October 3, 1951: The Giants Win The Pennant!

On August 11, 1951, the second-place New York Giants trailed their rivals, the Brooklyn Dodgers, by 13 games. From that point until the end of the season, the Giants won 39 of their final 47 games, an incredible .830 clip. The 154-game season ended with both clubs tied for the top spot in the National League, necessitating a three-game playoff series. After splitting the first two contests, the foes faced off at the Polo Grounds on October 3 for the deciding game.

Despite the high stakes, it was a relatively-disappointing crowd that made its way to the ballpark that afternoon. Perhaps it was the threat of rain in the forecast, or maybe the 10-0 drubbing that the Dodgers had inflicted on the Giants the previous day. Whatever the excuse, only 34,320 fans were in attendance. In the ensuing decades, tens of thousands more would claim that they were there. What the no-shows missed was one of the most legendary games in baseball history.

The Giants were managed by Leo Durocher, who chose Sal “The Barber” Maglie as his starting pitcher. Maglie had gotten his nickname either because he usually looked like he hadn’t shaved, or because the fearless pitcher liked to welcome batters to the plate with a little chin music. He had won 23 games so far that season, including five against Brooklyn. His mound opponent for Charlie Dressen’s Dodgers was hard-throwing Don Newcombe, who had won 20.

The Dodgers drew first blood, when Pee Wee Reese scored on a one-out single by Jackie Robinson in the opening frame. Maglie pitched his way out of further damage, however.

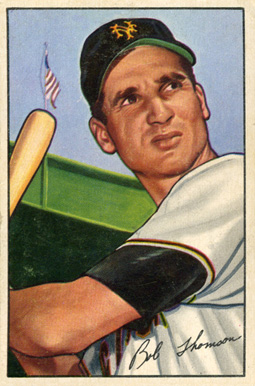

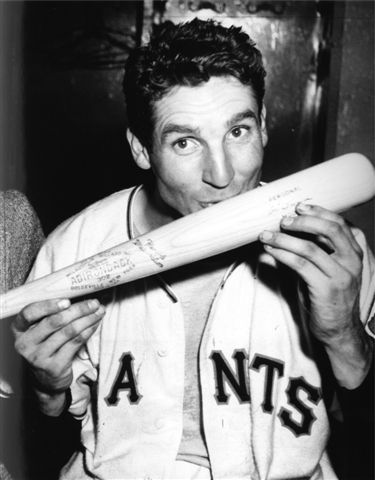

In the bottom of the second, the Giants Whitey Lockman singled with one out, bringing up Bobby Thomson, New York’s 27-year-old third baseman, who had been sizzling down the stretch. Earlier, on his way to the ballpark, Thomson had said to himself that it would be great if he could somehow get three hits that day. He got off to a good start in this at-bat, lining one down the left field line. Thinking double all the way, he rounded first with his head down, racing for second. The Dodgers left fielder, Andy Pafko, had a rifle for an arm, and Lockman, not wanting to get thrown out at third, held at second. Pafko threw the ball to shortstop Reese. Thomson was suddenly caught in no-man’s land between first and second, and he was out on Reese’s relay to first baseman Gil Hodges. It was a costly base-running gaffe by Thomson. Instead of runners on first and second with one out, the Giants now had a runner on second with two down. The next batter, Willie Mays, flied out to end the inning. For the moment, Thomson wore the goat horns. In the darkening gloom, the Polo Grounds lights were turned on.

In the fifth, Thomson, still wielding a hot bat, doubled to left. His mates, however, were unable to drive him in, and the score stood 1-0 in favor of the Dodgers. It remained that way until the seventh, when Thomson’s deep fly to center scored Monte Irvin from third.

In the eighth, the wheels fell off for the Giants and the exhausted Maglie, as the Dodgers scored three runs to take a commanding 4-1 lead before the Barber was replaced by Larry Jansen. Newcombe, meanwhile, was seemingly growing stronger.

Then came the bottom of the ninth. Many of the Polo Grounds crowd had already begun making their way to the exit ramps. Alvin Dark singled to open the inning. The next batter, Don Mueller, noticed that Dodger first baseman Gil Hodges was playing close to the bag, as Dark edged his way off first. It was an odd strategy on Hodges’s part; there wasn’t much chance of Dark attempting to steal. The Giants, after all, needed base runners. Mueller hit a slow grounder to Hodges’s right, just out of his reach. Had the first baseman been playing wider of the bag, he may have easily gobbled it up and started a double play. It went as a single to right field, however, with Dark taking third.

Monte Irvin, the leading RBI man on the Giants and their best clutch hitter, fouled out to Hodges for the first out. At that point, an announcement was made in the press box that World Series credentials for Brooklyn’s Ebbets Field could be picked up later that evening at the Biltmore Hotel.

Lockman, the next hitter, doubled to left, scoring Dark and sending Mueller to third. Mueller slid awkwardly into the bag, injuring his ankle. Thus, in the middle of the mounting excitement, the game was halted for several moments as Mueller was carted off the field, pinch-runner Clint Hartung taking his place. “The corniest possible sort of Hollywood schmaltz,” wrote Red Smith, “stretcher bearers plodding away with an injured Mueller between them, symbolic of the Giants themselves.”1

Next up, Bobby Thomson. To face him, Dressen brought in Ralph Branca. The Brooklyn righty had been the starter in Game One, giving up a homer to Thomson but pitching well in a 3-1 loss.

