September 22, 1935: Satchel Paige takes the money but not the mound at Yankee Stadium

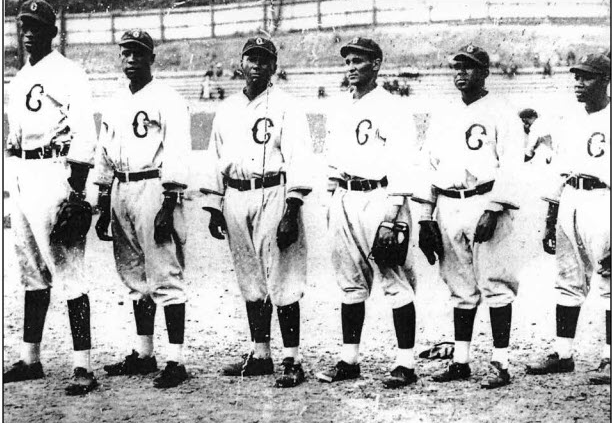

1934 Pittsburgh Crawfords pitchers, from left: Satchel Paige, Leroy Matlock, William Bell, Harry Kincannon, Sam Streeter, and Bertrum Hunter. All were expected to return in 1935, but Paige held out and Bell joined the Brooklyn Eagles in midseason. (CENTER FOR NEGRO LEAGUE BASEBALL RESEARCH)

Although the 1935 Pittsburgh Crawfords had performed remarkably well during the regular season and postseason even without ace Satchel Paige, who had gone 13-3 with a 1.54 ERA for Pittsburgh in 1934, the tall, slender hurler was already a legend who still ranked among the best players in the Negro Leagues. However, Philadelphia’s Slim Jones had bested Paige the previous season, as the young southpaw went 20-4 with a 1.24 ERA for the 1934 Stars. The two hooked up after the season in a game that, a historian said, “would become known as ‘The Greatest Negro League Game Ever,’” adding, “Over 30,000 fans watched Slim sling a six-inning perfect game to lead Satch’s squad 1-0. Oscar Charleston broke it up in the seventh and … Pittsburgh … pushed across a run to tie. Slim and Satch dueled mightily, trading strikeouts until the heart-pounding nail biter was called by nightfall in the tenth.”1

Paige got married less than seven weeks after the game, and Pittsburgh owner Gus Greenlee gave his hurler an unusual wedding present: “With his guests expecting a wedding toast, the Crawfords’ owner threw a curve. ‘Satchel won’t be leaving us, don’t worry about that.’ Gus announced, arm around his star. ‘I got a new contract here for him.’ Satchel and Gus sat down and signed right there, as they had agreed beforehand.”2

Paige did not fulfill the first year of his contract, opting instead to play semipro ball in North Dakota. Greenlee “was so miffed that he had Paige barred from the league for 1935. … Chester Williams wrote a tentative, premature obituary in the Pittsburgh Courier: ‘The champ of today may be the chump of tomorrow. So it may be with Paige. The league helped to make him and now the league may be the medium to break him.’”3

Hard feelings notwithstanding, the Crawfords took the title without Paige, and Greenlee sought to re-create the magical matchup of 1934 by having his squad take on Philadelphia again on September 22, 1935. A New York Amsterdam News article touted the highly anticipated matchup by declaring, “Satchel Paige vs. Slim Jones! This is the attractive centerpiece of the big four-team Negro National League double-header slated Sunday at the Yankee Stadium as the Pittsburgh Crawfords and Philadelphia Stars, arch foes in colored baseball, come to grips in the featured game.”4 The first game, an afterthought in light of the premier second-game matchup, pitted the Nashville Elite Giants against the New York Cubans.5 Greenlee paid Paige the handsome sum of $350 to pitch, but Satchel did not show for the game that took place just two days after the Crawfords had topped the New York Cubans in the seventh game of the 1935 Negro National League Championship Series.

Paige’s failure to appear was not entirely unusual for a player whom the Amsterdam News termed “as eccentric and talented as the late Rube Waddell,”6 but Satchel’s absence obviously made the sequel far less satisfying than the original. The fact was that “a crowd of more than 15,000 fans were disappointed at Yankee Stadium Sunday … when Satchel Paige, star pitcher, failed to appear as advertised and when ‘Slim’ Jones, who last year beat Paige in a pitching duel, was knocked out after only one inning on the mound.”7 Greenlee informed the press that Paige had stopped in Chicago en route to the Empire State for the big doubleheader and had been offered $500 to pitch for the Kansas City Monarchs on September 22. Typical for Paige, the higher dollar amount “caused him to forget all about his agreement to appear in New York.”8

Pittsburgh had survived without Paige all season and did so again in the exhibition game against the Stars. In fact, “The Crawfords, with their new world crown posing jauntily askew on their kingly brows, put on an exhibition of sheer pulverizing power that left the crowd and the Philadelphia Stars as well completely stunned and thoroughly convinced that they were the boys who REALLY deserve to reside in the thrown [sic] room of Negro baseball.”9

