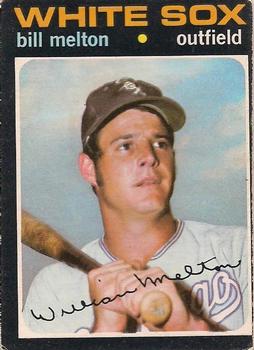

September 30, 1971: Bill Melton becomes first White Sox player to lead AL in home runs

Over their first 70 seasons, Chicago White Sox fans saw some historic moments. Early on, they won two World Series, in 1906 and 1917. Two years after the latter, they suffered the most infamous Series loss ever, in 1919, when eight of their players took money to throw the Series to Cincinnati. The team’s fans had also seen some all-time greats: Joe Jackson, whose participation in the 1919 scandal has kept him out of the Hall of Fame; Luke Appling, a two-time batting champion who is in the Hall of Fame; pitcher Ed Walsh, who is also in the Hall of Fame and is one of only two post-nineteenth-century pitchers to win 40 games in a season.

Over their first 70 seasons, Chicago White Sox fans saw some historic moments. Early on, they won two World Series, in 1906 and 1917. Two years after the latter, they suffered the most infamous Series loss ever, in 1919, when eight of their players took money to throw the Series to Cincinnati. The team’s fans had also seen some all-time greats: Joe Jackson, whose participation in the 1919 scandal has kept him out of the Hall of Fame; Luke Appling, a two-time batting champion who is in the Hall of Fame; pitcher Ed Walsh, who is also in the Hall of Fame and is one of only two post-nineteenth-century pitchers to win 40 games in a season.

One thing the White Sox fans did not see in those years was a home-run title for the home team.

For that, they had to wait until 1971, when Bill Melton snatched the crown from Reggie Jackson and Norm Cash on the final day of the season. To win it, Melton had to pull himself out of a nearly monthlong slump and slug three round-trippers over the final two days to claim the title by a single homer, 33 to 32.

Melton, who turned 26, was in his third full season with the White Sox. The previous year he’d become the first player in franchise history to hit 30 home runs when he slugged 33, sixth best in the league. (Frank Howard was tops with 44.)

Despite that, 1970 had sometimes been a struggle for him.

In his first two dozen games as White Sox third baseman, he committed 12 errors, six of them in a stretch of four games. On the last, he misjudged a popup that broke his nose.1 In late June manager Don Gutteridge shifted him to right field. Melton publicly expressed unhappiness: “I just don’t like it. … Besides, I think it’s affecting my hitting, and I lose my concentration out there. You don’t feel like you’re in the ballgame.”2

His stats bear this out. When Gutteridge moved him, Melton was hitting .295 with an .825 OPS. After the move to right, he hit only .239 over his next 71 games although his OPS was a nearly identical .822. He also tied two ignominious records: In July, he tied a major-league mark that still stood in 2018 when he struck out seven times in a doubleheader. He also tied the American League record for fanning in 11 consecutive at-bats between July 23 and July 28.

Coming into 1971, however, Melton and others expected a better year. One difference: The White Sox had fired Gutteridge the previous September and new manager Chuck Tanner had shifted Melton back to third, after giving him a few tips he thought would help his fielding. (They apparently did. At third in 1970, his fielding average, .926, ranked lowest of any player with at least 50 games at the position. In 1971, it was .968, tied for fourth best. In addition, he led AL third basemen in range factor.) The Sporting News said that with Melton back in the infield, the team was stronger than it was without him there.3 One Chicago sportswriter went so far as to predict that Melton would win the AL home-run crown.4

Early on, it did not seem Melton would fulfill that forecast. While he homered in the White Sox’ first two games (an April 7 doubleheader), he didn’t hit his third until May 15. By May 31 he had only six. Meanwhile, Jackson had 10 and Cash 11.

In June, however, Melton got hot, slugging a dozen home runs, and ended that month tied for the league lead with Tony Oliva at 18. His performance earned him his only career All-Star selection. While he cooled off, hitting only nine home runs combined in July and August, as September began his 27 total round-trippers tied him for the league lead with Cash and Reggie Smith.

But if Melton was cool in August, he was cold for nearly the entire final month. From September 1 to 28, he hit only .204 with three home runs. However, his competitors for the crown had suffered their own power outages. While Jackson hit 15 home runs combined in August and September, he hit only one in July. From August 8 to September 24, Cash hit only five. (Smith hit only three for all of September, ending the year with 30.)

As play ended on September 28, both Jackson and Cash had 32 home runs while Melton had 30. The next day Tanner sought to boost what was perhaps an outside chance for Melton to win the crown by shifting him to leadoff from his customary number-four spot to give him an additional at-bat.5 Melton responded by slugging two round-trippers in a 2-1 White Sox win over Milwaukee. When neither Cash nor Jackson homered that day, Melton was assured of at least a tie for the crown, since both of their seasons were over.

