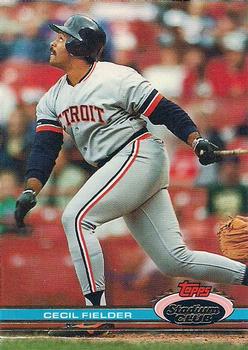

September 14, 1991: When Cecil Fielder’s home run left the ballpark

It seemed an optimistic but relatively inconsequential signing at the time. In January 1990, the Detroit Tigers, coming off an abysmal 59-103 last-place season and in search of a power upgrade, gave a little-known and heretofore mostly unproductive former major leaguer named Cecil Fielder a $1.25 million incentive-laden contract and installed him as their starting first baseman. Just over a year before, Fielder must have questioned whether his brief career was over. In four frustrating years with the Toronto Blue Jays, the man they called Big Daddy because of his massive frame (6-feet-3 and anywhere from 230 to 280 pounds), had shown flashes of immense power but also a proclivity to strike out. Given his failure to break into Toronto’s starting lineup, in December 1988 the Blue Jays gave up on Fielder and sold his contract to the Hanshin Tigers, in the Japanese Central League.

It seemed an optimistic but relatively inconsequential signing at the time. In January 1990, the Detroit Tigers, coming off an abysmal 59-103 last-place season and in search of a power upgrade, gave a little-known and heretofore mostly unproductive former major leaguer named Cecil Fielder a $1.25 million incentive-laden contract and installed him as their starting first baseman. Just over a year before, Fielder must have questioned whether his brief career was over. In four frustrating years with the Toronto Blue Jays, the man they called Big Daddy because of his massive frame (6-feet-3 and anywhere from 230 to 280 pounds), had shown flashes of immense power but also a proclivity to strike out. Given his failure to break into Toronto’s starting lineup, in December 1988 the Blue Jays gave up on Fielder and sold his contract to the Hanshin Tigers, in the Japanese Central League.

There Fielder turned his career around. Having hit 31 home runs in 506 at-bats with Toronto, in Japan Fielder produced 38 in only 384 at-bats. Most of those blasts, too, were prodigious, so the Tigers took a chance and signed Fielder. Little could they have anticipated how great and immediate would be the return on their investment.

Asked on the first day of spring training for his impressions of his new first baseman, Tigers manager Sparky Anderson replied, “I know he can hit the ball a long way.”1Just how far became evident in the Tigers’ sixth game of the season, on April 14. Playing at home against the Baltimore Orioles and their starter, Dave Johnson, the right-handed-hitting Fielder crushed his first home run of the season deep into the upper deck in right field. Four days later he blasted his second, this time into the upper deck in left field. “That’s where the big boys hit ’em,” observed Anderson after the game.2

As the season progressed, Fielder’s home-run total climbed, spurred by several multi-homer performances. On April 28, at home against the Milwaukee Brewers, he hit two; in Toronto on May 6, he hit three, a total he repeated exactly one month later in Cleveland. By the All-Star break, Fielder’s total stood at 28.

On August 25, 1990, Fielder hit his most monstrous homer to date. That night, the Oakland A’s were in town for the second game of a three-game series. Gritty veteran starter Dave Stewart, on the mound for Oakland, was staked to a 3-0 first-inning lead. With two outs and a man on third in the bottom of that inning, Fielder swung at a Stewart pitch and “crushed it onto and over the roof in left field. For a moment everyone in the ballpark just stopped what they were doing and stared. … Fielder tossed his bat and watched the ball disappear like everyone else.”3

“That one’s loooooong gone!!!” legendary Tigers announcer Ernie Harwell told his radio listeners.4

Fielder hit one more home run that night. By the end of August he had 42. Going into the final game of the season, on October 3 at Yankee Stadium, he had hit 49. That night, he blasted two more homers, and finished his magical season with 51. Whatever were the incentives in Fielder’s contract, he assuredly earned them in 1990.

In 1991 Fielder picked up where he’d left off. In July he delivered three two-homer games, and as August began his total stood at 29. On September 11 Fielder hit his 40th, against the Boston Red Sox at Tiger Stadium. After that game, the Tigers traveled to Milwaukee to take on the Brewers in a four-game series. Fielder was soon to make history.

It had been a relatively quiet year for the Brewers. After a poor start to the season, a good August showing had pushed their record near .500; their 7-0 win in the series’ first game, on September 12, left them with a 4-5 record in September, 66-72 for the year, and firmly entrenched in fourth place in the AL East. After the Brewers lost game two, Milwaukee manager Tom Trebelhorn sent left-hander Dan Plesac, normally a reliever but recently added to the starting rotation, to the mound for the third game, played on Saturday night, September 14. As was customary, Fielder batted fourth for the Tigers. A crowd of 26,644 was on hand in County Stadium; for years afterward, though, that attendance likely seemed to be 50,000, as many who weren’t there undoubtedly told a vicarious tale of what they would have liked to witness that night.

