1918 Red Sox: Spring Training

This article was written by Bill Nowlin

This article was published in 1918 Boston Red Sox essays

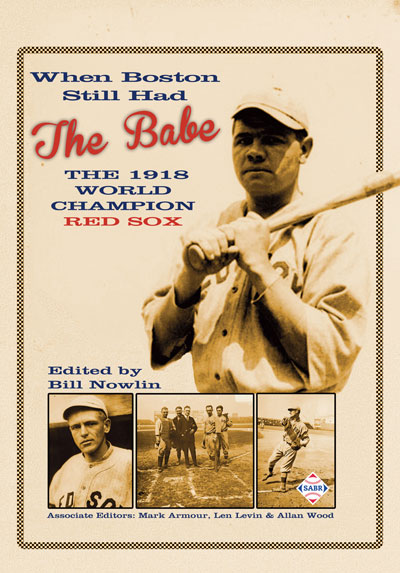

Frazee kicked off the new year making another move, again with Connie Mack’s Athletics, trading players to be named later for first baseman Stuffy McInnis. Mack termed the deal a “near-gift,” letting McInnis go to the team where he wanted to play even though he could have sold him for more than $25,000. Mack later selected Larry Gardner, Tillie Walker, and Hick Cady. The first player to sign with the Red Sox for 1918 was pitcher Babe Ruth. He inked a contract for $7,000 and talked about the possibility of winning 30 games (he was 23-12 in 1916).

Frazee kicked off the new year making another move, again with Connie Mack’s Athletics, trading players to be named later for first baseman Stuffy McInnis. Mack termed the deal a “near-gift,” letting McInnis go to the team where he wanted to play even though he could have sold him for more than $25,000. Mack later selected Larry Gardner, Tillie Walker, and Hick Cady. The first player to sign with the Red Sox for 1918 was pitcher Babe Ruth. He inked a contract for $7,000 and talked about the possibility of winning 30 games (he was 23-12 in 1916).

Towards the end of January, the Red Sox received word that Jack Barry would not be relieved from Navy duties for at least several months and was effectively lost for the season. Frazee again approached Bill Carrigan, with no success. On February 11, Ed Barrow was named as Jack Barry’s replacement as manager of the Red Sox. One of Barrow’s first pronouncements was that players would be prohibited from bringing their wives to spring training. Former Cubs star infielder Johnny Evers was hired as a coach, possible second baseman, and a “general strategy man.”1

Assembling a team was far more difficult than usual, given the number of players who were either gone to service or likely to be called. Barrow and Frazee had to constantly consider the depth of their roster and the replacements that could be brought to bear if this player or that player left for war-related work or to enlist in one of the service branches. Hanging over it all was the question as to whether the season itself might be curtailed at some point. Even as late as early March, the Sox roster was – to put it mildly – a little unsettled. It wasn’t exactly clear who might play second base and Barrow was considering playing first baseman Stuffy McInnis at third base. Other teams faced similar situations.

On March 8, the Red Sox left for spring training in the Ozarks, returning again to Hot Springs, Arkansas. A snow storm caused a delay of several hours in the trainyard outside Buffalo, and the Sox party missed their connection, costing them the first full day of practice. Soldiers on board the train sought out conversations with a gregarious Babe Ruth. The party heading south also included team secretary Larry Graver, attorney Thomas Barry, trainer Dr. Martin Lawler, and scout Billy Murray.

