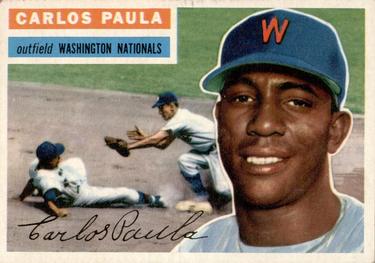

September 6, 1954: Carlos Paula integrates the Washington Senators

The game appeared to be merely the first in a meaningless, end-of-the-season doubleheader between two teams that many weeks earlier had been eliminated from the 1954 pennant race. The sixth-place Washington Senators trailed the league-leading Cleveland Indians by 39 games and the Philadelphia Athletics were even further out of contention: 51½ games back. However, as the Senators took the field the tiny crowd of 4,865 immediately recognized the significance of the game. Trotting out to left field was Carlos Paula, who was about to become the first Black ballplayer to play for the Senators. Seven years after Jackie Robinson had broken the color barrier in baseball, the Senators on this day became the 12th franchise to do the same.

Paula’s appearance in a Senators uniform was the end of a long journey for team owner Clark Griffith. For three decades he had eagerly signed black Cuban players to professional contracts but staunchly opposed allowing them to play major-league baseball. Through the years he had offered numerous rationalizations intended to keep baseball segregated. He argued that black players would be subjected to vicious racist epitaphs and that mixing black and white fans would lead to violence.1 He also warned that integrating baseball would kill the Negro Leagues, thus significantly reducing the number of African-Americans playing professional baseball. Instead, a vibrant, profitable Negro League would be better for African-Americans.2

Underlying Griffith’s opposition were concerns about his own revenues. Griffith Stadium was very accessible for the local black community. For years Griffith had leased his ballpark to Negro League teams. He had a particularly profitable relationship with Cum Posey and the Homestead Grays.3 However, by 1954 Griffith recognized that the Negro Leagues were rapidly losing their viability. He calculated that his long-term revenue interests would be better served by including black players on the Senators roster.

A product of the Cuban leagues, Paula was one of more than three dozen Cubans signed to a Senators contract by legendary scout Joe Cambria. The young Cuban first worked out for Cambria in 1951. By the following spring he was playing in the Senators farm system. Success with the Decatur Commodores in the Mississippi-Ohio Valley League and the Paris Indians in the Big State League brought Paula to the attention of key figures in the Senators organization. By 1954 he was one of two Cubans (Angel Scull was the other) whom many expected to be the first black Senator.

Senators manager Bucky Harris watched Paula intently during spring training in 1954. “He can whack that ball,” Harris said. “He has size and gets some beautiful extra leverage to his swing. And he isn’t fast simply for a big man. He’s fast for a man of any size.”4 Paula had been one of the Senators’ last spring-training cuts. Assigning him to Charlotte in the South Atlantic League, Harris wanted him to work on a hitch in his swing and to develop more discipline at the plate. It was his power that particularly impressed Harris. On a team in need of more punch, the big Cuban, who was “the rawest of rookies, but obviously a brute for muscle,” might potentially fill a team void.5

The day’s first game started quietly. In the first inning both teams put a runner on base via a walk but neither was able to do more than that. Philadelphia went in order in the second. Paula led off the second for the Senators. At the plate, he was an imposing figure, 6-feet-3 and “built like a blacksmith.”6 In his first major-league at-bat, he struck out. Then his teammates used two singles and a sacrifice to push across the game’s first run.

Two innings later, Paula helped the Senators break the game open. With two outs and a runner on first, the top of the Washington order strung together two singles, a walk, and a three-run triple by first baseman Mickey Vernon. Pete Runnels followed Vernon with a walk, putting runners on first and third for Paula. The Senators first African-American player scorched a double to left-center field, scoring both runners. Paula’s first major-league hit also drove the Athletics pitcher, Arnie Portocarrero, from the mound. He was replaced by Marion Fricano, who struck out right-fielder Jim Lemon to end the inning.

Neither team was able to score during the next three innings. The Senators were limited to an infield single and a walk in the fifth. In the sixth Paula collected his second hit, a bases-empty, two-out single to center. Meanwhile the Washington pitcher, Johnny Schmitz, dominated the Athletics, retiring all nine hitters he faced.

In search of his 10th win, Schmitz came into the game with an impressive 2.81 ERA. The 1954 season was a comeback season in many ways for Schmitz. After returning from a stint in the Navy from August 1942 until January 1946, he had been a reliable starting pitcher with an impressive ERA through the 1950 season. Twice during those years, he had been selected to the American League All-Star team. However, the previous three seasons had been a different story. He had some arm problems, his ERA jumped by more than a run per game, he had won a total of only seven games and had been bounced around from team to team through trades. The 1954 season offered a restart for Schmitz. With his ERA back below 3.00, he settled in as one of the Senators’ regular starting pitchers. Reaching the 10-win plateau became a notable milestone in Schmitz’s comeback journey.

The Athletics finally got to Schmitz in the eighth. Right fielder Joe Taylor walked to open the inning and went to third on a single by Eddie Joost. One out later Lou Limmer, pinch-hitting for relief pitcher Fricano, lifted a fly to Paula in left field, scoring Taylor. After another walk, Philadelphia’s half of the inning ended on a fly ball to Lemon in right field. Schmitz’s shutout was gone but his quest for win number 10 was still very much alive.

In the bottom of the inning, the Senators got the run back plus interest. With one out, the new Philadelphia pitcher, Sonny Dixon, walked Tom Umphlett, who had come into the game in the seventh as a defensive replacement for Jim Busby in center field. Mickey Vernon followed with his 20th and last home run of the season. The reigning American League batting champion, Vernon was not known for his power. This season was the only one in which he reached the 20-home-run level.

The ninth inning was another three-up three-down inning for Schmitz. Allowing only three hits and one run, he had one of his better performances of the season.

Despite a 3-2 loss in the second game, for the Senators and several of the team’s players, the day was a success. For Johnny Schmitz it was his 10th victory and seemed to confirm his comeback. Mickey Vernon would remember the day because he hit his 20th home run of the season. But far more important was the debut of Carlos Paula in left field. With him in the lineup, the Senators entered a new era in the team’s history, becoming the 12th major-league team to open a door to African-American players.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author accessed Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, and SABR.org.

Notes

1 Neil Lanctot, Negro League Baseball: The Rise and Ruin of a Black Institution (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1996), 220.

2 Lanctot, 234.

3 Lanctot, 249, 267.

4 “Harris High on Ex-Paris Indian Paula,” Paris (Texas) News, March 17, 1954: 9.

5 Red Smith, “Views of Sport,” Rocky Mount (North Carolina) Telegram, March 14 1954: 32.

6 “Cuban Rookies May Crack Sen’s Roster,” Daily Independent (Kannapolis, North Carolina), March 12, 1954: 5.

Additional Stats

Washington Senators 8

Philadelphia Athletics 1

Game 1, DH

Griffith Stadium

Washington, DC

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.