Over the first three innings, not much happened offensively for either team, although each left two men on in an inning, the Brewers in the first and the Tigers in the third. So as the fourth inning arrived, the game was a scoreless tie. In the top of the fourth, Fielder led off for Detroit — and he wasted no time giving the Tigers the lead. On Plesac’s first pitch, Fielder swung and drove the ball deep to left. The wall in left field displayed the distance of 362 feet. Fielder’s blast cleared the 10-foot-high wall just to the left of that sign and kept on climbing. On the wall behind and atop the left-field bleachers stood another fence, and Fielder’s shot cleared that fence too, leaving the stadium completely and coming to rest near a garbage bin beyond the exterior stadium wall. In baseball parlance, Fielder had “gotten it all,” and in doing so became the first player in the 22-year history of Milwaukee County Stadium to clear the permanent left-field bleachers with a home run. Afterward, the shot was estimated to have traveled 520 feet. No one else would do it again.

In the end, the Tigers won the game, 6-4. With one out in the fifth, Detroit slugged, consecutively, a double, triple, and sacrifice fly to score two runs and boost their lead to 3-0; then in the sixth, Greg Vaughn blasted a solo home run for the Brewers, making the score 3-1. In the ninth, each team plated three runs, but Milwaukee could come no closer than the eventual two-run margin of victory. With a runner on second in the bottom of the ninth, the Brewers’ Robin Yount grounded out shortstop to first to end it.

Afterward, unsurprisingly, all anyone wanted to talk about was Fielder’s home run, and to draw comparisons with previous monumental blasts hit at County Stadium. Brewers president Bud Selig and Bob Buege, an author who had written a book on the Brewers’ predecessor in Milwaukee, the Braves, remembered the Braves’ Joe Adcock hitting one over the same stands in the mid-1950s.5“I think it was the 1956 season,” recalled Buege. “As I recall it was estimated at 475 feet because it was compared to one hit into the center-field bleachers in the Polo Grounds, the first one that was hit there.”6

Likewise, Brewers radio broadcaster Bob Uecker, a former Braves player, recalled two long homers during his time in Milwaukee. “Willie McCovey hit one off the base of the scoreboard off Pat Jarvis,”7Uecker said, “and Adcock hit one into the trees in center field. I haven’t seen one longer than the one Cecil hit, but the one hit by McCovey went a long, long way.”8

The day after Fielder’s home run, a Brewers scoreboard crew member brought to the park a copy of The Sporting Newsdated June 17, 1959. It had a story that said the San Francisco Giants’ Orlando Cepeda had hit a home run on June 4 of that season that was the first to clear the left-field stands at County Stadium. It was estimated to have traveled 500 feet.

Finally, Tigers broadcaster Harwell, who had witnessed Fielder’s exploits up-close, expounded on both the home run that left Tiger Stadium and the County Stadium blast. “That one [the Tiger Stadium homer] may have been farther,” Harwell said, “but once again it’s so hard [to judge] because the configurations are different. This one was a lot better because you could see it disappear. That one over the roof, you could just see it go on the roof. On that roof, there’s sort of an apex and it went over there. They say a gutter caught it at the bottom of the other side.”9

It was left for Fielder himself to give the best explanation of his home run. “I hit the ball good, made good contact and it traveled a long way. That’s about it.”10

Indeed it was.

This article appears in “From the Braves to the Brewers: Great Games and Exciting History at Milwaukee’s County Stadium” (SABR, 2016), edited by Gregory H. Wolf. To read more stories from this book at the SABR Games Project, click here.

Sources

Milwaukee Journal.

Lowry, Philip J. Green Cathedrals: The Ultimate Celebration of Major League and Negro League Ballparks(New York: Walker Publishing Co., 2006).

baseball-reference.com.

retrosheet.org.

Notes

1blog.detroitathletic.com/2015/01/22/big-daddy-came-detroit/.

2Ibid.

3Ibid.

4Ibid.

5At the time, the left-field stands were not permanent; they were movable, to accommodate football, so it’s not believed that any ball before Fielder’s actually left the ballpark.

6Milwaukee Journal, September 16, 1991.

7It’s unclear when the McCovey home run may have occurred, or even if it was surrendered by Pat Jarvis, as Jarvis pitched for the AtlantaBraves from 1966 to 1972.

8Milwaukee Journal, September 16, 1991.

9Ibid.

10Ibid.

Additional Stats

Detroit Tigers 6

Milwaukee Brewers 4

County Stadium

Milwaukee, WI

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.