September 24, 1943: Cool Papa Bell wins Game 3 for Grays in 10th inning

Johnny Markham must have looked long and hard at Ted “Double Duty” Radcliffe. He knew what the signal meant and it must have been somewhat of a relief, even though it would load the bases. After all, who would want to pitch to Josh Gibson at all, let alone with freezing hands in Game Three of the Negro League World Series?

Johnny Markham must have looked long and hard at Ted “Double Duty” Radcliffe. He knew what the signal meant and it must have been somewhat of a relief, even though it would load the bases. After all, who would want to pitch to Josh Gibson at all, let alone with freezing hands in Game Three of the Negro League World Series?

Markham was a tough veteran from Shreveport, Louisiana, who had been in baseball since he debuted at 21 with the Kansas City Monarchs in 1930, and he was sure to savor the challenge as a competitor.1 But he had been out there for 11 innings, and his arm must be getting tired. Gibson had been on the bench the entirety of the game, and his appearance so late in the game as a pinch-hitter was most definitely intended to intimidate. Not that bypassing Gibson would ease the pressure — the next spots in the lineup were occupied by the great Raymond Brown and Cool Papa Bell.2 Nonetheless, Gibson was intentionally walked on four pitches.3 Like everything else involved with that unorthodox postseason, the odds were stacked against normalcy.

Since 1937 the Homestead Grays had split their home games between Pittsburgh and Washington.4 During the 1943 campaign they played roughly 22 games on 7th St in Washington, at Griffith Stadium,5 where local black fans enjoyed both the Grays and the Senators, though the latter only from an “unofficially” segregated right-field section.6 These were mixed in with dozens of games in Pittsburgh and along the East Coast as the Grays cruised to their second pennant in two years. Led by manager Candy Jim Taylor, they had the best lineup in black baseball, though their star, Josh Gibson, had been in and out of St. Elizabeth’s Hospital suffering from varying substance-abuse issues.7

The Grays’ opponents in the ’43 Series, the Birmingham Black Barons, were owned by Tom Hays and booked during the war years by Harlem Globetrotters promoter Abe Saperstein.8 They were managed by talent scout and former Harlem Globetrotters coach Winfield “Lucky” Welch. The Barons’ “hitting and fielding … blends as perfectly with the expert pitching as a rising sun on a pond of water and with just as picturesque results,” wrote an observer.9

Beginning in 1937, the annual playoff between the Negro American League and Negro National League champions had been a loose-knit affair arranged and scheduled by the teams themselves instead of a strong central office. Barons catcher Ted “Double Duty” Radcliffe had spent the entire season managing the Chicago American Giants, and had only made the Birmingham roster after regular catcher Paul Hardy had been drafted into military service.10 This was, according to NNL and NAL bylaws, against the rules. Cum Posey and Wendell Smith, both writing for the Pittsburgh Courier, voiced their (somewhat biased) opinion that such flouting of the rules would serve only to hurt the validity and character of the game.11 Radcliffe’s presence on the field only amplified the perception that the Negro Leagues were fit for raiding by the “Majors.”

Posey suggested that the converse would be nothing but profitable: “This attendance could be tripled if all those associated with Negro baseball became World Series minded.”12

Adding to the confusion, the multitude of games played at the end of September led to the September 24 game being referred to as the third or fourth game of the Series in varying press coverage. In fact, if it wasn’t for a last-minute schedule rearrangement by Clark Griffith of previously booked Griffith Stadium, the entire World Series might have been played outside the East Coast.13

No matter, whatever point in the Series it was, the game on the 24th proved to be the most exciting and pivotal of the Series, with reports of anywhere from 7,000 to 9,000 spectators in Griffith Stadium braving the bone-chilling weather to root for the Grays.14

Johnny Markham, who had a mean knuckleball,15 was on the mound for the Barons, and Roy Partlow for the Grays. While Partlow cruised, Markham made it through only one easy inning before things unraveled because of some less than stellar defense.

In the second, with Sam Bankhead and Vic Harris on base, Robert Gaston, who was filling in at backstop for the incapacitated Gibson, hit a sharp liner to center field. The runners both had a good jump and were circling toward home, forcing center fielder Felix McLaurin to force the throw to third in an attempt to catch Harris.16 The throw sailed over Hoss Walker’s head, igniting a scramble for the ball as neither catcher Radcliffe nor pitcher Markham had backed up efficiently.17 In the confusion, third was left uncovered as Gaston steamed into the base. When the ball arrived at third, no Birmingham player was there to field it and as it careened toward the outfield, Gaston trotted home.18

And that would be it, with the exception of a flurry of activity in the top of the sixth. Accounts vary as to when Grays pitcher Partlow injured his finger, with some saying a screamer off the bat of McLaurin in the fifth, and others a ball hit by Spearman doing the damage. Manager Jim Taylor gave his ace the benefit of the doubt and left him in, only to watch as Lester Locket made it on base safely with a single, and a run scored.19

Taylor, who had been involved with organized black baseball since 1909 and had played with Rube Foster, was too experienced to take any more chances. Despite a one-walk, five-hit performance, Partlow was replaced by Raymond Brown. Brown seemed destined to live up to his Hall of Fame credentials despite his age, only to watch shortstop Sam Bankhead throw wild and allow two unearned runs to score.20 After Brown got out of the inning with the score now 3-3, he shut down the Barons without a hit the rest of the game.

