times. While “finishing in the first division” is not a term familiar to most baseball fans born in the era of four- and six-division baseball, for many years this goal was an important one for major-league teams. Before the American and National Leagues were broken into East and West divisions in 1969, clubs finishing in the first division – the upper half (or top five) of the 10-team AL and NL – received a portion of the “Players Pool” money funded by gate receipts of that year’s World Series. From 1901 to 1960, when both leagues had eight teams, the upper half corresponded to the top four clubs in each circuit.

Logically, the higher you finished in the first division, the greater a percentage of the World Series loot your team collected. Since players then almost all had offseason jobs to make ends meet, this extra cash meant a lot – and thus the difference between fourth and fifth place did as well. Strong teams like the Yankees and Cardinals routinely got a piece of the pie, but from 1922 to 1932 the Braves received nether a sliver with 11 consecutive seasons in fifth place or lower.1

In 1933, however, Boston made a spirited late-season run not only for the first division, but for the NL championship. Under .500 as late as July 30, the Tribe used a 22-6 August to climb to second place heading into a huge six-game series at home against the league-leading New York Giants. Nearly 160,000 fans packed Braves Field for the contests – more than one quarter of the team’s total attendance for their 77 home dates – but the Giants won four of five (with one tie) to drop Boston nine games back.

That started a tailspin that soon had the Braves in fifth place, and a bout of pneumonia that knocked their leading hitter (Berger) out of the lineup for three weeks down the stretch kept them from rebounding. Boston remained in fifth heading into the season finale at Braves Field against the Philadelphia Phillies on October 1, and although a still-weak Berger had emerged from a Pittsburgh hospital bed to rejoin the club, he was in street clothes on the bench at game’s start.

Berger, however, was itching to get back into uniform. The starting pitcher for Philadelphia was Reggie Grabowski; two weeks before, after being discharged from the hospital, Berger had spent his last afternoon in Pittsburgh watching the young right-hander pitch a complete game against the Pirates at Forbes Field. “I sat right behind home plate to see what kind of stuff he had,” Berger told author and SABR member Richard “Dick” Beverage during a July 1988 video interview, conducted five months before Berger died at 83. “I saw a little curve and I said, ‘Yup, that’s what he’s got.’”2

The slugger-turned-spectator stored away the knowledge, and looked forward to hitting against Grabowski in the future. He assumed that would be next season, but suddenly the future was now. Boston was just a half-game behind the fourth-place St. Louis Cardinals, and a Braves win coupled with a Cardinals loss to the Chicago Cubs would clinch fourth place – and the first-division money that came with it – for Boston. Braves manager Bill McKechnie likely would not have thought of letting Berger play if this were not the case, but in the fourth inning he allowed his slugger to suit up. Berger, after all, had 26 of the team’s 53 home runs and 102 of its 507 RBIs to go along with his .311 batting average, and a fourth-place finish would mean hundreds of dollars for each player – a good chunk of the average major leaguer’s salary at the time – as well as a hefty $5,000 bonus for McKechnie.

While the manager waited for the perfect opportunity to get Berger in, the game stayed tight most of the day. The Phillies scored a run in the third off Braves starter Ed Brandt, and still led 1-0 behind Grabowski heading into the bottom of the seventh. Boston started the frame strong, as Baxter Jordan and Randy Moore both singled, but Pinkey Whitney struck out and Hal Lee grounded to first, advancing the runners to second and third. Grabowski now intentionally walked catcher Shanty Hogan, a logical move in that it set up an out at any base and brought shortstop Walter “Rabbit” Maranville to the plate.

Maranville was a .218 hitter near the end of his Hall of Fame career, and McKechnie figured this might be his best chance to use Berger. He called Rabbit back, sent Berger up to pinch-hit, and put Ben Cantwell in at first base to run for Hogan. Berger’s broad back flashed his familiar number 3 as he carried several bats to the plate, and then flung all but one aside. “They came out to talk with him [Grabowski],” Berger told Beverage, “and I just know he’s going to come in with that dinky little curve.”

Berger swung and missed on Grabowski’s first pitch, losing his grip and sending his bat flying, but managed to work the count to 2-and-2. Then, according to Gerry Hern of the Boston Post, Grabowski “tried to push an inside pitch through the slot for the third strike”3 and Berger met the anticipated dinky little curve dead on. The ball sailed into the left-field stands for a grand slam, and the crowd and bench erupted. Maranville greeted the still-sick hero at home plate with a hug and a kiss on each cheek, and the rest of the team joined in the on-field celebration – a very unusual scene in this era for a game not yet completed. “It certainly was the most dramatic incident seen in a game in Boston in years,” wrote James O’Leary in the Boston Globe, “and the tumult lasted for five minutes or more.”4

That was it for the Braves offense, but it was enough. Bob Smith, who had come on in relief in the sixth when Brandt hurt his leg fielding a bunt, held Philadelphia scoreless the rest of the way. The Cardinals still had to lose for fourth place to be Boston’s, so many of the 4,000 fans at Braves Field stayed in the ballpark until news of the final score (7-1, Cubs) came in from St. Louis. The reaction by the crowd, especially since there would be no postseason games coming for the home club, underscored just how lean a period the previous 15 years had been for Hub baseball fans saddled with awful Braves and Red Sox teams.

Along with the pride that came with helping the club to its best record (83-71) in 12 years, each Braves player now also knew he had a check coming. Front-page headlines the next day in Boston’s several daily newspapers varied in predicting exactly how much the homer would be worth in bonus money, since the total amount was predicated on attendance in the World Series yet to be played. The Post called it “the $10,000 HOMER,” the Boston Herald deemed it a “$15,000 HOME RUN,” and the Globe noted it worthy of “$10,000 of Series Spoils.” In the end, it would actually be worth $7,100 to the players – or $242.82 for each – along with $5,000 for future Hall of Fame skipper McKechnie out of the Braves’ coffers.

