September 9, 2013: Pittsburgh Pirates finally end 20-year losing drought

Despite the promise of the previous two seasons, by 2013 Pirates fans were more jaded than ever. There had always been the hope that the losing-season streak, now 20 years long, inevitably had to end at some point. Now, after back-to-back late-in-the-season collapses, there was a feeling that nothing would end the streak. But just as Pirates fans were finally ready to abandon all hope, it finally happened. The Pirates’ next winning season took so long that Doug Drabek and Andy Van Slyke’s sons would be playing major-league baseball by the time it finally died. It came in a game that on paper was nothing all that interesting. There were no diving, game-saving catches or ninth-inning, base-clearing home runs, just some really solid pitching. Even the celebrating was all but nonexistent. But to Pirates fans, it was quite possibly the greatest baseball game since Bill Mazeroski’s home run won the 1960 World Series. When Sid Bream slid into home plate in Game Seven of the 1992 NLCS, there were tears all over Pittsburgh. Almost 21 years later, there would be tears flowing again but these were tears that finally washed away all those years of frustration, heartbreak, bitterness, and embarrassment.

Despite the promise of the previous two seasons, by 2013 Pirates fans were more jaded than ever. There had always been the hope that the losing-season streak, now 20 years long, inevitably had to end at some point. Now, after back-to-back late-in-the-season collapses, there was a feeling that nothing would end the streak. But just as Pirates fans were finally ready to abandon all hope, it finally happened. The Pirates’ next winning season took so long that Doug Drabek and Andy Van Slyke’s sons would be playing major-league baseball by the time it finally died. It came in a game that on paper was nothing all that interesting. There were no diving, game-saving catches or ninth-inning, base-clearing home runs, just some really solid pitching. Even the celebrating was all but nonexistent. But to Pirates fans, it was quite possibly the greatest baseball game since Bill Mazeroski’s home run won the 1960 World Series. When Sid Bream slid into home plate in Game Seven of the 1992 NLCS, there were tears all over Pittsburgh. Almost 21 years later, there would be tears flowing again but these were tears that finally washed away all those years of frustration, heartbreak, bitterness, and embarrassment.

The 2013 season started dreadfully, five losses in the first six games, and Pirates fans almost felt relieved that they wouldn’t have to suffer through the tease of a winning record that the previous two seasons had provided. And despite the stigma that came with losing season number 20, it almost came as a relief. Number 20 was over and what difference would 21 make? However, as painful as they were, those two mirage-like seasons were really setting up the actual winning season that was finally coming. During the 2011 and 2012 seasons (Clint Hurdle’s first two as the Pirates manager), the team began to perfect its “torture-ball” style of winning, grinding out a few runs with a meager offense while frustrating teams with stellar pitching, keeping its opponents to a few runs a game. The Pirates didn’t collapse the previous two seasons because of some otherworldly curse. They just needed to sustain their winning for a full season. Besides, these players adored one another and their respect and love was infectious.

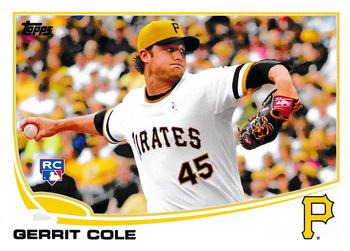

The starting pitching staff was dominant in 2013, with veterans A.J. Burnett and Francisco Liriano doing some of their best work in years. By mid-July, Liriano had an ERA of 2.00 and a record of 9-3. He would go on to win the National League Comeback Player of the Year Award. Under the tutelage of Burnett, young lefty Jeff Locke went from barely making the starting rotation out of spring training to a surprising All-Star bid. In June, the Pirates called up a former number-one draft pick, right-hander Gerrit Cole. His first appearance couldn’t have been scripted better. The reason for the success of Cole, Locke, and Charlie Morton was due in large part to the pitch calling of catcher Russell Martin, who came even better than advertised. Under his tutelage, the starting rotation went from 13th in the league in ERA to second. Meanwhile, Andrew McCutchen began what would eventually become his MVP season, becoming the first real homegrown national baseball celebrity Pittsburgh had seen since Barry Bonds. McCutchen was in his fifth year and unlike most of the team had been part of that 20 years of losing.

But the real key to the Pirates success in 2013 was the Shark Tank. Closer Jason Grilli, Mark Melancon, Tony Watson, Justin Wilson, Jared Hughes, Bryan Morris, and Vin Mazzaro comprised “the best bullpen in baseball,” according to Tigers manager Jim Leyland.1 They frustrated and eventually terrified opposing teams like sharks sensing blood in the water, earning their nickname. Under the suggestion of the electric Grilli, management even installed a live, working shark tank in the clubhouse. The Pirates bullpen was so dominant that they had reduced games to six innings. If the Pirates had a lead by the time the game was official, it was usually over. Their record at midseason in such games was 40-2.