After the game, Melton said that his two long balls were due to several factors: “I spread myself out more in the batter’s box, moved closer to the plate, choked two inches on the bat and was using a heavier bat. … I was going for the home run. I have been for three weeks.”6

This set up the season finale and Melton’s last shot for sole claim on the title.

The game itself meant nothing in the standings. At 78-83, the Sox had clinched third in the division while their opponent, Milwaukee, 69-91, had clinched last.

The Brewers sent rookie right-hander Bill Parsons (13-16) to the mound while the White Sox countered with southpaw Jim Magnuson (1-1) who, although in his second season, was still officially a rookie since he’d thrown only 44⅔ innings in 1970. For 1971, he’d been up and down between Chicago and Triple-A Tucson.

In his first at-bat, Melton grounded to short in a scoreless first inning. Magnuson set down the Brewers in order in the first two innings, while the White Sox went up 1-0 in the bottom of the second when Tony Muser tripled and Chuck Brinkman singled.

Melton batted again leading off the third. Because it was the only significant event of the contest, the Tribune devoted the lede in its game account to Melton’s swing on a 2-and-2 count:

“Bill Melton drove his bat into a fastball and the scene in Comiskey Park … froze as if waiting for a picture to be snapped.

“The ball soared in a low, screaming arc toward the left center field lower deck. As it gathered momentum … the freeze was shattered by the sudden realization that the . . . third-base star had made the final day … one of the most memorable in the 71-year existence of the club.

“When the ball landed in the third row of the lower deck, Melton became the White Sox’ first American League home run champion.”7

Melton, not surprisingly, was ecstatic, saying, “I didn’t know how to touch the bases, I was so excited. … The thing that amazes me is that I was trying to hit home runs the last two days and I hit ’em.”8

As he reached the dugout after rounding the bases, giving the White Sox a 2-0 lead, he tossed his helmet into the crowd, who kept cheering, bringing him back to acknowledge their ovation.

In the top of the fourth, Melton went out to third, but after the first pitch Tanner replaced him with Walt Williams so Melton could have another ovation as he left the field.9 Later, the fan who caught the home-run ball gave it to Melton, who reportedly paid him $50.10

The White Sox held their 2-0 lead through eight innings, as Tanner sent a series of rookies to the mound for two innings each (after Magnuson came Rich Hinton, Don Eddy, and Denny O’Toole) until Stan Perzanowski finished in the ninth. He allowed the Brewers their only run. Jose Cardenal singled and John Briggs and Dave May reached on White Sox errors on successive plays, loading the bases. After fanning Andy Kosco, Perzanowski walked Darrell Porter, forcing in a run, before closing out the 2-1 victory. Hinton (3-4) got the win, while Parsons (13-17) took the loss. Perzanowski earned his first career save.

That year was the high point of Melton’s career. In November he fell off a ladder, hurting his back. By late June 1972, the pain was so bad that he had season-ending surgery, and finished with just 7 home runs. That season, too, Dick Allen eclipsed Melton’s short-lived White Sox home-run record when he led the league with 37.

Melton played three more seasons in Chicago, averaging only 18.4 home runs a year. In 1975, when he hit .240 with 15 home runs, the fans who’d celebrated him four years earlier were booing him and he asked for a trade.11 The White Sox obliged, sending him to the Angels. After a season with California and one in Cleveland, he retired.

Sources

https://retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1971/B09300CHA1971.htm.

https://baseball-reference.com/boxes/CHA/CHA197109300.shtml.

Notes

1 Jerome Holtzman, “Agony of Errors … Ordeal of Chisox’ Melton,” The Sporting News, May 23, 1970: 5.

2 George Langford, “White Sox’s Melton Is Unhappy; Prefers Third Base to Outfield,” Chicago Tribune, June 30, 1970: 32.

3 C.C. Johnson Spink, “Spink’s Forecast: Orioles and Dodgers to Win,” The Sporting News, April 10, 1971: 5.

4 “Repeat of 1970? That’s What Poll Says,” Chicago Daily Herald, April 5, 1971: 2-3.

5 George Langford, “Melton A.L. Home Run King,” Chicago Tribune, October 1, 1971: 63.

6 Ibid.

7 Langford, “Melton A.L. Home Run King.”

8 Ibid.

9 Ibid.

10 Ibid.

11Jerome Holtzman, “Boos Stir Melton to Hope for Trade,” The Sporting News, November 1, 1975: 23.

Additional Stats

Chicago White Sox 2

Milwaukee Brewers 1

Comiskey Park

Chicago, IL

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.