Over the years, the aura around Berger’s blast grew. Later accounts claimed that he had announced to McKechnie in front of the entire dugout earlier in the game that he wanted just one at-bat against Grabowski. “If he throws that curveball over the plate,” Berger supposedly stated, “I’ll hit it out of the park.”5 He never mentioned such a boast in his interview with Beverage, but Berger clearly delighted in retelling the story.

So did the guy whom Berger’s shot hurt the most. The Braves would later field better teams in Boston than this one, including the 1948 National League champions. But for Judge Emil Fuchs, who owned the Braves from 1923 to 1935, the ’33 finale would remain his favorite all-time game – albeit an expensive one. “One of the biggest thrills I ever got out of baseball cost the Braves $5,000, but I always regarded it as well worth it,” Fuchs later wrote in one of a series of guest columns he did for the Globe, referring to the bonus he paid his manager. “I recall having a hat and cane. The first thing I knew [when Berger homered] both were flying high in the air. I tossed them as high as I could. I never paid out $5,000 more readily or received so much happiness than when I gave that check to Bill!”6

Sources

In addition to the sources mentioned in the Notes, box scores for this game can be seen on baseball-reference.com, and retrosheet.org.

http://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/BSN/BSN193310010.shtml

http://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1933/B10010BSN1933.htm

Beverage, Dick. Video interview with Wally Berger at Berger’s Redondo Beach, California, home, July 27, 1988.

Boston Globe, “Babe Ruth and Berger Heroes on Final Day,” October 2, 1933.

Boston Herald, “Berger Wallops $15,000 Home Run With Bases Full,” October 2, 1933.

Boston Post, “Berger Slams $10,000 Homer,” October 2, 1933.

Caruso, Gary. The Braves Encyclopedia (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1995).

Fuchs, Judge Emil. “Berger ‘Earns’ $5000 for Boss,” Boston Globe, December 22, 1942.

Kaese, Harold. The Boston Braves (New York: Putnam Press, 1948).

Klapisch, Bob, and Pete Van Wieren. The World Champion Braves: 125 Years of America’s Team (Atlanta: Turner Publishing, 1995).

Notes

1 According to Robert S. Fuchs (the Judge’s son) and Wayne Soini in Judge Fuchs and the Boston Braves, the players had an additional incentive for striving for the players’ pool money. “Everyone on the team, including the owner, the Judge, took a pay cut in 1933 down 10 or 20 percent. Berger dropped from $10,000 to $9,000. The cuts, justified or not, were inflicted with the stated proposition that they would be made up for if attendance at Braves Field in 1933 was as good as 1932. It was not, but the Judge wrote Berger before the end of August: ‘I believe your spirit and the spirit of the club has done so much for Boston and the Braves that irrespective of whether or not [the 1932 level] is reached, I feel it is justly due to you for me to reinstate the amount of your 1932 contract, and you will receive the proportionate amount of your cut in your salary check on the various pay days left this year. The first check to have the added share will be your salary check of September 1st.” (See Robert S. Fuchs and Wayne Soini, Judge Fuchs and the Boston Braves, 1923-1935 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., Inc., 1998), 100. According to the authors, Berger constantly felt that he was being underpaid and engaged management accordingly in negotiations. “In 1933, when everybody was taking cuts, he argued that he had expected a raise: ‘I will sign for the same salary as last year and consider that I have received a pay cut.’” Correspondence relating to these negotiations can be found in Appendix B of the book at 139-152.

2 Dick Beverage video interview with Wally Berger at Berger’s Redondo Beach, California, home, July 27, 1988.

3 Gerry Hern, “Berger Slams $10,000 Homer,” Boston Post, October 2, 1933.

4 James O’Leary, “Babe Ruth and Berger Heroes on Final Day,” Boston Globe, October 2, 1933. Former Knot Hole Gang member Philip Gates retained his membership card into adulthood as one of his most prized possessions. Fuchs and Soini wrote, “With the card and a nickel, a Knot Hole Gang member would have a seat over in the third base pavilion near left field, where the bullpen crews warmed up before and during the games. The cards were passports for thousands of youngsters at a time of tight family budgets. For one nickel Philip Gates saw something he remembered the rest of his life. ‘I remember Wally Berger,’ he said, ‘hitting the grand slam in the final game of the 1933 season, which lifted the Braves into the First Division! Unheard of heights!’” Fuchs and Soini, 92.

5 Harold Kaese, The Boston Braves (New York: Putnam Press, 1948, republished by Northeastern University Press, 2004), 222-223.

6 Judge Emil Fuchs, “Berger ‘Earns’ $5000 for Boss,” Boston Globe, December 22, 1942. Fuchs recalled, “I was sitting in the bleachers with Sidney Rabb, who headed the Stop & Shop supermarket chain. Sidney was not only a stockholder of the Braves but a close personal friend. In the last part of the game, the Braves were behind. With bases loaded, McKechnie called upon Wally Berger. Berger, though one of our great hitters, had had a severe cold but that day put on his uniform and an overcoat, suffering from a fever with a temperature of 102. Nonetheless, he took the first pitch and hit it into the bleachers for a home run. I was among many who cheered without restraint, taking my cane and hat and waving them around with enthusiasm. Afterward, Sidney said to me, ‘Judge, you are a baseball fan but a bad business man. Don’t you know that hit will cost you $5,000?’ He knew, of course, about a clause in our contract with McKechnie, providing him with a nice bonus if the team finished in the first division.” Fuchs and Soini, 87-88.

Additional Stats

Boston Braves 4

Philadelphia Phillies 1

Braves Field

Boston, MA

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.