The National League Central Division was poised to place three teams in the playoffs. By late August the first-place Pirates were a staggering 24 games over .500. The Cardinals started performing better and the Pirates would soon be playing catch-up, while also fighting off the Cincinnati Reds.2 Amid the wins, number-one Power Rankings, and Sports Illustrated covers, the team was dealing with unparalleled pressures. While they had to play with the normal, everyday anxiety that comes with a playoff stretch run, being a Pirate also meant you were inundated with nonstop locker-room questions about the slide, the 20-year losing streak and now “the collapse” or “the swoon” or whatever you wanted to call what happened in August the last two years.

Closer Grilli might have summed it up best: “We weren’t a part of all those 20 years, a lot of us, we have nothing to do with that. But we have everything to do with fixing it.”3

Fortunately for the Pirates, it was going to take the biggest collapse in baseball history to guarantee a losing season in 2013. By September, the Pirates were still rolling and for the first time in 20 years the words “Pirates” and “playoffs” were spoken in the same sentence. But one number was on the minds of every fan in Pittsburgh, .500. The city was going wild, Jolly Rogers were flying, PNC was rocking, repeatedly selling out. But for long-suffering Pirates fans, until it was mathematically impossible for the team to finish with a losing record, no one was ready to celebrate anything.

The streak finally came to an end on September 9, 2013. The Pirates were playing the first in a three-game series against the Texas Rangers in Arlington. After ensuring at least a .500 finish in Milwaukee the previous week, they lost their next four games. This small, innocuous losing streak was just enough to rattle the nerves of fans who actually thought the Pirates might drop their remaining 20 contests.

The game saw Rangers ace Yu Darvish take on Cole. Ironically, it was the rookie Cole, who had never been on a losing Pirates team, who finally brought the team that coveted win. It was the kind of game the Pirates had been winning all season, just enough offense to complement nearly perfect pitching. Cole and Darvish went back and forth through six innings trading strikeouts and 1-2-3 innings, slowly driving Pirates fans crazy. In the top of the seventh, the dam finally broke. Marlon Byrd hit a two-out double. Pedro “El Toro” Alvarez followed with a run-scoring double to deep center field, giving the Pirates one of the single most important RBIs in the history of the franchise.

Thanks to Cole and eighth-inning man Watson, the Pirates held their tenuous 1-0 lead going into the bottom of the ninth. Pirates fans held their breath as Melancon, filling in as closer for the injured Grilli, came in. Every pitch was tortuous. And when Adrian Beltre grounded a single to left field with two outs, it seemed as if the streak would literally never end. But with a routine groundout by A.J. Pierzynski, Melancon finally shut the door and just like that it was all over. It was win number 82. And despite celebrations all over Pittsburgh, there was no champagne popped in the clubhouse, no celebrating by the team. Hurdle didn’t even address the team after the game. It was as if they hadn’t realized what they had done. You couldn’t blame the night’s winning pitcher for possibly not fathoming the significance of the game, and what he had done that night for the city of Pittsburgh. Cole was two years old when the Pirates lost Game Seven of the 1992 NLCS. But the explanation for the muted celebration was clear. This team had not lost all those years – the franchise had, and the fans had. This was not the team’s celebration. This was Pittsburgh’s.

Only second baseman Neil Walker, the Pittsburgh kid, knew what the fans knew, that this was one of the most significant games in franchise history: “[A]s a fan, that number has some significance, yes. To the other 24 guys, I don’t think it holds that much weight.”4

You can’t blame the team for barely acknowledging the win. But for the fans and for the city, it was a 20-year sigh of relief. It put 20 years of misery to bed. It wasn’t just a baseball game. It was the end of one of the most miserable chapters in the history of Pittsburgh sports and the birth of a new one.

This article appears in “Moments of Joy and Heartbreak: 66 Significant Episodes in the History of the Pittsburgh Pirates” (SABR, 2018), edited by Jorge Iber and Bill Nowlin. To read more stories from this book at the SABR Games Project, click here.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author relied on the box-score and play-by-play account at Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org.

https://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/TEX/TEX201309090.shtml

https://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/2013/B09090TEX2013.htm

Notes

1 Lee Jenkins, “The Bucs Start Here,” Sports Illustrated, September 9, 2013.

2 Pittsburgh was a season-high four games in front on August 10 before St. Louis started chipping away at the Bucs’ lead.

3 Jenkins.

4 Jenkins.

Additional Stats

Pittsburgh Pirates 1

Texas Rangers 0

Globe Life Park

Arlington, TX

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.