On March 11, Barrow met with his charges and “made it plain to them in a 15-minute talk that discipline more rigid than has ever been exercised before” would be a feature of the camp and throughout the season. No player was to be seen in the breakfast room after 9:30 in the morning. Moreover, poker was too be “confined strictly to the 10-cent variety and all games must end promptly each night at 11 o’clock.” The same rules applied to newspapermen, rooters, and others associated with the team. Not one player failed to conform the first day; two who worked out so intently they had to be told to end their day were Johnny Evers and Babe Ruth. After three hours of working out, the players walked the two miles back to the hotel. “Barrow refused to allow his men the luxury of a ride either to or from the park.” [Boston Post, March 12 and 13, 1918] As for Barrow, he had cut a bit of a stern image sitting in the bleachers and watching the men work out without saying a word. Harry Frazee was in town and finalized contracts with Sam Agnew and Carl Mays. A couple of days later, Barrow decided to drop mountain climbing from the exercise program; only if it was too wet to work out on the ballfield would the players be compelled to take mountain hikes.

Early in camp, a strange thing happened: despite some initial nervousness, 18-year-old prospect Mimos Ellenberg of Chuckey, Tennessee (some accounts say Mosheim), who Ed Barrow had proclaimed “may be another Hornsby,” impressed the Red Sox so much that they wanted to sign him. They couldn’t find him; he simply disappeared. It was later determined he’d become quite ill and, come March 17, he was sent home.

On March 16, several more of the squad turned up in town: Everett Scott, Amos Strunk, Fred Thomas, George Whiteman, and Paul Smith. Dick Hoblitzell arrived on the 19th – and four days later Ed Barrow named him as team captain. Dutch Leonard turned up on the 21st. McInnis was working out at third base, fielding bunt after bunt, while Fred Thomas “ostensibly recruited as a third sacker, is developing into a likely second baseman.” Pitcher Rube Foster said he wanted more money, then found Frazee telling him not to bother coming to Hot Springs unless he was to pay his own way, and was ultimately traded (on April 1) to Cincinnati for Dave Shean.

The first exhibition game came on Sunday, March 17 and Red Sox batters bombed Brooklyn pitching for 16 hits at Majestic Park, and won 11-1. Babe Ruth hit two home runs for the 2,500 assembled, matching his total for the entire 1917 regular season. It was one of only two games the Red Sox played in their Hot Springs home. As it happened, both the Brooklyn Robins and the Red Sox trained at Hot Springs in 1918, Brooklyn working out at Whittington Park. The two teams played 11 games, with Boston winning seven. After six days of workouts in the “Valley of the Vapors”, the two teams played another couple of games and then took their show on the road and proceeded to play five games at Little Rock, before heading on to three cities in Texas, as well as New Orleans, Mobile, and Birmingham.

Just a few days after the first game, however, there was a bizarre incident that could have ended the team’s pennant hopes before they had even really begun. Hooper, Ruth, Schang, Joe Bush, and Everett Scott had hired a car to take them from the race track back to the Hotel Marion. The driver tried to let them off short of the hotel, demanding payment, so he could run back to the track and pick up another fare. The Sox quintet called a policeman who ordered the driver to continue on to the hotel. The enraged driver shouted, “I will tip you all out first” and then tore off at such speed that he “banged a jitney aside, knocked a horse down and busted up a wagon.” Hooper’s threat regarding the chauffeur’s nose brought an end to the affair. [Boston Globe, March 21, 1918]

After the March 17 opener, the two teams didn’t play another game for a week. Nevertheless, despite being a war-shortened season, the number of exhibition games was not diminished. The spring season comprised 14 games, more than any year since 1911. (During the season, they added three more. None of them were fundraisers for the war effort; this became widespread practice during the Second World War. The Red Sox hadn’t played postseason games since 1910, though some of the players toured after the World Series – and paid a stiff price for doing so.)

The weather failed to cooperate. Several players developed colds, and there were almost no intrasquad scrimmages. The Sox and Dodgers finally got in another game on the 24th, and Babe Ruth hit a grand slam home run as part of a six-run third inning that sank the Trolley Dodgers, 7-1. Mays and Ruth pitched; both Ruth and Dutch Leonard played right field. With two outs and the bases loaded in the third, Ruth swung at the first pitch and the ball “cleared the fence by about 200 feet and dropped in the pond by the alligator farm.” In Little Rock, the second-string Boston Yannigans clobbered the Brooklyn Rookies, 18-8.

