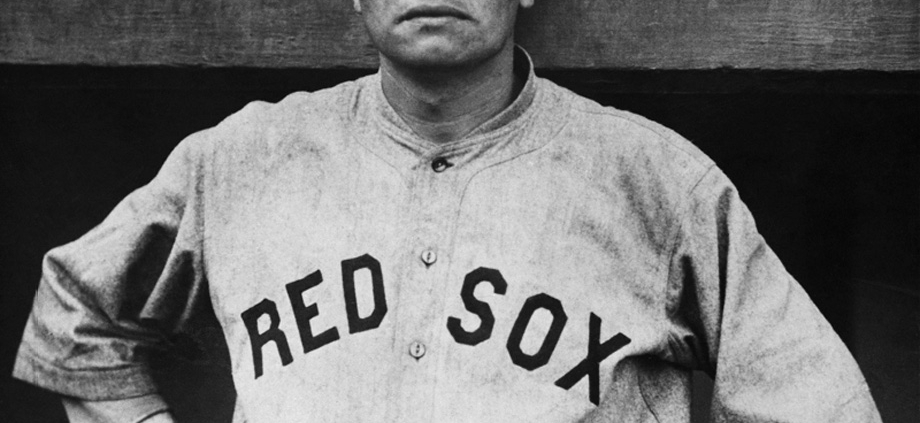

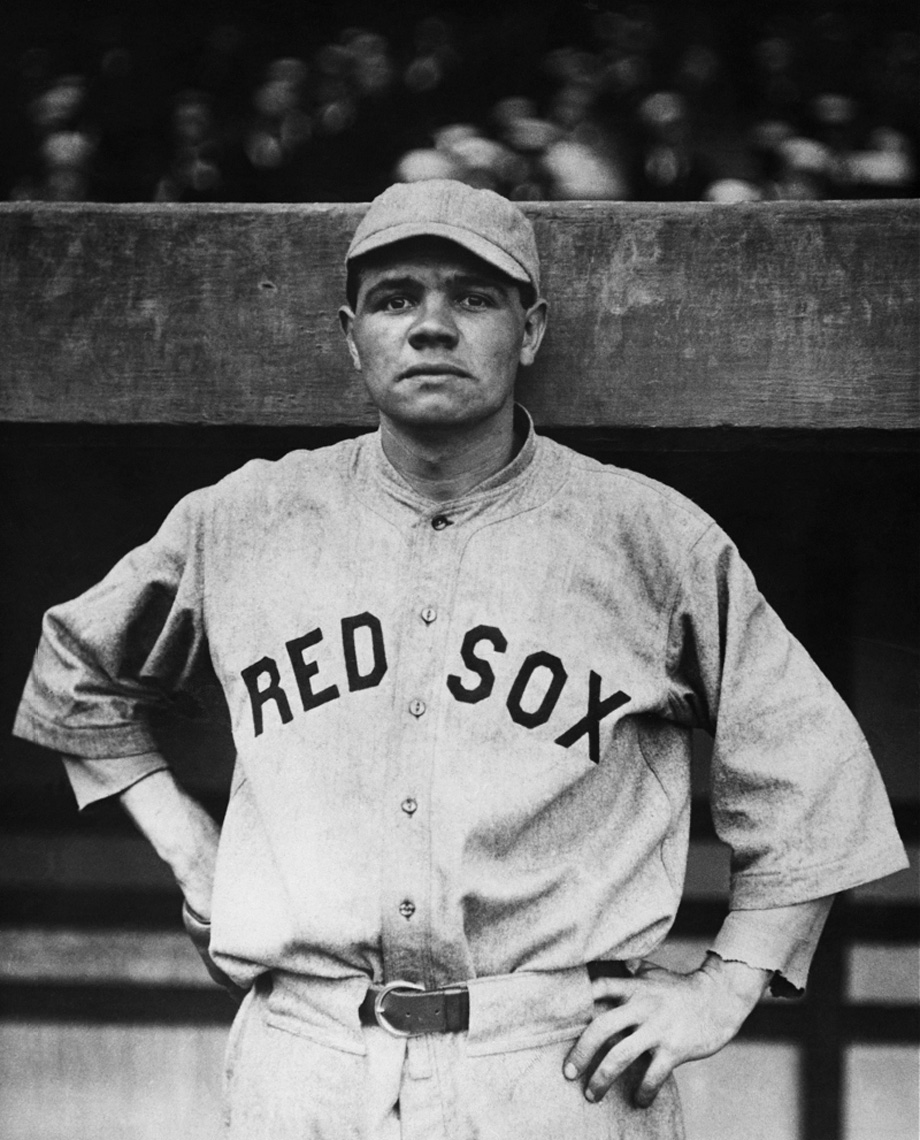

September 24, 1919: Babe Ruth passes Ed Williamson’s mark with record 28th home run of season

Babe Ruth wanted more money. The star pitcher and home-run hitter for the Boston Red Sox made $7,500 in 1918. He hoped to double that figure the following season. Ruth and Red Sox owner Harry Frazee, a theatrical producer, talked over a deal, the Babe deciding to hold out for top dollar. Both sides haggled even as spring training began in Florida. Finally, Ruth agreed to a three-year contract worth $10,000 per season. He had asked for more, but it was still a nice raise.

