September 29, 1880: Metropolitan club opens new Polo Grounds with a win

The first professional baseball game played in Manhattan took place on September 29, 1880, between the Metropolitan Club of New York and the National Club of Washington. This late a date is remarkable. Organized baseball had arisen among New York clubs a quarter century previous, and openly professional baseball had been played for over a decade. So why did it take so long to reach Manhattan? The explanation lies in geography and economic and social history.

The geography of New York City (meaning, in this era, the island of Manhattan) tended against professional baseball within its limits. The city grew from the south end, gradually spreading up the island. Within the developed area there were no good locations for a professional ball ground, for the simple reason that any suitable lot could be more profitably developed for other purposes. There were suitable lots above the line of development, but inadequate transportation infrastructure for spectators to easily get to them. It was cheaper and easier to take a ferry, crossing either the Hudson River to Hoboken or the East River to Brooklyn.

Many clubs based in New York City played in Hoboken or Brooklyn. The first ballfields enclosed by a fence – a necessary condition for charging admission – were constructed in Brooklyn. This had the proper balance of enough population density (both those residing in Brooklyn and visiting from New York) to support large paying crowds, with land values low enough that baseball exhibitions were an economically rational use of the land. The most prominent New York nine was the Mutual Club. It played in Hoboken in the amateur era and then moved to the Union Grounds in Brooklyn in the professional era.

Baseball in Manhattan was further delayed by the general economic Depression of 1873-1879. Indeed, professional baseball went into general decline. The National League, founded in 1876, had a high turnover of club failures in its early years, with vacancies filled by bringing in outside clubs. The nadir was the summer of 1880. The National League had its full complement of eight members, but there were only two other fully professional clubs in existence.

This general decline does not explain why such a large metropolis as New York could not support a professional club. The Mutuals collapsed late in the 1876 season. The Hartford club stepped in and played the 1877 season in Brooklyn, but they too failed and were not replaced. A similar process occurred in Philadelphia, leaving the two largest metropolises in the country without professional – much less major league – baseball clubs. Their long histories with baseball worked against them. They both had baseball establishments, which were inflexible and often corrupt. Advances in both playing and business techniques occurred elsewhere, leaving the New York establishment unable to compete. Professional ball’s absence acted like a farmer leaving a field fallow, giving it time to renew itself. This allowed a new generation, and the more forward-looking of the previous generation, to create a new establishment unburdened by the past.

The baseball recovery began late in the season of 1880. In August the Nationals and the Rochester Club scheduled a series of games in Brooklyn. This would prove visionary, but the decision was one of desperation. Recent history had shown the metropolis to be a baseball dead zone, but both clubs were in dire straits and prepared to try anything. They played three days in a row, beginning Wednesday August 11. The first game drew only three or four hundred spectators, but attendance increased with each successive game.

This caught the attention of the dormant New York baseball community. Several respectable nines sprung up, recruiting from the ample supply of inactive players. Most were ephemeral organizations, essentially pick-up teams that wouldn’t outlast the season. Two men, however, saw potential for something more substantial.

These were John B. Day, a cigar manufacturer, baseball fan, and unaccomplished player, and James Mutrie, an experienced professional player and manager, if not at the top level. Day provided the capital and Mutrie the baseball know-how. Day’s genius was in recognizing that he was in the right place at the right time. Baseball was reviving in New York, with no established club holding the public’s loyalty. Furthermore, the time had come for professional ball to be played on Manhattan. Railroad infrastructure had developed such that paying spectators could easily reach a site beyond the edge of development.

An eminently suitable parcel was available immediately beyond the northern end of Central Park, and easily reached by no fewer than four rail lines. This property was owned by James Gordon Bennett, son of the founder of the New York Herald. He was a member of the Manhattan Polo Association, which had been using it for several years. Day leased the ground, its use to be divided between the polo club, with two days a week, and Day’s new Metropolitan Baseball Club, with four days. Sunday, of course, was off limits, both being respectable organizations.

By acting quickly to set up a ball club on a permanent basis, Day could gain control of the New York market. The venture came with risk. Setting up the club on a permanent basis meant investing capital in salaries and real-estate improvements. Should the baseball revival prove illusory, this capital would be lost.

The improvements were substantial, with facilities not only for polo and baseball, but for track and field sports (“athletics” in the vocabulary of the day) and football, with a grandstand capable of holding a thousand spectators and encircled by a fence to ensure payment for entry.