The following day, too many players were under the weather, so Barrow had the men work on signals, leads off first base, sacrifice bunts, and a number of fundamentals. Too many lame arms among the pitchers resulted in the following day being one devoted to batting practice.

On March 27, the two teams matched off for two games in Little Rock. The games were held at Fort Pike; the first was played in front of 700 or 800 soldiers who saw the Brooklyn regulars beat the Red Sox, 3-2. The Post‘s Paul Shannon noted several situations where Red Sox players didn’t seem to have their heads in the game, and lost opportunities as a result. Thomas was charged with two errors. The Red Sox regulars beat the “Agnews” the following day, 2-1. Prospect Lona Jaynes threw a complete game three-hitter for the Regulars and Dick McCabe allowed the first stringers only six hits.

On March 29, the Red Sox learned that Majestic Park would be demolished later in the year so that railroad tracks could be laid through the property. The Sox signed a five-year option on Fordyce Park in Hot Springs as their new spring home, but it was a revocable deal and Frazee commented that he might move the team to another location, one that did not have a racetrack. He felt the ballplayers sometimes seemed a little too ready to end practice early and head out to the track.

Sam Jones arrived in camp at this point; the Red Sox had thought he was due to be inducted at Camp Sherman, and had placed him on voluntary leave, but he had instead been placed in Class B and was hurriedly offered a 1918 contract. Frazee said he might seek an extra infielder but otherwise believed he had the men he needed.

On March 30, the Red Sox beat the Dodgers at Little Rock, 4-3, scoring twice in the eighth and twice in the ninth – on Ruth’s home run. It was his fourth home run in four games against Brooklyn.

On the last day of March, the Red Sox again won the game in the ninth inning, scoring five times to come from behind and take the honors, 7-4. On the first day of April, the Sox did it yet again, scoring the run that broke a 2-2 tie with one out in the bottom of the ninth. Strunk walked, stole second, took third on McInnis’s sacrifice. After Hoblitzell was walked intentionally, Whiteman singled Strunk in with the game-winner.

The two teams traveled to Texas and played their first game on April 2, a dramatic 16-inning affair in Dallas that began with the Red Sox scoring four times in the top of the first. Tied 4-4 after nine, both teams scored twice in the 15th, the tilt going in Boston’s favor in the 16th when newly-arrived Dave Shean doubled and then took third on a bad pickoff peg. He scored on Strunk’s sacrifice fly for a 7-6 Boston victory. Ruth was so angry at striking out his first time up that he flung his bat “half way to right field” and then batted right-handed his second time up (he whiffed again). The teams traveled to Waco on April 3 and the Dodgers won 2-1, but not without some ninth-inning suspense, as Shean, the potential tying run, was stranded at second to end the game.

And for the third game in a row, Shean shone. Playing in Austin at the University of Texas (most of the crowd being military aviation students), Boston beat Brooklyn, 10-4. Shean had himself a 5-for-5 day. Harry Hooper had three hits, including a triple and a home run. Boston lost in Houston on the 5th, 5-3, with two McInnis errors proving very costly. Shean drove in two runs. It might have been spring training, but the Boston Herald reported that the Sox manager gave the men a “merciless tongue-lashing…a full hour of the ruthless criticism that big Ed Barrow knows how to hand out.”

The two teams squared off for 13 innings in New Orleans on April 7. Some 5,000 fans saw the Dodgers’ Jim Hickman triple, then score on Clarence Mitchell’s single for a 4-3 Brooklyn win. Moving on to Mobile, the teams played 13 innings again, but this time darkness brought an end to a game knotted 6-6. Each team scored once in the 14th frame. Playing the following day in Birmingham, the temperature dropped 50 degrees and Brooklyn beat Boston, 3-1, the game called after seven innings due to darkness.

