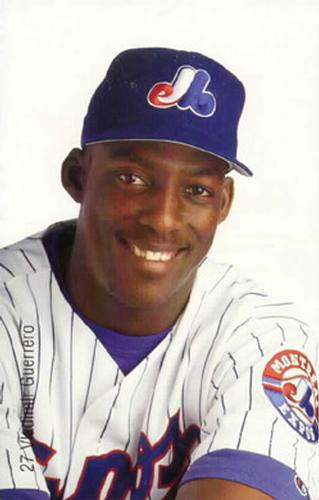

October 2, 1999: Vlad Guerrero impales his 40th home run of season

He was nicknamed Vlad the Impaler, and while he isn’t a bad guy — his 15th-century namesake, on the other hand, came by his nickname honestly — Vladimir Guerrero did some pretty mean things to baseballs thrown by National and American League pitchers during his playing career.

He was nicknamed Vlad the Impaler, and while he isn’t a bad guy — his 15th-century namesake, on the other hand, came by his nickname honestly — Vladimir Guerrero did some pretty mean things to baseballs thrown by National and American League pitchers during his playing career.

The Expos were going through a terrible period in 1999, as they were completing the second of four straight seasons of 90 or more losses. Management had sold off the stars who made the team so promising earlier in the decade, but the farm system could still produce a gem like Guerrero. He was a five-tool player when he came up to the Expos for good in 1997 (he had 27 plate appearances in 1996). He had power, hit for average, and ran like a deer. And on October 2, 1999, he became the first Expo to hit 40 home runs in a season as the Expos pasted the Phillies 13-3.

“He’s in a league all his own,” said teammate Trace Coquillette. “If there was a league better than this league, he’d be in it.”1

Prior to Guerrero’s arrival in Montreal, no member of Nos Amours had hit 40 home runs in a season.2 Guerrero set a new mark in 1998 with 38, breaking the record of 36 set by Henry Rodriguez in 1996, and he surpassed his own record when he hit number 39 on October 1 off the Phillies’ Mike Grace in a 7-4 Expos win.

If Guerrero could have chosen the team he wanted to face to try for his 40th home run, it might very well have been the Phillies because their pitching staff was awful, and a major reason why the team ended up with a 77-85 record in 1999. They were 13th out of 16 teams in the league in both team ERA (4.92) and home runs allowed (212). Guerrero was known for loving his mother’s home cooking. The Phillies’ pitching staff made his mouth water almost as much.

Paul Byrd started for Philadelphia. His last name was appropriate because many of his pitches took off on long flights. Despite a 15-10 record going into the game, he had a 4.60 ERA and he was third in the National League in home runs allowed with a whopping 31. Byrd had gone seven innings and given up two earned runs in his last start for the victory in a 3-2 win over the New York Mets. Jeremy Powell (3-8) started for Montreal, having given up eight earned runs in 5⅔ innings of a 10-0 Expos loss to the Braves.

Maybe Byrd was having sympathy pains over his opponent’s previous start because from the get-go he seemed intent on duplicating Powell’s pitching line from that game. Byrd began by walking leadoff hitter Rondell White, but got the next batter, Peter Bergeron, to hit into a fielder’s choice that forced White at second. Bergeron himself moved to second on a wild pitch, then to third when Michael Barrett singled to deep short. This brought up Guerrero, as free a swinger as ever batted in the majors. He took Byrd’s first pitch and deposited it deep in the left-field stands for milestone home run number 40. The next batter, Fernando Seguignol, proved to be a more patient hitter than Guerrero; he let one pitch go by for a ball before blasting a home run to right-center field. The Expos led 4-0 after one.