Mutrie recruited the new Metropolitan team as the Polo Grounds were being prepared, rapidly putting together a credible nine. On September 15 they opened a series of warm-up games in Brooklyn and Hoboken against some of the new ad hoc collections, winning eight of nine games, most of the easily.

The occasion of the opening game of the new Polo Grounds called for more substantial competition than a glorified pick-up team. This was the National Club of Washington. The Nationals were an established team, the second of that name. The original Nationals had been the premier Washington club in the 1860s, most famous today for their being the first eastern club to tour the west (meaning what we today call the Midwest) in 1867. They faded away in the early professional period. The second Nationals were founded in 1877. This was an inauspicious time to be getting into professional baseball, and it is a testament to their management that they rode out the darkest years. Their prospects were excellent in the fall of 1880. They had good reason to believe that they would be inducted into the National League for 1881 and were making the investments to be competitive at that level. They provided the Metropolitans with the perfect balance. They were decent competition while still being beatable, still fielding their lineup of 1880.

The afternoon of the game opened well. Some 2,000 to 2,500 spectators showed up. While tiny by modern standards, and small by the standards of just a few years later, this was a very good crowd in 1880. Matters took a turn for the worse when the Nationals were late. Play was advertised for 3:30. By 4:00 some of the crowd was beginning to leave and a scrub game was being organized. The Nationals finally arrived, and play was called at 4:20 with the Metropolitans batting first. The game was everything that could be asked for given the late start. The leadoff batter opened with a triple and scored two outs later on a ground ball through the second baseman’s legs. The score was tied 2-2 after two innings. The Metropolitans scored two runs in the top of the fifth, and the game was called on account of darkness in the sixth, for a 4-2 victory for the home club.

This victory was followed by two more over the Nationals the next two days. These early victories set a good tone. It was fortunate that they got them in early. The end of September closed out the National League season and opened the October barnstorming season. The following Monday the decidedly mediocre Worcester club came into town and beat the Metropolitans 7-3. The Metropolitans would go on to win against National League clubs about one game in three. They weren’t yet ready for the big time, but their future was bright. (The Nationals faced a bleaker future. The National League chose the new Detroit club over them, and proceeded to find a thin excuse to steal away the Nationals’ best players. This broke the club, and it finally collapsed the following summer.)

The new Polo Grounds would prove a financial bonanza. The Metropolitans could limit their travel, and their travel expenses, and let other teams come to them, to large crowds. They managed this for the next two seasons. This strategy had run its course by 1883. Both the National League and the new American Association courted Day, and he managed the neat trick of playing both sides and getting a franchise in both leagues.

With two franchises and only one team, he signed the players of the defunct Troy team en masse, combined the Metropolitan and the former Troy players into one pool, and divided them up again, assigning the better half to the National League club. He sold the American Association half a few years later, and it lasted only a few years beyond that. He kept the National League side for a decade, until he succumbed to a later economic depression and was forced to sell.

The National League team was, of course, the Giants. The American Association side kept the old “Metropolitan” name. Some modern moderns dismiss the connection between the Metropolitans of 1880 and the Giants of today because of this. This is misguided. The Metropolitans of 1880 fathered the Giants every bit as much as they did the Metropolitans of 1883. Or better, to choose a different biological metaphor, they underwent mitosis, splitting into two. The 1880 season was a watershed year in professional baseball, with not only its entry into Manhattan but the creation of one of its storied franchises.

Photo credit

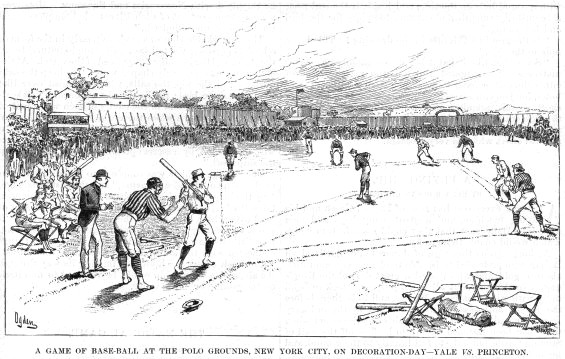

The earliest known image of Polo Grounds I in New York, from a Yale-Princeton baseball game in 1882. Originally published in Harper’s Young People, v. III, 1882. (PUBLIC DOMAIN)

Additional Stats

New York Metropolitans 4

Washington Nationals 2

Polo Grounds

New York, NY

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.