Gordon McClendon was calling the game on radio for the Liberty Broadcasting System. “Boy, I’m telling you!” he declared. “What they’re going to say about this one I don’t know!”2 Branca somehow sneaked a fastball down the middle for strike one. “A ball I should have swung at,” Thomson, a fastball hitter, admitted later.3

At 3:58 pm, Branca’s second pitch, another fastball, came in high and tight. Thomson swung, his uppercut driving the ball deep toward the corner in left. Pafko, dashing toward the high wall, ran out of room. The ball landed in the first row, just above the 315 ft. sign for a three-run home run. Game over. The Polo Grounds shook as the euphoric crowd erupted. Joe King wrote in The Sporting News, “(Thomson’s homer) touched off scenes in this place which never before had been witnessed in connection with the winning of a pennant.”4

At 3:58 pm, Branca’s second pitch, another fastball, came in high and tight. Thomson swung, his uppercut driving the ball deep toward the corner in left. Pafko, dashing toward the high wall, ran out of room. The ball landed in the first row, just above the 315 ft. sign for a three-run home run. Game over. The Polo Grounds shook as the euphoric crowd erupted. Joe King wrote in The Sporting News, “(Thomson’s homer) touched off scenes in this place which never before had been witnessed in connection with the winning of a pennant.”4

By any measure, and for pure excitement, Thomson’s home run, referred to down the years as “The Shot Heard ‘Round the World,” belongs on the short list of the most legendary in baseball history. Some consider it the most famous blast ever. Much of the mystique surrounding the home run lies in the iconic, delirious radio call by Giants broadcaster Russ Hodges (“The Giants win the pennant! The Giants win the pennant! The Giants win the pennant! The Giants win the pennant!”)5Dodger broadcaster Red Barber’s call summed it up: “It is…a home run! And the New York Giants win the National League pennant and the Polo Grounds goes wild!”6 Gordon McClendon described the home run this way: “Going, going gone! The Giants win the pennant!” Then, after a brief pause, “I don’t know what to say! I just don’t know what to say! It’s the greatest victory in all of baseball history!”7 Ernie Harwell, calling the game on the Giants television network, simply said “It’s gone!”8Felo Ramirez, describing the game in Spanish for Latin-American listeners, cried “Los Gigantes son los campeones!”9

As Thomson raced around the bases to be greeted at home by a throng of ecstatic teammates, the stunned Dodgers began the long walk off the field. All except Jackie Robinson, who can be seen in a well-known photograph taken from center field looking in toward second base. The photo shows the scrum of players at home plate, with Thomson somewhere in the middle. Branca, head hanging, is walking dejectedly away from the mound. Robinson, standing all alone just beyond second base, his back to the camera, is staring, hands on hips, toward home, in order to make sure that Thomson actually touched the plate. It is one of the classic photos of sport, a poignant juxtaposition of dejection and giddy victory. Bobby Thomson had certainly gotten his three hits.

Probably no one in the old ballpark was more delighted at Thomson’s home run than the on-deck hitter, rookie Willie Mays, who later admitted he was terrified at the prospect of having to bat in such a pressure-packed situation.

Branca, of course, took the loss, while Jansen, who pitched one inning, got the win, his 23rd of the season.

Attending the game that day was the motley quartet of comic actor Jackie Gleason, New York restaurateur Toots Shor, FBI chief J. Edgar Hoover, and crooner Frank Sinatra (who had been given four tickets by Durocher). The group had been drinking all day, and just before Thomson hit his home run, Gleason unceremoniously threw up in the lap of Sinatra, a Giant fan. Said Sinatra later, “The fans are going wild and Thomson comes to bat. Then Gleason throws up all over me! Here’s one of the all-time games and I don’t even get to see Bobby hit that homer! Only Gleason, a Brooklyn fan, would get sick at a time like that!”10

Not only did the game feature perhaps the most famous home run ever hit, the most famous radio call in sports broadcasting history, and one of the most iconic sports photos, but it resulted in one of the most wonderful leads ever in a newspaper article. The day after the game, Red Smith, writing in the New York Herald-Tribune, opened his story “Miracle of Coogan’s Bluff” with the famous lines: “Now it is done. Now the story ends. And there is no way to tell it. The art of fiction is dead. Reality has strangled invention. Only the utterly impossible, the inexpressibly fantastic, can ever be plausible again.”11

This article appeared in “The Team That Time Won’t Forget: The 1951 New York Giants” (SABR, 2015), edited by Bill Nowlin and C. Paul Rogers III.

Notes

1 Red Smith, “Miracle of Coogan’s Bluff,” New York Herald-Tribune, October 4, 1951.

3 Ray Robinson, The Home Run Heard ‘Round the World (Mineola, New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 2011).

4 Joe King, “Giants Playoff Win Sets New High in Drama,” The Sporting News, October 10, 1951.

5 Joshua Prager, The Echoing Green (New York: Pantheon, 2006), 220, 221.

6 Prager, 220, 221.

7 Prager, 220, 221.

8 CBSSports.com wire report, “Longtime Tigers Broadcaster Harwell dies at 92,” http://www.cbssports.com/mlb/story/13346545/longtime-tigers-broadcaster-harwell-dies-at-92, accessed February 15, 2014

9 Prager, 220, 221.

10 Robinson, 241.

11 Smith.

Additional Stats

New York Giants 5

Brooklyn Dodgers 4

Game 3, NL tiebreaker

Polo Grounds

New York, NY

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.