Babe Ruth wanted more money. The star pitcher and home-run hitter for the Boston Red Sox made $7,500 in 1918. He hoped to double that figure the following season. Ruth and Red Sox owner Harry Frazee, a theatrical producer, talked over a deal, the Babe deciding to hold out for top dollar. Both sides haggled even as spring training began in Florida. Finally, Ruth agreed to a three-year contract worth $10,000 per season. He had asked for more, but it was still a nice raise.

Ruth planned to give up his mound duties. “I’ll win more games playing every day in the outfield than I will pitching every fourth day,” he told reporters.1 The left-hander had established himself as one of the game’s top hurlers, compiling a career won-lost mark of 80-41 with a 2.09 ERA. He topped the American League with a 1.75 ERA in 1916. Red Sox manager Ed Barrow still wanted Ruth to pitch. The two had argued about this several times during 1918 when Ruth tied for the AL lead with 11 homers and went 13-7 on the mound. “If Ruth plays for the Red Sox in 1919,” Barrow said during Babe’s holdout, “he will probably pitch and pinch-hit.”2

Another thing: Ruth stayed out late. Very late. Sometimes the entire night. Barrow insisted that the young ballplayer get some sleep. Stop breaking curfew, Barrow barked at The Babe. The skipper even talked hotel porters into turning snitch. “When he comes in tonight, you come to my room and tell me,” Barrow said. “Wake me up.”3

One early morning, not long after Ruth rejoined the team, Barrow confronted his ballplayer. A fight nearly broke out. The two men argued and argued. After another incident, Barrow suspended The Babe. Finally, he pleaded with the 24-year-old wunderkind, a man not quite an orphan as a child, but close enough. “I know you had it tough as a kid,” Barrow said. “But don’t you think it’s time you straightened out and started leading a decent life now?”4 The Babe, contrite, agreed.

Barrow made Ruth happy during spring training. Babe roamed the outfield and batted cleanup. He hit pitches as far as some had ever seen. He smashed one ball “more than 500 feet,” according to a reporter.5 Or, said some, “more than 600 feet.”6 Barrow said the ball traveled 579 feet.7

On Opening Day, Ruth smacked a home run and then fell into a terrific slump. His batting average dropped to .180 after he went 0-for-3 on May 26. Then he got hot. Ruth batted .385 in June and hit four home runs. He ripped nine more in July and passed Ralph “Socks” Seybold to claim the American League record. Seybold hit 16 home runs for the 1902 Philadelphia Athletics.

Ruth added seven more homers in August. He also knocked “Cactus” Gavvy Cravath out of the record books. Cravath, one the early players to come out of Southern California, set the “modern era” mark (post-1900) after hitting 24 home runs while playing for the 1915 Philadelphia Phillies. Next up, the Washington Senators’ Buck Freeman, who established the pre-1900 record of 25 in 1899. Or so, most baseball experts believed. “This was considered the ultimate goal.”8 A diligent researcher discovered that Edward “Ned” Williamson once enjoyed an even bigger year than Freeman.

A compact (5-feet-11, 210 pounds), mustachioed infielder, Williamson knocked 27 home runs for the Chicago White Stockings of 1884. It didn’t hurt that Williamson played home games at Lake Front Park, one of baseball’s great bandboxes. The right-field fence stood just 215 feet from home plate, a cheap pop fly away. (Williamson, who died in 1894 from dropsy at the age of 36, set the single-season mark for doubles in 1883. Tip O’Neill of the St. Louis Browns broke that mark in 1887 when he recorded 52 two-base hits.)

Ruth, who “pitched in a regular turn in different stretches during the season,”9 in addition to playing left field and a little first base, tied Williamson’s mark on September 20 against the Chicago White Sox at Fenway Park. He broke the record four days later in the second game of a doubleheader against the New York Yankees. Boston won the first game, 4-0, at the Polo Grounds. Ruth went hitless in three at-bats, walked once and scored a run. The Yankees played “a listless game,” according to the New York Times.10 Sad Sam Jones hurled the shutout despite giving up five hits and walking nine batters. “Sam Jones was unable to control his sharp curve,” the Boston Globe reported, “and it broke before it reached the plate, with the result that (catcher) Wally Schang was hopping around like a headless chicken.”11 The fifth-place Red Sox upped their record to 66-67; the third-place Yankees dropped to 74-59.