Birmingham’s ace, Johnny Markham, was equally defiant in the face of the Grays’ intimidating lineup.21 Despite the hiccup in the second inning, Markham had held his own. Birmingham skipper Welch had recognized his stuff and knew that if it weren’t for the sloppy fielding of his NAL champs, Markham would already be hitting the showers a winner. Instead, he was forced to ask his ace to intentionally walk black baseball’s number-one superstar and load the bases in the bottom of the 11th.

Sam Bankhead had opened the inning with a slap single to center field. Vic Harris followed with a dribbler up the first-base line that Sloppy Lindsay threw wild in an attempt to get Bankhead at second. The ball careened into center and the Barons were faced with runners at the corners and no outs.22

After Markham walked Gibson, Raymond Brown bunted up the first-base line. Lindsay fielded it cleanly this time and had no choice but to throw home instead of trying for second and an easy two. The ball arrived at the plate on time, but Radcliffe was unable to pivot and throw to first. The tie was preserved, but there was only one out.23

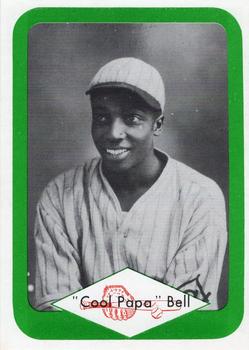

The tension was palpable as the fans seemed to momentarily forget the cold in the excitement of Cool Papa striding to the plate. With the infield playing in and all eyes on Vic Harris at third, Harris had options, and the Barons infield knew it — anything they could get their hands on would require quick diligence to hold him at third while getting that precious second out.

Bell, however, never gave them a chance. Markham threw whatever junk he had left, and Bell smacked a clean single between first and second. As the ball settled in right field, Vic Harris strolled home to the screaming cheers of the hometown fans.24

It would be a few more days before the Grays clinched the Series, beating the Barons soundly 8-4 in Montgomery, Alabama.25 As in years past, exhibition games featuring the NAL and NNL champs had been scheduled both during and after the Series — the most contentious being a game in New Orleans that would not be played due to miscommunication between promotor Alan Page and the front office of both Birmingham and the Grays, resulting in an outpouring of anger from organizers and fans alike.26

As the fans and sportswriters had made clear, the rising popularity of black baseball was hampered by such disorganization. If things weren’t improved in 1944, the whole enterprise would be in jeopardy.

Notes

1 Johnny Markham Baseball Reference Negro Leagues Page (baseball-reference.com/register/player.fcgi?id=markha000joh), last accessed March 31, 2019.

2 Art Carter, “Grays Win, 4-3, in 11th,” Baltimore Afro-American, October 2, 1943: 18.

3 Ibid.

4 Brad Snyder, Beyond the Shadow of the Senators: The Untold Story of the Homestead Grays and the Integration of Baseball (Chicago: Contemporary Books, 2003), 87.

5 “Record of Games Played by Homestead Grays 1943 Season — Up to and Including September 12th.” Undated press release in Art Carter Papers 1932-1988, (Box 170-18, Folder 17), Mooreland-Springarn Research Center, Howard University Libraries, Washington.

6 Snyder, 2.

7 John B. Holway, Josh and Satch: The Life and Times of Josh Gibson and Satchel Paige (Westport, Connecticut: Meckler, 1991) 165.

8 Rebecca T. Alpert, Out of Left Field: Jews and Black Baseball (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011).

9 “Fighting Black Barons Primed for Battles with Eastern Foes,” Pittsburgh Courier, September 4, 1943: 19.

10 Cum Posey, “Posey’s Points,” Pittsburgh Courier, October 2, 1943: 16.

11 Wendell Smith, “‘Smitty’s’ Sports Spurts,” Pittsburgh Courier, October 2, 1943: 16.

12 Posey.

13 Ibid.

14 Fay Young, “Bell’s Single in Eleventh Beats Barons,” Chicago Defender (National Edition), October 2, 1943: 11.

15 Frazier Robinson with Paul Bauer, Catching Dreams: My Life in the Negro Baseball Leagues (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1999) 39.

16 Young.

17 Carter.

18 Young.

19 “Grays Beat Barons, 4-3, in World Series: ‘Third Tilt Won in 11th on Line Single by Bell,” New York Amsterdam News, October 2, 1943: 20.

20 Young.

21 Carter.

22 Young.

23 Ibid.

24 Carter.

25 “Washington Grays Win Negro Title,” Washington Daily News, October 6, 1943: 48.

26 Hayward Jackson, “Failure to Play New Orleans Game Irks Fans,” Pittsburgh Courier, October 16, 1943: 16.

Additional Stats

Homestead Grays 4

Birmingham Black Barons 3

11 innings

Game 3, Negro League WS

Griffith Stadium

Washington, DC

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.