Earnest “Spoon” Carter took the mound for the Crawfords and went the distance as Pittsburgh pounded its intrastate rivals, 12-2. With a 4-5 record and a 5.88 ERA, Jones had slipped severely from his star turn in 1934 and surrendered four runs in his lone inning of work. Relievers Webster McDonald, the ace of the 1935 Stars with an 8-4 record and a 4.30 ERA, and Rocky Ellis fared no better than Jones. Any notion that the game would be as competitive as the previous year’s contest vanished quickly. “From the moment that ‘Cool Papa’ Bell opened the game with a blistering double to deep left field, the Pittsburgh power attack kept up a steady bombardment,” and the Crawfords scored in each of the first five innings to build a 12-1 lead.10

The Crawfords outhit the Stars, 20 to 10, and belted four home runs. Pat Patterson and Bill Perkins smacked one home run apiece while “[s]hortstopper Chester] Williams hit two of the round-trippers. Every one of the Crawfords managed to get himself at least one safe hit. Young Addie Ward, Quaker City centerfielder, scored both of the Stars’ runs.”11

Pittsburgh had again shown that it could win easily without Paige, but bad publicity resulted from the star hurler’s no-show. On October 5 the Amsterdam News reported that “a number of fans [are] all het up over the non-appearance of Satchel Paige” for the Jones rematch. “[M]any fans remarked that they would not have been present had they known that Paige would not be on hand.”12

Daily Mirror columnist Dan Parker asserted, “Promoters of the colored baseball games at Yankee Stadium last week advertised Satchel Paige as one of the players, though they knew he was playing in Chicago that day. This cheap gag is used on other large cities, too. It surprises me that Satchel doesn’t sue for damages.”13 Given that Greenlee had wired money to Paige as payment for his September 22 appearance, the Amsterdam News countered, “From what could be gleaned on this end of the unfortunate affair it would seem that Satchel is the one who is surprised that he isn’t being sued.”14

Whether the greater sum of $500 offered by the Monarchs was the sole reason why Paige got paid but did not play remains lost to history. Perhaps his resentment had built up and resulted in his seeking payback for Greenlee’s season-long ban. Or perhaps Paige just did not feel like coming to New York on this particular day. Negro League players, even stars, rarely got the last word, but Paige later explained his general outlook in his autobiography, stating, “Before I went with the Monarchs, I hadn’t thought anything about jumping contracts when I felt like it. I guess I never cared much about anything except myself. It’d made guys like Abe Saperstein … and Gus Greenlee and Candy Jim Taylor and lots others mad at me because of that.”15

This article was published in “Pride of Smoketown: The 1935 Pittsburgh Crawfords” (SABR, 2020), edited by Frederick C. Bush and Bill Nowlin.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Rick Bush for his helpful edits and additions.

Notes

1 Jack Morelli, Heroes of the Negro Leagues (New York: Abrams Books, 2007), 120. Paige struck out 12 in the tie. Jeremy Beer, Oscar Charleston (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2019), 243.

2 Larry Tye, Satchel (New York: Random House, 2009), 75.

3 Robert Peterson, Only the Ball Was White (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1984), 134.

4 “Yankee Stadium Diamond Games Season’s Most Attractive: Mound Aces Set for Big Battles,” New York Amsterdam News, September 21, 1935: 13.

5 The opening game of the doubleheader ended up as the better game of the day with Nashville surviving a ninth-inning rally by the Cubans to hold on to a 4-3 victory.

6 “Yankee Stadium Diamond Games Season’s Most Attractive: Mound Aces Set for Big Battles.”

7 William E. Clark, “15,000 Fans See 4-Team Series at Yankee Stadium Sunday; Crawford and Elite Gts, Win,” New York Age, September 28, 1935.

8 Clark.

9 Joe Bostic, “Thousands See Defeats of Cubans and Stars,” New York Amsterdam News, September 28, 1935: 12.

10 Bostic.

11 Bostic. This game may have represented Ward’s best effort with the Stars. Given that he would turn 26 less than two months after this game, Ward does not retrospectively appear particularly young in baseball terms. The Seamheads database lists Ward’s first name as Willie; Addie comes from his middle name (Addison). According to the database, Ward played in only one regular-season game for Philadelphia during which he scored a single run. See seamheads.com/NegroLgs/player.php?playerID=ward-01wil (accessed October 18, 2019).

12 Artie La Mar, “Fans All Het Up Over Non-Appearance of Paige at the Yankee Stadium Games Here,” New York Amsterdam News, October 5, 1935: 13.

13 La Mar.

14 La Mar.

15 LeRoy (Satchel) Paige as told to David Lipman, Maybe I’ll Pitch Forever (Lincoln: Bison Books, 1993), 141.

Additional Stats

Pittsburgh Crawfords 12

Philadelphia Stars 2

Yankee Stadium

New York, NY

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.