September 2, 1880: Night baseball at Nantasket Beach

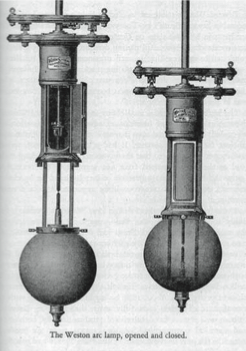

Weston arc lamp, circa 1880s (Library of Congress)

Today many major league baseball games are played under artificial illumination. In the first few decades of “base ball” playing, however, games were often curtailed due to darkness. The increasing number of electric lighting systems being installed in the late 1870s made experimentation with artificial illumination at ball games almost inevitable.

The first known such experiment occurred during the evening of Sept. 2, 1880, when two teams, mostly employees from the dry-goods firms R. H. White and Company and Jordan Marsh and Company, played a nine-inning game on the back lawn of the Sea Foam House, a hotel near Nantasket Beach in Hull, Mass.

At that time, the prevailing means of nighttime artificial illumination was gas. But various electrical lighting firms were created to challenge the monopoly of the gas companies. The Boston-based Northern Electric Light Company, perhaps desiring a venue where thousands of people might be able to view a sample of the potential of their lighting equipment, erected at the beach three wooden towers 500 feet apart in an equilateral triangle. Each was 100 feet high, and mounted upon each of these was a circular row of 12 electrical lights “of the Weston patent.” Each light had an estimated 2,500 candle power; thus, the light of 90,000 candles was concentrated within a limited territory. The company used three “Weston machines,” undoubtedly dynamos, to generate “a motive-power of 36 horses,” that is 36 horsepower.1

The mention of “Weston” equipment is an indication that the lighting apparatus involved was not incandescent lamps (invented by Thomas Edison a year earlier in 1879 and in which a filament gives off light when heated to incandescence by an electric current), but rather the electric arc lamps (electrical lamps that produce light by an arc made when a current passes between two incandescent electrodes surrounded by gas) and electric dynamos developed by Edward Weston. In 1873 he established the Harris & Weston Electroplating Company in partnership with George G. Harris, and in the same year he developed his first dynamo (a machine used to convert mechanical energy into electrical energy) for electroplating. Two years later, Weston patented what he called the “rational construction of the dynamo,” which enabled him, so he claimed, to increase its efficiency from 45 percent to more than 90 percent.

The New England Weston Electric Light Company was possibly a collaborator, perhaps with the idea that playing a base ball game under artificial illumination might bring added attention to its equipment. But it certainly had in mind a market much more extensive than just ball fields. The Boston Herald noted, “The design of the exhibition was to afford a model of the plan contemplated for lighting cities from overhead in vast areas, the estimate being that four towers to a square mile of area, each mounting lights aggregating 90,000 candle power, will suffice to flood the territory about with a light almost equal to mid-day.”

Reporters at the game assessed that the amount of lighting was insufficient for good ball play. Although reporting that the lights, with one single slight flicker, “burned steadily and brilliantly all evening” between 8 and 9:30 p.m., the Herald observed that “on account of the uncertain light, (resembling that of the moon at its full,) the batting was weak and the pitchers were poorly supported.” The historian Preston Orem summarized accounts in several Boston newspapers to conclude, “The light was quite imperfect and there were lots of errors made. The players had to bat and throw with caution. For the spectators the game had little interest as only the movements of the pitcher, in general, could be discerned, while the course of the ball eluded the vision of the watchers. … None of the reporters believed the idea to be at all practical.”2

The game ended in a 16–16 tie after nine innings, with further play precluded by the desire of the players to catch the last ferry boat back to Boston. What the electric companies involved officially concluded from the experiment is not known. But The Boston Evening Transcript concluded that “if the projectors of the experiment wish to convince the public that they can shed light enough over a city from elevated stands to allow people to sit in their houses and pursue their ordinary evening occupations without gas, candle or lamp light, more light still will be necessary.”3

Arc-lamp outdoor lighting from a system of high towers, known as moonlight towers, did become briefly popular in the 1880s and 1890s in several cities in the United States and Europe. But the numbers of such towers decreased as incandescent electric street lighting became more common.4

The contemporary accounts of the Nantasket Beach night game make no mention of individual participating players, which may have been deliberate. In 1909, nearly 30 years after it was played, an anonymous correspondent, stating that he had been the “Official Scorer” of the game, wrote to the New York Sun newspaper and claimed that “at almost the last moment the two firms mentioned [for an unspecified reason] forbade their employees taking part, so it was played sub rosa.” The ban by the companies, according to the correspondent, made it “inexpedient [for him] to mention any names of players, as some of them may still be employed in these establishments, although a number of players were recruited from the various jobbing houses in the dry-goods trade.”

Northern Electric did reward the players and officials for their efforts with a fine post-game supper (probably in Boston), of which the Sun correspondent had “the most vivid remembrance.”5

Notes

1 “Electric Lights in a Cluster,” New York Times, vol. 29, no. 9045, September 4, 1880, p. 3, col. 7, reprinted from the Boston Herald, September 3, 1880. The Herald’s account was also reprinted in The Annual Register: A Review of Public Events at Home and Abroad, for the Year 1880, new series, vol. 122 (London: Rivingtons, 1881), p. 88.

2 Orem, Preston. Baseball 1845-1881 From the Newspaper Accounts (Altadena, Calif.: Self-published, 1961), p. 342.

3 The passage is quoted in the Appendix item “September 2, 1880: The Latest Yankee Notion” p. 176-177 in Troy Soos, Before the Curse: The Glory Days of New England Baseball, 1858-1918, rev. ed. ( Jeffereson, N.C., and London: McFarland & Company, 2006).

4 For a lengthy, illustrated account of these structures, see the Wikipedia article “Moonlight tower.”

5 The passage from the letter to the Sun by “Official Scorer” was reprinted in William Shepard Walsh, A Handy Book of Curious Information (Philadelphia and London: J. B. Lippincott Company, 1913), p. 107.

Additional Stats

R.H. White & Co. 16

Jordan Marsh & Co. 16

Sea Foam House, Nantasket Beach

Hull, MA

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.