Philadelphia got one back in the bottom of the first, when Mike Lieberthal doubled to drive home Bobby Abreu, who had singled, but the Expos blew it open in the top of the second. Powell led off by hitting the first of his two career doubles, followed by White’s second consecutive free pass. Bergeron attempted to sacrifice the runners ahead by bunting to third, and Byrd misplayed the throw for an error that brought Powell home. Barrett walked to load the bases. Byrd seemed poised to get out of the jam when Guerrero flied out and Seguignol struck out, but the next batter-–this is the City of Brotherly Love, remember–-was Vladimir’s older brother Wilton, and he drove Byrd’s second pitch into the right-field bleachers for a grand slam to give the Expos a 9-1 lead. This marked the second time the Guerrero brothers homered in the same game; they had done it on August 15, 1998 at Cincinnati.

Powell was probably pinching himself as he took the mound for the top of the third, because he was not used to an eight-run lead; his average run support in 1999 was 4.26 runs per game. A young pitcher like Powell, who was 23 at the time, often lets up with such a cushion, especially if he’s making his last start of the season. Powell may have let his concentration sag a bit in the bottom of the second, when some sloppy pitching led to two runs. With one out, he walked Marlon Anderson, then hit number-eight hitter Alex Arias with a pitch on a 2-and-2 count. Chad Ogea, who had replaced Byrd in the top of the inning, bunted the runners ahead, and they both scored when Doug Glanville hit a line-drive single to left to make the score 9-3. Powell got a strikeout of Ron Gant to end the inning, and probably a stern talking-to from Expos manager Felipe Alou when he returned to the dugout. Whatever happened, Powell didn’t give up any more runs and finished with three earned runs allowed over six innings in what turned out to be the last win of his major-league career. His success that night could be attributed, in part, to listening to his batterymate, Barrett.

“I wanted to throw more breaking balls, but he [Barrett] said to stay aggressive, stay with the fastball until I got ahead in the count, then use the breaking ball,” said Powell. “It worked.”3

The same can’t be said for Philadelphia pitcher AmauryTelemaco. After a 1-2-3 inning when he took over in the fifth, he didn’t quit while he was ahead, choosing instead to come out for the sixth. He started off well enough by striking out White, but gave up back-to-back singles to Bergeron and Barrett, which brought Guerrero up again. Maybe Guerrero had a train to catch because he swung on the first pitch again and launched it over the right-field fence for his 41st home run of the year and second three-run blast of the game. Take that, big brother.

Miguel Batista came on in the seventh and went the rest of the way to record his first major-league save, and was happy with the achievement. “Now I’ve got it all — a save, short relief, long relief, and a few starts,” he said. “Now I can truly say I’m a complete right-handed utility pitcher.”4

Montreal decided that 12 wasn’t enough in the eighth and decided to go for a baker’s dozen. With one out, Seguignol was safe on a fielder’s choice, moved to second on Wilton Guerrero’s single, and scored on a Coquillette base hit. That was Coquillette’s third hit of the game, the only time he accomplished the feat in his 51-game major-league career. Final score: Montreal 13, Philadelphia 3.

Guerrero hit one more home run in his last game of the year to bring his total to 42, along with 131 RBIs and a .316 batting average. He set a career high in home runs with 44 in 2000, the only other time he hit more than 40 in a season.

This article appeared in “Au jeu/Play Ball: The 50 Greatest Games in the History of the Montreal Expos” (SABR, 2016), edited by Norm King. To read more articles from this book, click here.

Sources

In addition to the sources listed in the notes, the author consulted:

Baseball-reference.com.

Standard Speaker (Hazleton, Pennsylvania).

Ucs.mun.ca.

Box scores for this game can be seen on baseball-reference.com, and retrosheet.org at:

http://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/PHI/PHI199910020.shtml

http://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1999/B10020PHI1999.htm

Notes

1 Stephanie Myles, “Oh, what a night!,” The Gazette (Montreal), October 3, 1999.

2 Literally translated, “nos amours” means “our loves.” The term was an affectionate nickname for the team.

3 Myles.

4 Ibid.

Additional Stats

Montreal Expos 13

Philadelphia Phillies 3

Veterans Stadium

Philadelphia, PA

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.