There was an odd twist on the two Alabama dates in that men from both teams joined together to play as the “Supersox” (derived by combining the old Brooklyn Superbas name with the Red Sox) for a couple of extra games. On April 7, the “Brooklyn-Boston” team (as it was shown in box scores) played the Southern Association team at Mobile and suffered a 2-0 one-hit shutout. The combined team was composed of “second team” players, by and large. On April 9, at Birmingham, the Barons beat the combined team by, again, a score of 2-0 in another “Supersox” game. The regular game was played in frigid conditions and both teams rushed through the work, completing the entire seven-inning game in 35 minutes.

The game scheduled for Chattanooga on April 10 was called off due to cold weather after both teams arrived at the ballpark. Several of the players visited a nearby internment camp for German prisoners of war. Earlier hopes to play in Louisville and Pittsburgh, or Richmond, on the way north had come to naught. That evening, the Red Sox took the 10:30 train out of town and headed for Boston with a three-hour layover in Cincinnati. The Red Sox had won the series of games, 8-5, with one tie. There was also the game the Red Sox second team crushed Brooklyn’s Yannigans. Scott, Strunk, and Hoblitzell were all hobbled with foot and ankle injuries and, in general, as Paul Shannon wrote in the Post, “The Red Sox did not put up the brand of ball toward the end of the series that they did at first. There is a lot of room for improvement in their work.”

The team arrived home on April 12. Groundskeeper Jerome Kelley was to have had Fenway ready for an afternoon workout on Saturday the 13th, but the city was blanketed with snow. Those who boarded at Put’s (a hotel where many players dwelled) checked in there; the others made their way to their various apartments/abodes.

Coach Hugh Duffy arranged for the use of the Harvard cage – the first time major leaguers had worked out there – and after four days of inactivity the ballplayers “raced around the cage like a lot of colts let out to pasture.” [Boston Herald] Harry Frazee told the Herald, “You can say that I am well pleased with the club’s prospects for the coming season.”

The Boston Post‘s Paul Shannon wrote a long piece the day before the season opened, headlined “Red Sox Feel All Set to Go After Another World’s Title This Season.” He began the article, “Barring the absence of a strong utility string, hitherto one of the traditional features of a Boston Red Sox team, the newly constructed American League outfit, an organization that hovered on the verge of disruption only to be rebuilt with marvelous rapidity will take the field…Monday.”

The war had taken many, Carrigan was no longer manager, others had been traded away…all told, it was “practically a new team.” Shannon gave new manager Barrow credit for having “moulded a team well worthy of supporting Red Sox tradition and repeating Red Sox triumphs.”

And triumph was, of course, the tradition for the Boston Americans who had won the pennant in five of the preceding 15 years. Credit must go, of course, to Harry Frazee, who hired Barrow and funded the acquisitions that seemed to Shannon to set the team up for a strong season. Frazee was not an absentee owner but, despite his other responsibilities in the theater world, an engaged and energetic owner.

Shannon detailed the various positions. Even at this late date, two players that he expected to make strong contributions never did: Johnny Evers and Paul Smith. But all in all he saw “an array of congenial, hard-working players with confidence in their own ability and supreme confidence in the judgment and ability of their new manager. A brainy, well-behaved set of players who will pull hard for victory all the time, because they see the vision of another pennant and regard their amalgamation that union of veterans with newly purchased stars as a remodeling, which may assure them of first honors for more than one year. No jealousy mars their good fellowship and harmony is the keynote of this crowd. Small wonder that Barrow is contented.”

No team can go through an entire season in harmony, however, but the Red Sox did begin the 1918 season on April 15 with a 7-1 win over the Philadelphia Athletics.

BILL NOWLIN is national Vice President of SABR and the author of nearly 20 Red Sox-related books. Bill is also co-founder of Rounder Records of Massachusetts. He’s traveled to more than 100 countries, but says there’s no place like Fenway Park.

Notes

1 Burt Whitman, “Boston Clubs Look Like New,” Boston Herald, March 3, 1918: 17.