Nineteen-year-old Waite Hoyt started for Boston in the second game against 28-year-old Bob Shawkey. New York went ahead 1-0 in the second inning on Wally Pipp’s single, a double by Del Pratt, and a run-scoring single by Duffy Lewis. Ruth lined out in his first at-bat and jogged to first after receiving an intentional walk in his second plate appearance. He “slammed” a Shawkey pitch in his third at-bat and should have gotten a triple. “But Ruth forgot to touch second base in his haste to get around and was declared out at the keystone sack.”12

Boston trailed 1-0 in the ninth inning when Ruth once again stepped to the plate. “He was the first man up, and his huge frame was shaking with anxiety to swing his bat on something tangible,” W.O. McGeehan wrote in the New York Tribune.13 The Times reported, “Ruth stood firmly on his sturdy legs like the Colossus of Rhodes.”14 Shawkey’s first pitch sailed “high and wide” and Ruth let it go by. Babe swung at the next offering, a big, slow curveball. He met the pitch and drove it deep and out of the ballpark. The Daily News, which called Ruth “the Boston Tarzan,” described the record-breaking home run as “a wonder,” adding, “It sailed far and high over the right-field stand. It was one of the longest hits ever seen at the Polo Grounds, if not the longest.”15 The New York Times agreed. “Ruth’s glorious smash yesterday was the longest drive ever made at the Polo Grounds.”16

The Boston Globe reported that “the 6,000 enthusiasts (at the Polo Grounds) who had watched the struggle arose and cheered the wonderful feat.” Ruth’s homer was, the Globe exclaimed, “unquestionably the most sensational batting achievement ever seen on the Polo Grounds.” After the ball “soared upward like the flight of a hawk,” it left the park and landed in Manhattan Field, “where it was retrieved by a little boy who disappeared with the trophy.”17

Ruth’s homer tied the game, 1-1. New York did not score in the bottom of the ninth. Hoyt and Shawkey continued battling in the extra innings. Ruth came to bat more time, in the 12th. He drove another Shawkey pitch into the air. “It looked as though it would climb into the 25-cent seats, but it fell inside and (Chick) Fewster (playing in center field) got it.”18 In the 13th, Pipp and Pratt combined again to produce a Yankee run. Pipp led off with a triple against Hoyt and sprinted home on Pratt’s fly ball to Ruth in left field. The game lasted 4½ hours.19

Losing pitcher Hoyt (4-6 for the season so far) threw a “remarkable game,”20 giving up five hits and none over one nine-inning stretch. On the other hand, “the Sox were hitting Shawkey (19-11) hard and often, and only the sharpest kind of fielding kept them from scoring at several stages of the play.”21

Writers devoted most of their attention to Ruth. The Daily News declared him an “absolute monarch of major-league four-base clouters.”22 The Boston Globe, mentioning the recent controversy surrounding Freeman and Williamson, noted that Ruth “established a world’s home-run record beyond all question, and one which may never be equaled.”23

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author used Baseball-Reference.com for player and team information.

Notes

1 Robert Creamer, Babe: The Legend Comes to Life (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1974), 187.

2 Ibid.

3 Creamer, 193.

4 Creamer, 195.

5 Creamer, 190.

6 Ibid.

7 Ibid.

8 Creamer, 201.

9 Leigh Montville, The Big Bam (New York: Doubleday, 2006), 89. Ruth went 9-5 with a 2.97 ERA in 1919. He threw 133⅓ innings. He pitched in only five more games in his career after 1919.

10 “Ruth Wallops Out His 28th Home Run,” New York Times, September 25, 1919: 10

11 “Ruth’s 28th Homer Ties Count in Second,” Boston Globe, September 25, 1919: 10.

12 Ibid.

13 W.O. McGeehan, “Babe Ruth Hits 28th Homer, Ball Clearing Roof of Stand,” New York Tribune, September 25, 1919: 16

14 “Ruth Wallops Out His 28th Home Run.”

15 “Yankees Battle Thirteen Rounds for Even Break,” Daily News (New York), September 25, 1919: 19.

16 “Ruth Wallops Out His 28th Home Run.”

17 “Ruth’s 28th Homer Ties Count in Second.”

18 Ibid.

19 Ibid.

20 Ibid.

21 Ibid.

22 “Yankees Battle Thirteen Rounds for Even Break.”

23 “Ruth Now Champion Home Run Swatter,” Boston Globe, September 25, 1919: 10.

Additional Stats

New York Yankees 2

Boston Red Sox 1

13 innings

Game 2, DH

Polo Grounds

New York, NY

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.